// By Kat Braz (LA’01, MS LA’19)

// Photos by Charles Jischke (MBA’08)

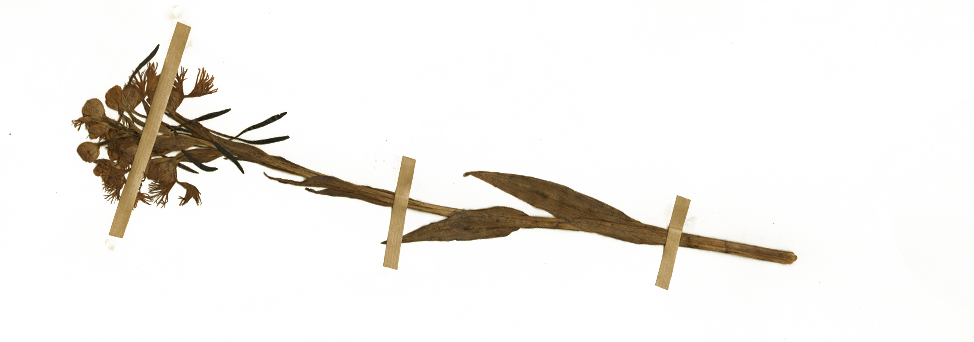

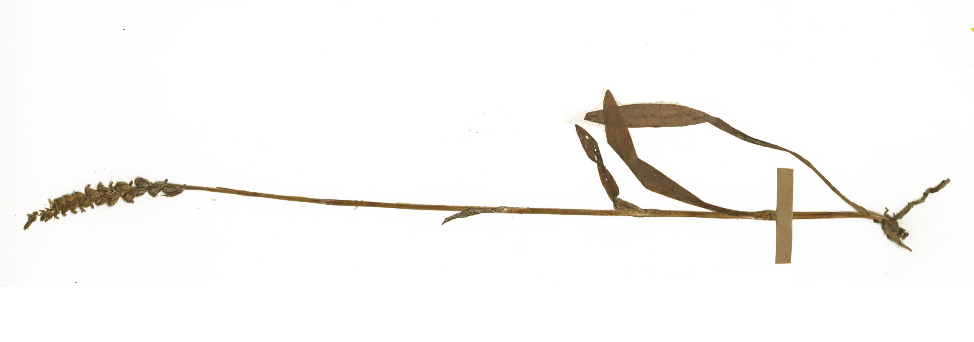

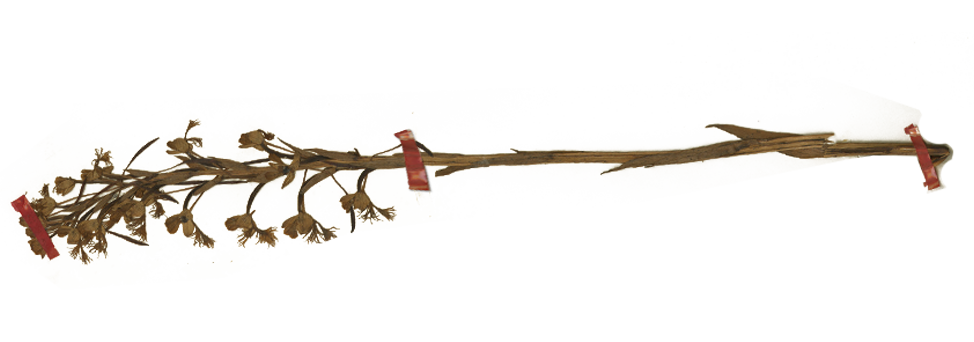

The earliest herbarium—a collection of plant samples preserved for scientific study—dates to 16th-century Italy, when the Bologna physician and botanist Luca Ghini (1490–1556) sought to make plant material available to his students in winter when the plants were dead or dormant.

The specimens were flattened between two pieces of paper to remove moisture. Once dried, they were mounted on paper sheets with notations on the plant’s name, where the plant was gathered, and any distinctive features. The pages were bound into volumes to enable transport from one location to another, thus making plant material from faraway places available indefinitely.

The Purdue Herbaria

Purdue’s herbaria began with Rev. John Hussey, a Union army chaplain who joined the university faculty in 1874 as the first professor of botany and horticulture. Disabled by sudden paralysis in 1880, Hussey retired from the university. Two years later, the Board of Trustees paid his wife $50 compensation “for botanical specimens furnished to the university.” At that time, the collection numbered 2,700 specimens.

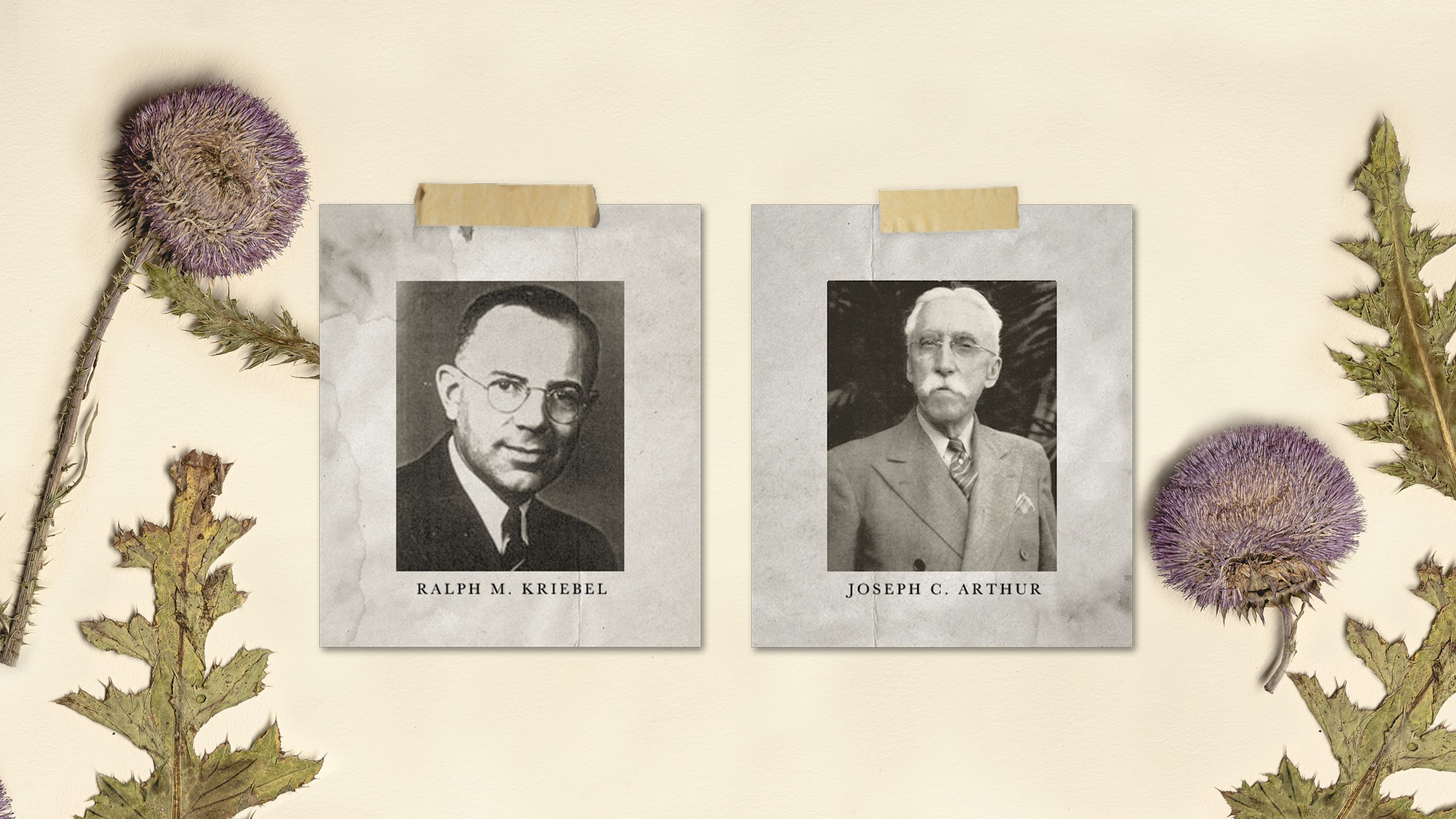

Hussey’s surviving specimens are now part of the Ralph M. Kriebel Herbarium, a collection of more than 110,000 specimens of fungi, vascular plants, algae, and bryophytes housed in the Lilly Hall of Life Sciences and maintained within the College of Agriculture’s Department of Botany and Plant Pathology.

Kriebel’s passion for plant collection was encouraged by Charles Deam, Indiana’s first forester. The two began corresponding in 1932, and Deam became Kriebel’s mentor, field companion, and friend. Kriebel joined the university as an extension soil conservation specialist in 1943. By the time of his death in 1946, he’d amassed one of the largest personal collections of Indiana plants, second only to Deam.

Kriebel’s mother sold his collection of 10,866 mounted specimens to the university for 10 cents a specimen, and most of Purdue’s existing herbaria were combined and dedicated as the Kriebel Herbarium in 1961.

The companion herbarium, the Joseph C. Arthur Fungarium, is thought to be the world’s most important collection of plant rust fungi, or rusts. Rust species are some of the most harmful pathogens to agriculture, horticulture, forestry, and natural ecosystems. The Arthur Fungarium boasts more than 125,000 specimens of more than 5,000 rust species.

Arthur (HDR S’31), whose fascination with plants stemmed to his boyhood in rural Iowa, came to Purdue in 1887 as the professor of botany and first head of the department. Described by his successor George B. Cummins (PhD A’35, HDR A’81) as “a man of small stature but large presence,” Arthur was a pioneering mycologist—someone who works with fungi. His groundbreaking research included working out the life cycles for hundreds of agriculturally important rusts, leading to the successful breeding of varieties of cereal grain resistant to rust diseases.

“Arthur was a very big deal in his field,” says Rabern Simmons, curator of fungi for the Purdue Herbaria. “He began his personal collection in 1882, and during his 19 years at the university, he conducted more than 3,000 experiments. He also published the Manual of the Rusts in United States and Canada in 1934, which is still indispensable for rust fungal specialists today.”

Controversy Over the Collection

When Arthur started at Purdue and brought his personal herbarium with him, he initially received no support from the university to purchase the supplies necessary to maintain and expand the collection, funding the project with his own money.

In 1906, Congress passed the Adams Act, providing supplemental funding to state agricultural experiment stations to support scientific research. With official recognition and support, Arthur’s rust project flourished. During his tenure at Purdue, Arthur accumulated more than 40,000 rust specimens in the herbarium he established at the university’s agricultural research station. Although he retired from Purdue in 1915, Arthur still regarded the collection as his property, having largely spent his own money to finance it.

“One day, I was called into the director’s office and questioned about the work in the herbarium,” Arthur recounted. “I was informed, much to my surprise and chagrin, that the herbarium was considered property of the station.…This seemed to me unjust, and a poor return for the years of labor I had put into building up the collection.”

On July 4, 1918, Arthur arranged for movers to descend on campus in the middle of the night to remove his entire collection of rusts, cases, drawings, and manuscripts and relocate everything to his home in Lafayette.

On July 19, the university requested that Arthur return “the rust herbarium collected, classified, and maintained by the university at great expense from the Adams Fund.” Arthur refused. President Winthrop Stone called for the Board of Trustees to convene on July 24 to discuss the matter. The minutes from the meeting state that “this Board strongly disapproves of the actions of Dr. J. C. Arthur” and empowered university officials to take any legal steps necessary to recover possession of the property.

“The university reached an agreement with Arthur the following month,” Simmons says. “However, he had some stipulations for returning the collection. Among them, he wanted to retain access to the university’s research facilities and resources to continue his work. He wanted compensation, and the university agreed to pay him $1,000 to buy back the collection, which worked out to about 3.5 cents per specimen at the time. And he insisted his collection be kept separate from the other collections on campus. He didn’t want his name to be lost to history and his collection shuffled around to become part of the larger university herbarium.”

At the time of Arthur’s death in 1942 at age 92, the Arthur Herbarium held 60,000 specimens. An obituary read before the faculty of the university noted Arthur “was a scientist of unusual ability and his contributions in the field of botany were numerous and of uniform excellence.”

The collection was later renamed the Arthur Fungarium and continues to honor his wishes by including only rust fungi. All other fungi specimens are cataloged in the Kriebel Herbarium.

Revitalization of the Herbaria

When Cathie Aime, professor of mycology, was appointed as director of the Purdue Herbaria in 2012, the position had been vacant for more than 20 years. Aime is the only scientist in the United States—and one of few in the world—who studies the systematics of rust fungi. She’s also the 2023–24 president of the Mycological Society of America. The significance of Purdue’s herbaria lured her from Louisiana State University.

“The Arthur Fungarium has the largest collection of rust type specimens in the world,” Aime says. “A type is the physical specimen that carries the name of the species. Scientists compare specimens against the type to confirm the identity of the species, and we have more than 3,000 types of the 8,000 described species. It’s an incredibly valuable resource. Researchers from all over the world send us specimens to identify using our reference material so they can figure out what’s going on with their crops in Ethiopia or Zimbabwe or Australia or Germany.”

Simmons was hired in 2022 to manage the day-to-day operations of the herbaria, which now has an updated website that describes the collections and details their histories. He’s also continuing efforts to digitize the entire collection and has stepped up outreach efforts.

Plant sciences major Julia Peterson looks for a specimen in the Purdue Herbaria cabinets. She’s an undergraduate researcher in the Aime Lab, working with Jeffery Stallman, a graduate research assistant in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, to conduct genetic sequencing on fungi found in Indiana state parks.

Jaein Choi is a PhD student working in the lab of Daniel Park, assistant professor in the Department of Biological Sciences. Choi conducts research in the Kriebel Herbarium weekly, studying the complex defense mechanisms across the cardueae tribe of thistles.

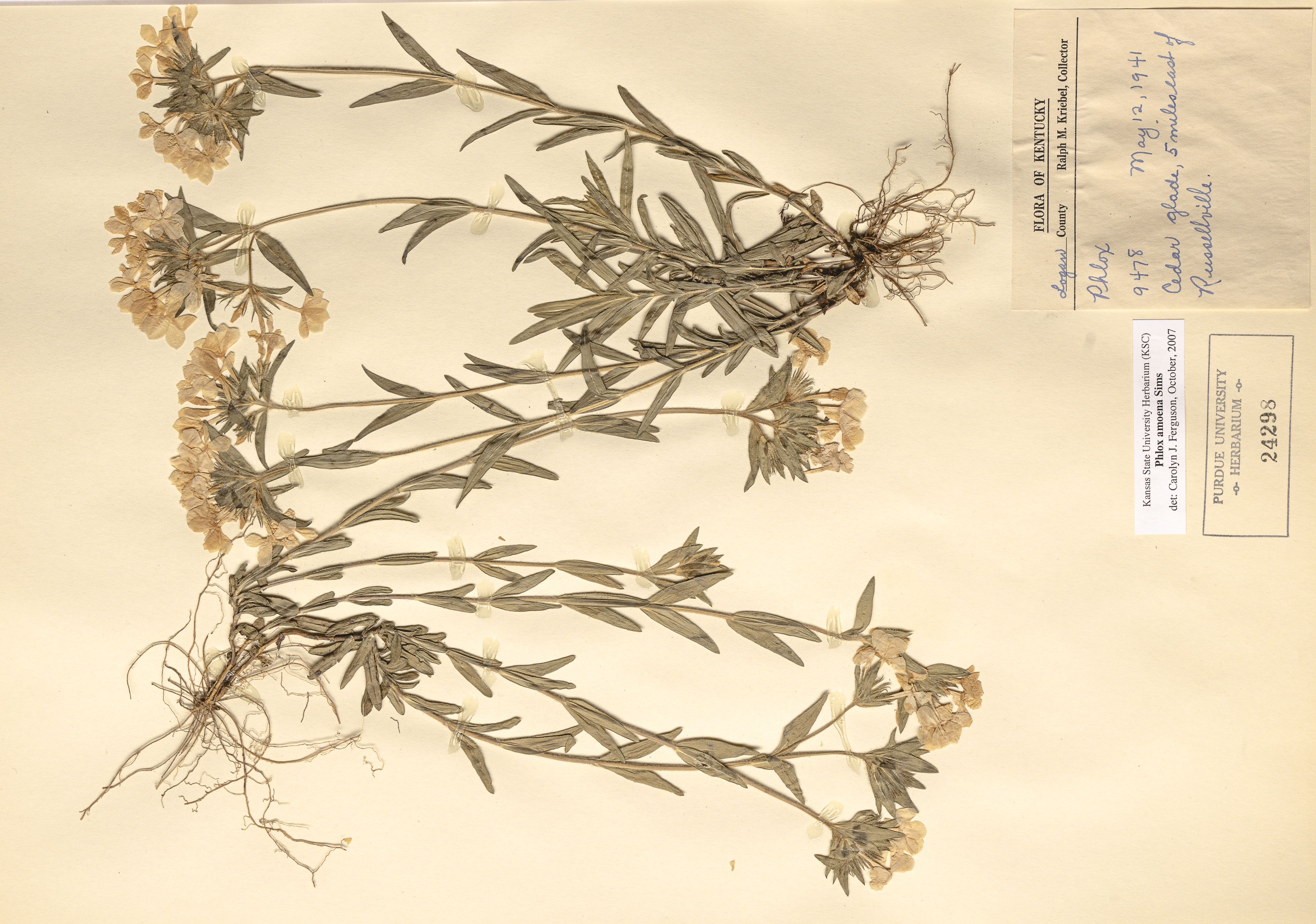

Both the Kriebel Herbarium and the Arthur Fungarium contain specimens dating from the 1800s to the present. Researchers rely on these specimens not only to identify species but also to access rare or extinct species, conduct DNA analysis and sequencing, and gain a better understanding of how the ecology of an area has changed over time.

“Because each plant specimen includes documentation about when and where it was collected, herbaria chronicle the historic environment,” Simmons says. “This is particularly important when researching topics like climate change or evolving agricultural needs. There are materials collected by Ralph Kriebel from terrains and habitats that no longer exist in the state of Indiana. Without herbaria, we’d just be making assumptions about the past. These collections provide concrete information from which you can build hypotheses for interdisciplinary study.”

With its rich history of botanists and mycologists, Purdue was long known as a preeminent institution for organismal biology—the study of structure, function, and evolution of an organism—particularly in the field of rust fungi. There are fewer organismal biologists in the U.S. now than there were in the early to mid-1900s. Aime wants to reverse that trend.

“With modern threats of climate change, global biodiversity loss, anthropogenic factors, and increased disease spread among both plants and animals, we need people who are trained in organismal biology,” Aime says. “These biologists can model and predict outcomes of the new situations we’ve created. At the same time, we’ve allowed that expertise to erode in the United States. My vision is to make Purdue, once again, the premier place for the study of agricultural pathogens like it used to be 100 years ago.”

Important Specimens in

the Arthur Fungarium

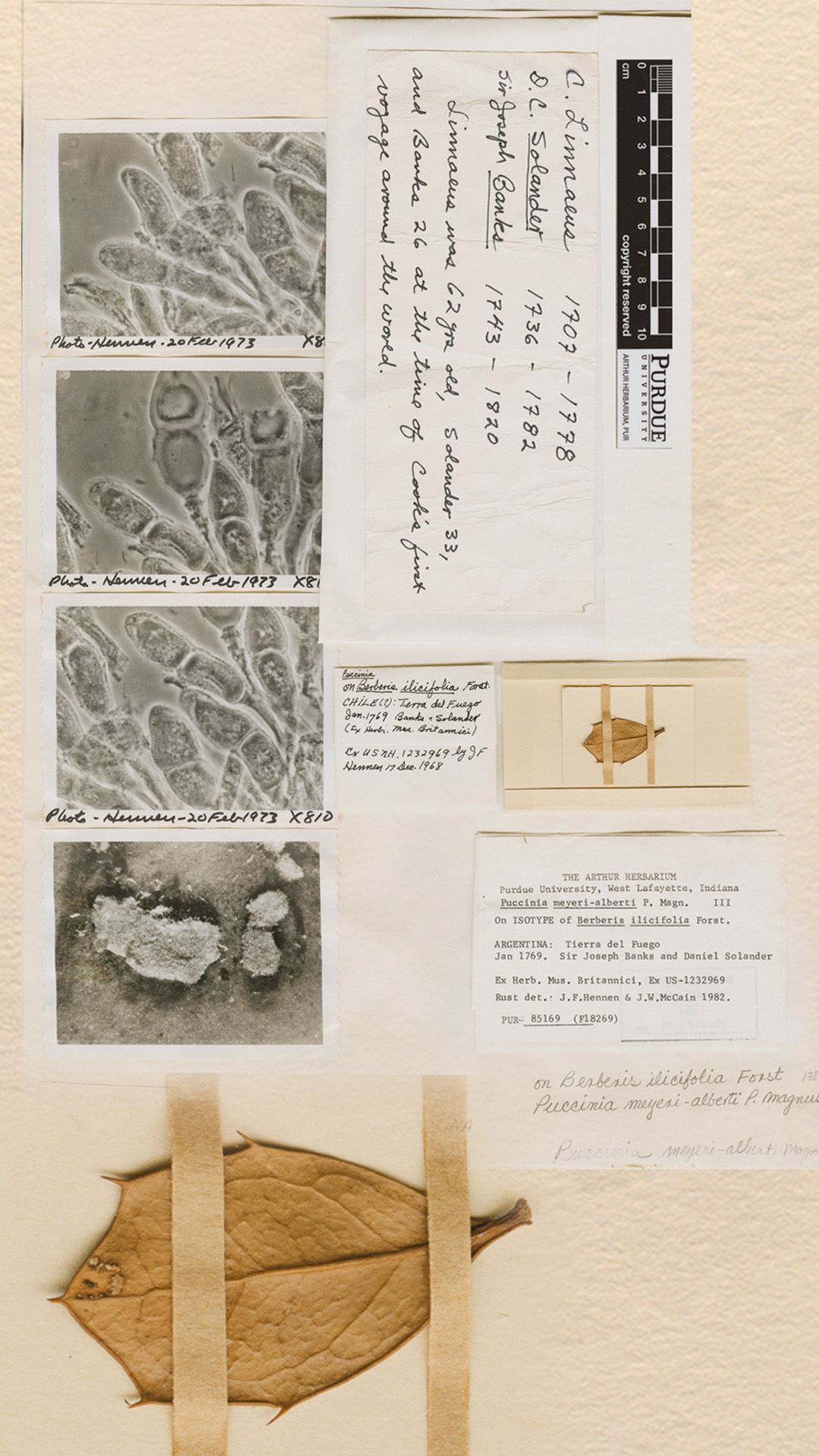

A Voyage With Captain Cook // The oldest fungal specimen in the United States is housed at Purdue. It is a rust fungus that was collected in 1769 in Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America during the first voyage of Captain James Cook’s ship the HMS Endeavour.

The holly barberry leaf was collected during a treacherous expedition, with the party trapped overnight in a mountainside blizzard.

In the early 1970s, the sample was sent to Joseph F. Hennen (PhD A’54), then director of the Arthur Fungarium and a noted expert in rust fungi, who determined the specimen had been infected with a rust fungus, Puccinia meyeri-alberti, at the time of its collection 200 years before.

A Nobel Laureate // Nobel Peace Prize laureate Norman Borlaug worked throughout his life to feed a hungry world. During the 1940s and ’50s, Borlaug helped transform agricultural production in Mexico. Some of his historic rust collections are now housed in the Arthur Fungarium.

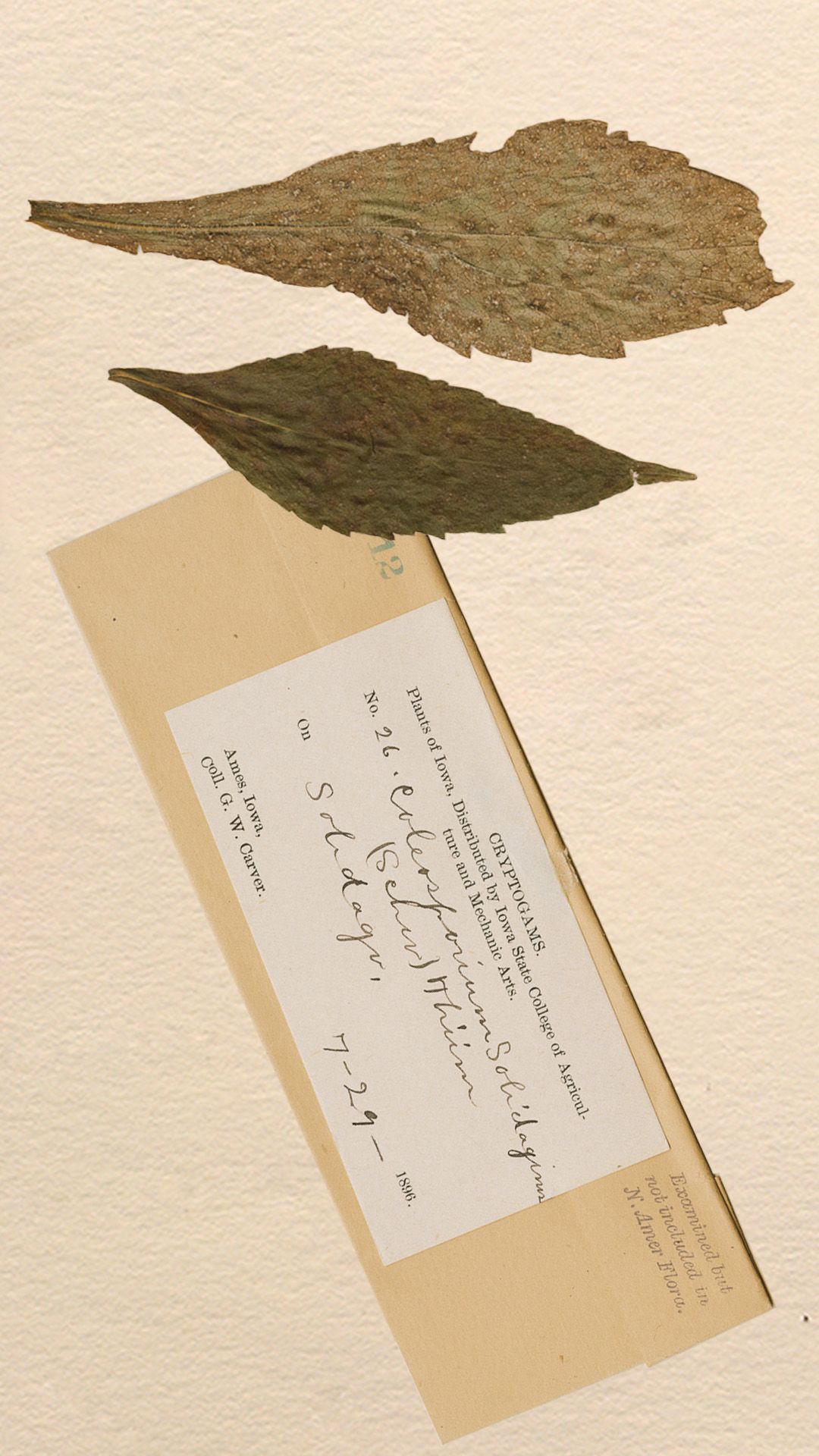

A Prominent African American Botanist and Inventor // George Washington Carver is renowned for his research into and promotion of alternative crops to cotton, such as peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. The Arthur Fungarium holds more than 70 rust specimens collected by Carver—primarily from Ames, Iowa, and Tuskegee, Alabama—from 1892 to 1935.

A Voyage With Captain Cook // The oldest fungal specimen in the United States is housed at Purdue. It is a rust fungus that was collected in 1769 in Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America during the first voyage of Captain James Cook’s ship the HMS Endeavour.

The holly barberry leaf was collected during a treacherous expedition, with the party trapped overnight in a mountainside blizzard.

In the early 1970s, the sample was sent to Joseph F. Hennen (PhD A’54), then director of the Arthur Fungarium and a noted expert in rust fungi, who determined the specimen had been infected with a rust fungus, Puccinia meyeri-alberti, at the time of its collection 200 years before.

A Prominent African American Botanist and Inventor // George Washington Carver is renowned for his research into and promotion of alternative crops to cotton, such as peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes. The Arthur Fungarium holds more than 70 rust specimens collected by Carver—primarily from Ames, Iowa, and Tuskegee, Alabama—from 1892 to 1935.

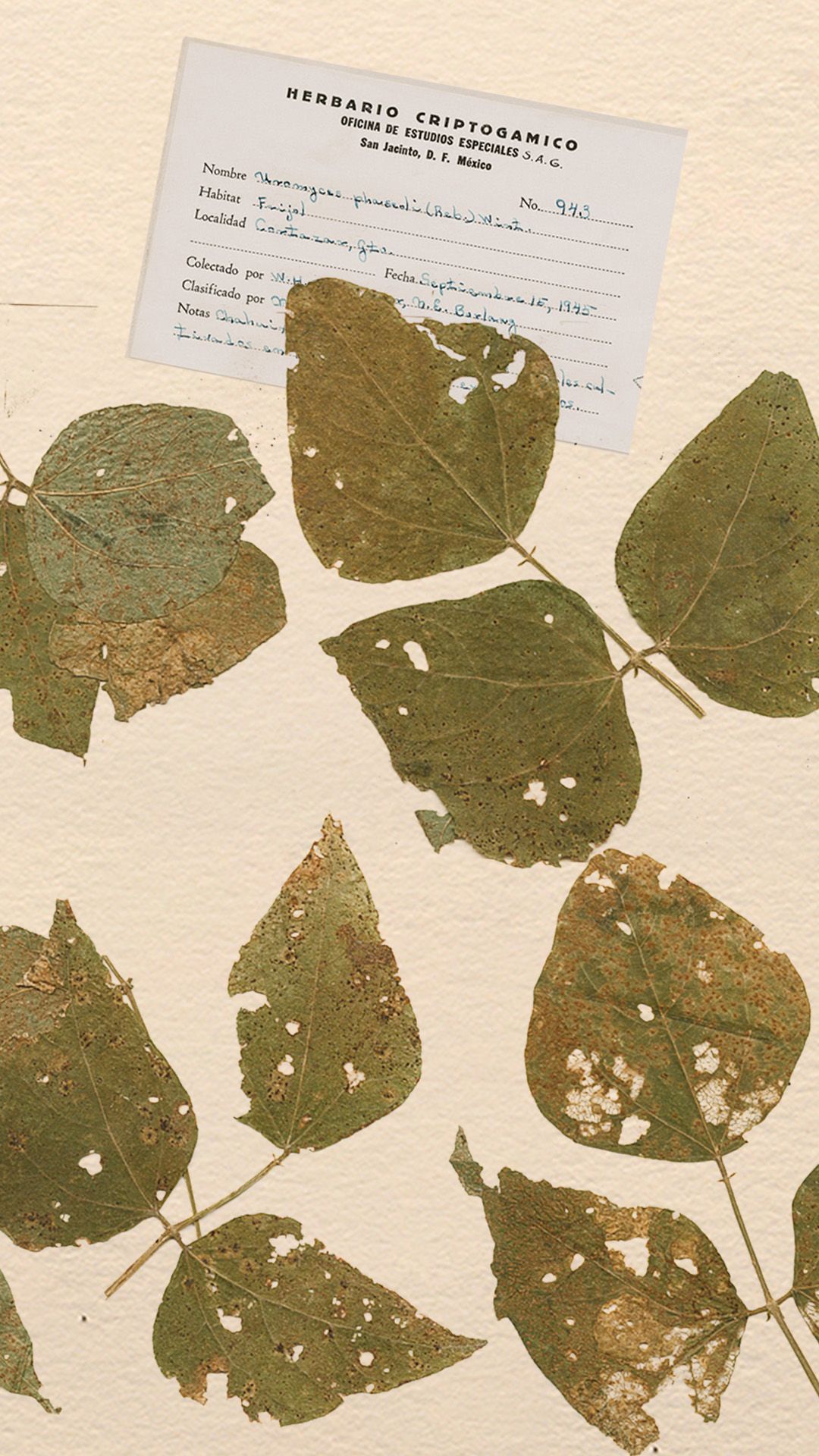

A Nobel Laureate // Nobel Peace Prize laureate Norman Borlaug worked throughout his life to feed a hungry world. During the 1940s and ’50s, Borlaug helped transform agricultural production in Mexico. Some of his historic rust collections are now housed in the Arthur Fungarium.

What’s In a Name?

“The naming of species, especially for plants and fungi, is always shifting,” Simmons says. “It’s very easy to see a mushroom on the ground and say, ‘I’ve seen something that looks like that before. I’m pretty sure that it’s species A’—but there’s hidden biodiversity within fungi in particular. Our investigative tools have improved over time, especially with molecular and genomic studies. A lot of fungi traits have undergone convergent morphological evolution, so while they look very similar, they may actually be in completely different genera, families, or orders, depending on their molecular characteristics and how we interpret those now.”

For his graduate studies work in botany and plant pathology at the University of Maine, Simmons described an entirely new order of fungi based on a handful of species that had previously been classified in another order. After examination of ultra-structural microscopic characteristics and using molecular techniques, it was determined they deserved to be classified in their own order.

“That kind of reshuffling of fungi is pretty common,” Simmons says. “Within the Mycological Society of America, it’s a joke that if a scientist identifies a new species of primate, the story will be on the cover of Nature. It’s big news. When a mycologist discovers a new fungus, that’s a Tuesday.”