Call of the Wild:

Save Wolves,

Save Wilderness

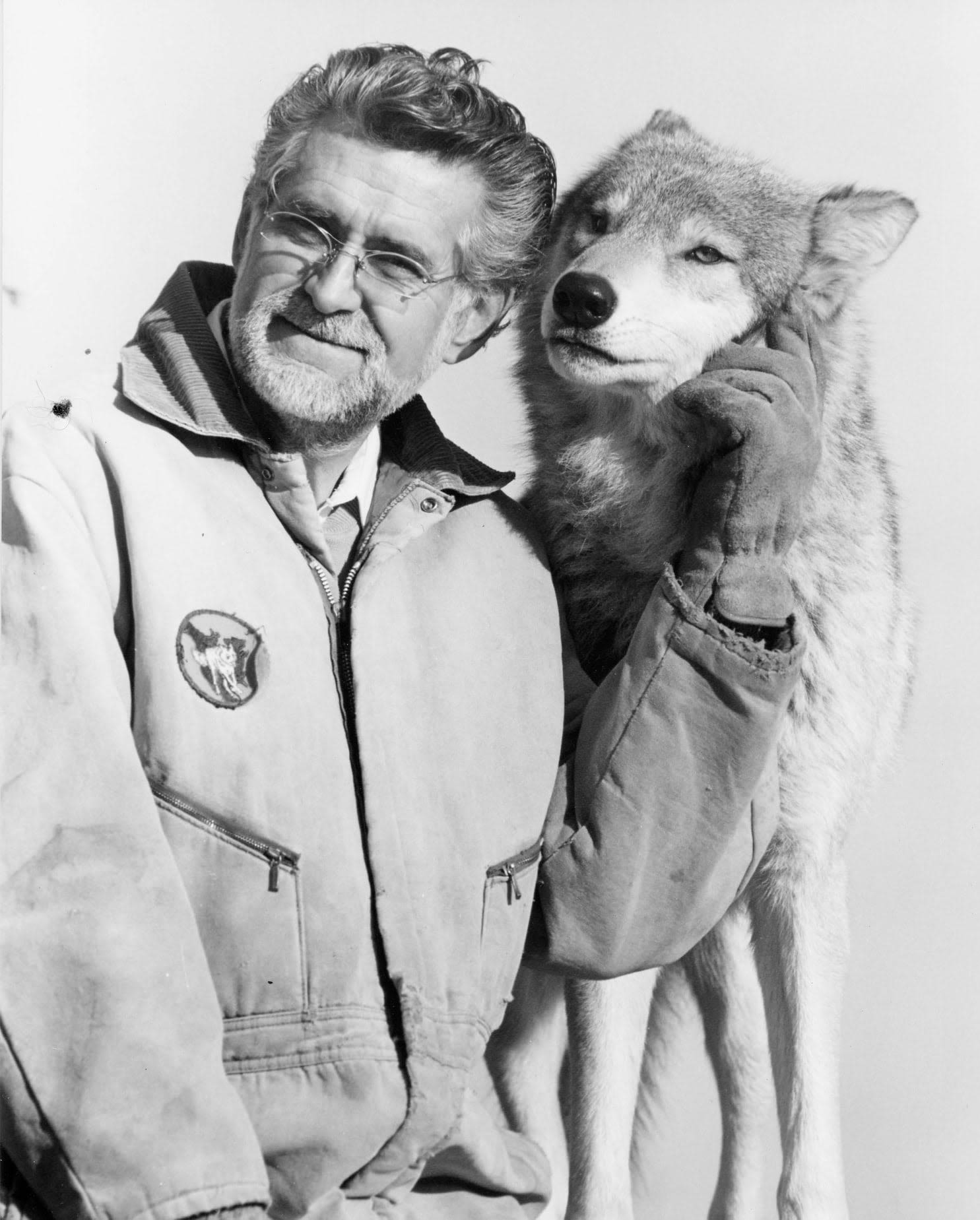

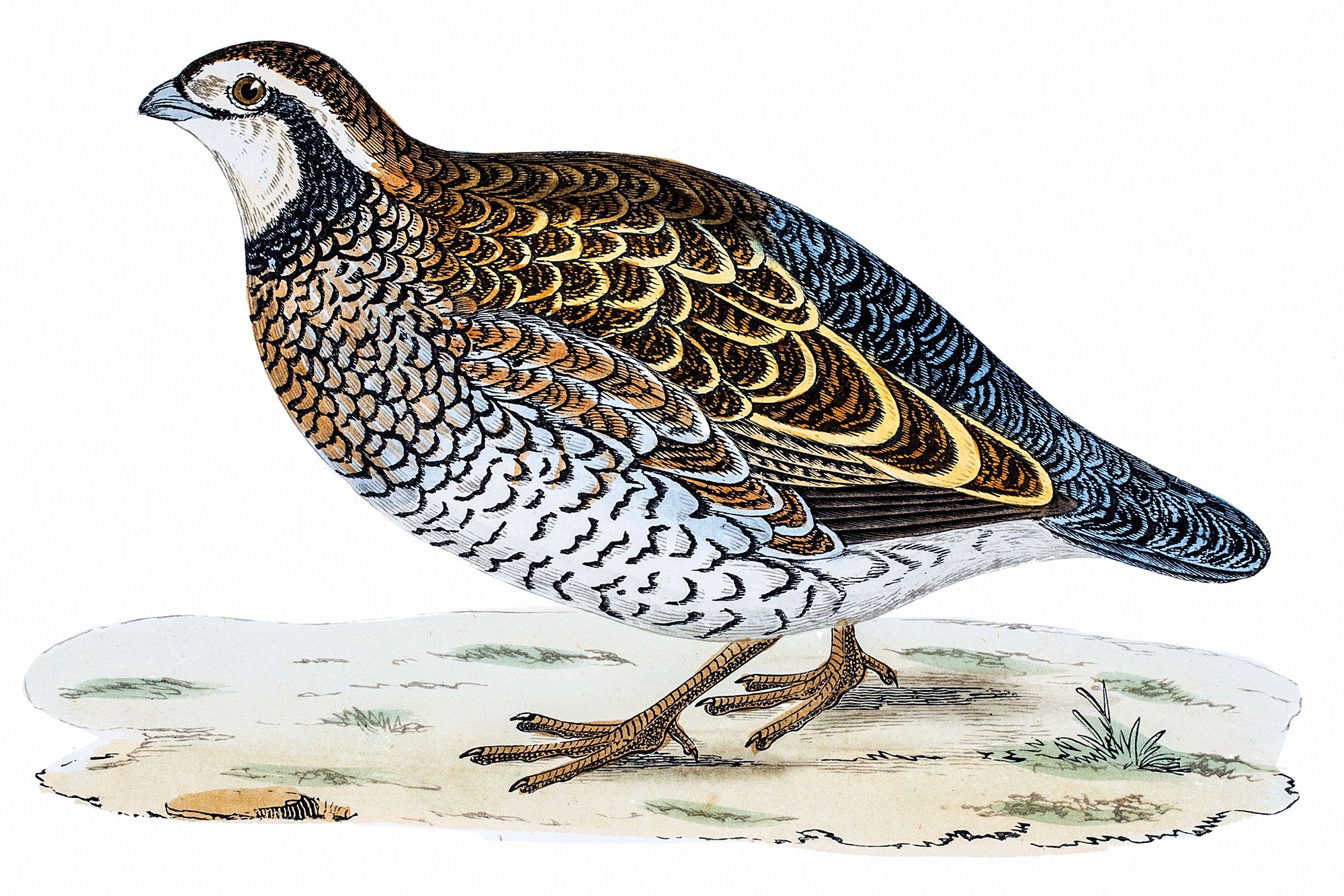

Founded by Purdue ethologist Erich Klinghammer in 1972, Wolf Park began as an experiment to study wolf behavior. The pioneering research conducted there over the past 50 years contributed to a better understanding of the apex predator and facilitated its reintroduction into the wild.

Call of the Wild:

Save Wolves,

Save Wilderness

Founded by Purdue ethologist Erich Klinghammer in 1972, Wolf Park began as an experiment to study wolf behavior. The pioneering research conducted there over the past 50 years contributed to a better understanding of the apex predator and facilitated its reintroduction into the wild.

// By Kat Braz (LA’01, MS LA’19)

// Photos and video courtesy of Wolf Park

Erich Klinghammer

Erich Klinghammer

A lifelong fascination with wolves led Pat Goodmann (MS HHS’78) to Purdue University to study under Erich Klinghammer, a professor of ethology—the study of animal behavior.

Erich Klinghammer

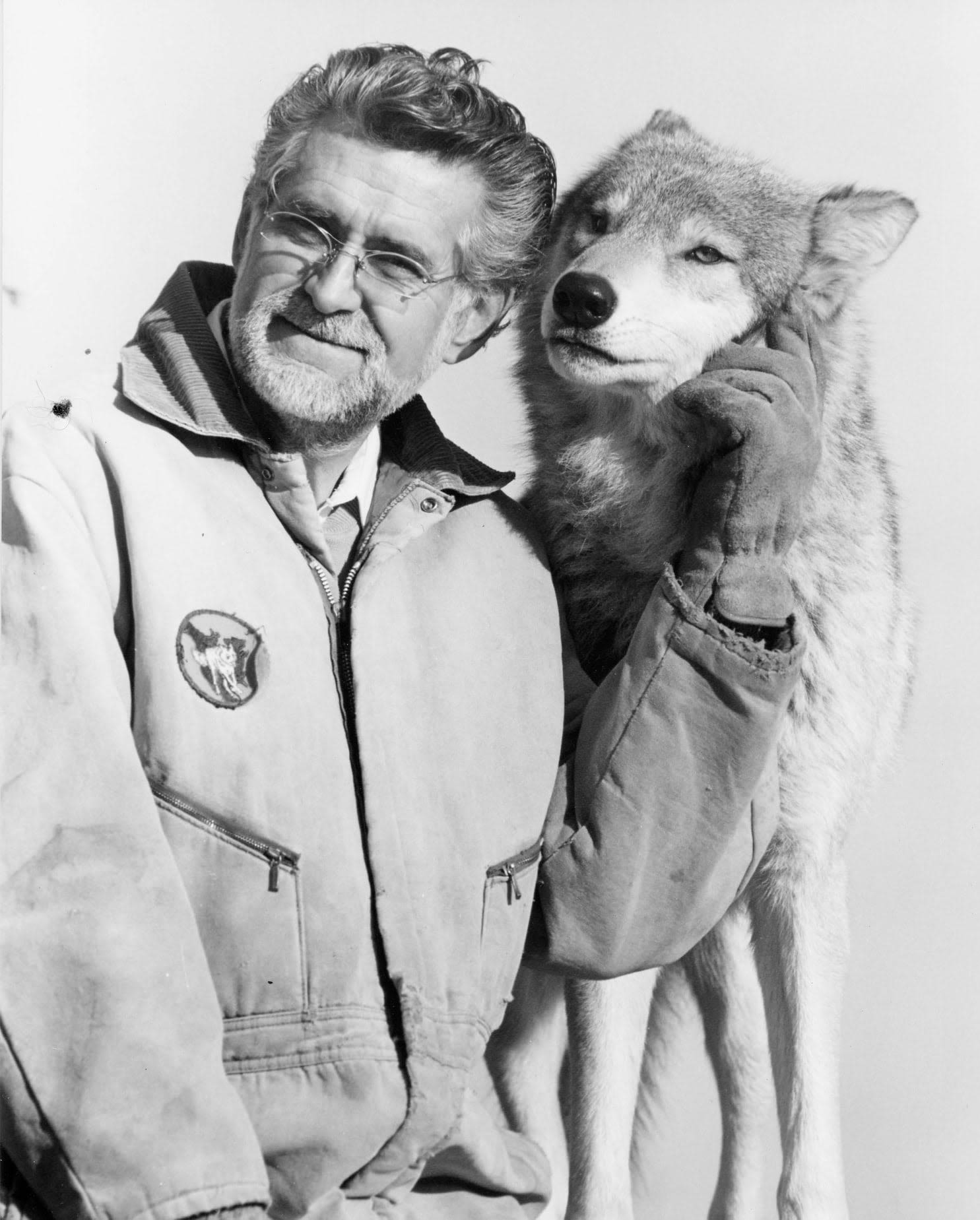

Wolf Park, the wildlife conservatory Klinghammer established on his farm outside of Battle Ground, Indiana, celebrates its 50th anniversary this year. Goodmann, who arrived at the park in 1974, remains on staff as head animal curator emerita.

“My father saw an article in our local paper about this Purdue professor who wanted to start a wild animal park,” Goodmann says. “I came down to Purdue and met Dr. Klinghammer, and I always knew from the beginning that I wanted to stay at the park as long as possible and help build it.”

Pioneering Research

A graduate of the University of Chicago, Klinghammer began studying the imprinting of birds there. He transferred to Purdue’s Department of Psychology in 1968, and after realizing he had a severe bird allergy, he switched his focus to gray wolves. In 1972, he received a pair of wolves, siblings Cassie and Koko, from the Brookfield Zoo and began his pioneering study on wolf pack dynamics and social behavior, including early analyses of wolf howls. He continued to add to his pack with captive wolves from other zoos and facilities, and in 1977, the first litter was born at Wolf Park.

Klinghammer wanted to observe wolves’ interactions to learn about their behavior and communication. Once a fixture across North America, the native gray wolf population dwindled to fewer than 1,000 in the Upper Midwest by 1967. That year, they were first listed as endangered by the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966. They became legally protected in 1974 by the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

“There wasn’t a lot known about wolf behavior at the time,” says Karah Rawlings (LA’99), executive director of Wolf Park. “Human intervention had nearly eradicated wolves across the country. They’re a naturally elusive species and tend to avoid humans, which are their biggest predator. So it was very difficult to observe wolves in the wild and monitor their behavior.”

In order to conduct his research, Klinghammer sought to socialize wolves so they’d be comfortable around humans rather than domesticate them like pets. The wolves would live in large enclosures that replicated their natural environment.

“Erich believed that the way to know the animals really well was to be involved in all aspects of their care. The more time you spend around the animals, the more likely you will see interesting or unusual things.”

Klinghammer and Goodmann documented their findings in a wolf ethogram, a wolf-to-human dictionary of behaviors used by wolf researchers around the country.

“The ethogram is a catalog of body language, facial expressions, vocalizations, and more complex behaviors built from those simple building blocks,” Goodmann says. “It gives people studying the same species a common language to discuss what they observe.”

Purdue’s Pedigree

Three of the most influential wolf biologists in the world have connections with Purdue and Wolf Park.

DOUG SMITH

Doug Smith, senior wildlife biologist at Yellowstone National Park, led the Yellowstone Wolf Project, reintroducing the apex predator to the park where it had been eradicated by the 1920s. Begun in 1995, the multi-decade recovery effort marked the first deliberate attempt to return a top-level carnivore to a large ecosystem. More than 25 years later, it is considered one of the most successful wildlife conservation projects in the world. Smith interned at Wolf Park and helped raise a litter of pups in 1979.

ROLF PETERSON

Rolf Peterson (PhD A’74), internationally recognized wildlife expert, came to Purdue to study under Durward Allen (HDR A’85), professor of forestry and natural resources. After earning his doctorate, Peterson took over the Isle Royale Wolf and Moose Research Project from Allen and served as its lead researcher for more than four decades. Established in 1958 as a 10-year study, the Isle Royale project is now the longest continuous study of any predator-prey system in the world. Klinghammer served on Peterson’s dissertation committee and taught him how to conduct behavioral research.

DAVID MECH

David Mech (PhD A’62, HDR A’05) was Allen’s first graduate student and helped launch the Isle Royale project where Smith came to study after his time at Wolf Park. Considered the foremost international authority on the ecology of wolves, Mech has tracked and studied wolves near Ely, Minnesota, as a senior research scientist for the U.S. Geological Survey since 1966. In 1993, he founded the International Wolf Center in Ely, which maintains a live wolf exhibit and is dedicated to advancing the survival of wolf populations.

“Since humans first drew petroglyphs to record their observations, wolves have populated the art, literature, and culture of our planet. The howl of the wolf sends shivers of fascination and love—or fear and distrust— up the backs of people around the world. Hardly anyone treats the wolf with indifference.”

—International Wolf Center // Ely, Minnesota

Klinghammer’s Legacy

As a high school senior desperate for practical experience working with wolves, Smith wrote to five well-known wolf biologists asking if he could come and observe their research. Klinghammer was the only one to write back.

“To this day, I have a soft spot in my heart because I get two or three high school or college kids every year wanting to do the same thing,” Smith told the National Park Service. “I can’t bring myself to say no because one of those five wrote me back. It’s been a love of my life to study them. I am tirelessly still loving it.”

When Smith arrived at Wolf Park in 1979, there were no wild wolves out West.

“Erich’s research defined the baseline for wolf behavior,” Smith said. “Even though his wolves lived their entire lives in captivity, there are a lot of similarities to wolves in the wild.”

Klinghammer envisioned a wolf nature park in every state, Goodmann says.

“He was dedicated to his research but also to conservation education and helping people understand how important wolves are in the ecosystems in which they live.”

Wolves become lively and demonstrate their trademark behavior—the howl—as night falls and the air cools.

Wolves become lively and demonstrate their trademark behavior—the howl—as night falls and the air cools.

Leaders of the Pack

Home to six gray wolves today, Wolf Park at one time housed 24 wolves. Earlier research necessitated larger sample sizes. Now that wolves can be studied in the wild, the park intentionally keeps its pack smaller to provide exemplary care and oversight, though Rawlings says the park plans to have pups next spring.

Wolves aren’t the only residents at Wolf Park. The animal curators also care for red and gray foxes and a herd of 11 American bison. Klinghammer introduced bison to the park in the 1980s to conduct predator-prey behavioral research through a controlled program. He found the bison were perfectly capable of evading the wolves.

“Wolves and bison are both historically native species in this area that can no longer be found here in the wild,” Rawlings says. “From a conservation perspective, it’s important to talk about why these species were eliminated and how that affects the ecosystem.”

The park has also displayed hand-reared coyotes in the past and hopes to acquire some more once improvements to the coyote enclosure are complete.

“Highlighting existing native species such as foxes and coyotes is a good way to teach our visitors about coexisting with wildlife,” Rawlings says. “These are animals you might come across in your own backyard. It’s helpful to educate on the differences between coyotes and wolves because a lot of people think they’ve seen a wolf, but it was most likely a coyote because we don’t have wild wolves in Indiana.”

The Purdue Student Chapter of Environmental Education is working with park staff to identify native plant and animal species that exist naturally within the park and develop signage to educate parkgoers.

Life at the Park

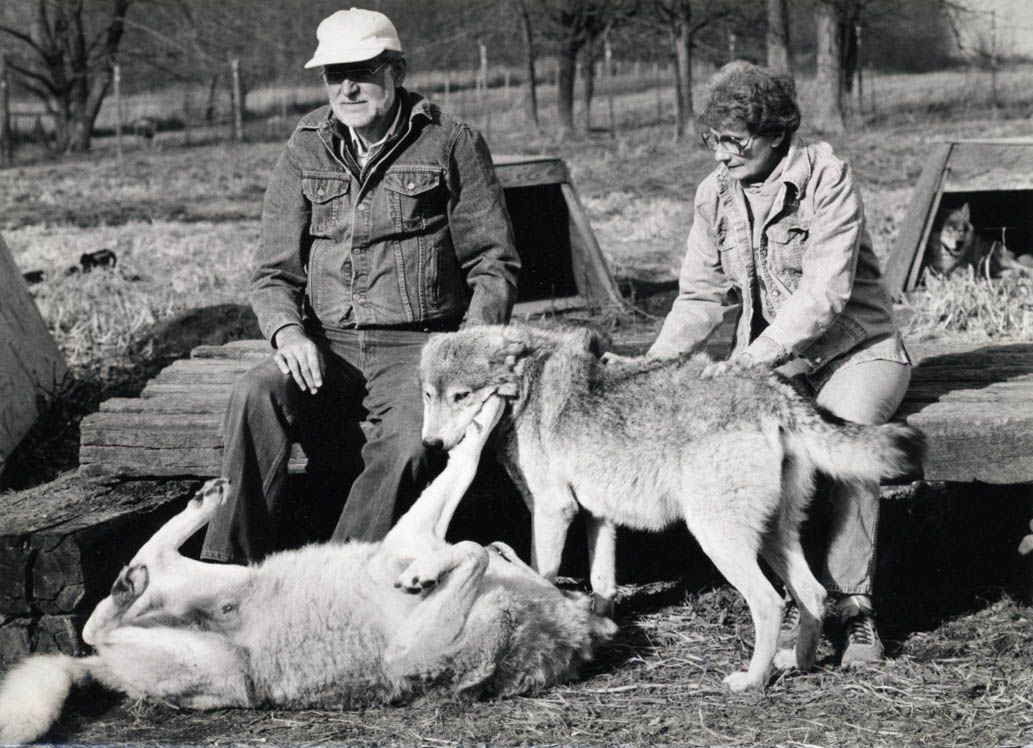

Today, Wolf Park manages 75 acres of historic farmland that houses its natural habitats. The park manages an additional 27 acres of conservation property, recently converted from farmland, focused on providing shelter for northern bobwhites.

Hear the call of the northern bobwhite:

The park continues to collaborate with scientists seeking to conduct research, including investigations into howling, scent rolling, reproductive behavior, aggression, rank order, human interaction time lengths, pointing, opening apparatuses, and feeding patterns.

“Wolf Park remains dedicated to research, education, and conservation,” Rawlings says. “Those were the founding principles established by Dr. Klinghammer.”

Staff perform daily welfare checks on the animals and continually train them. Training the animals to interact with their human caretakers has benefits for the wolves, too. Wolves in the wild generally live three to five years. In captivity, wolves can live up to 20.

“A lot of the training we do involves preparing for medical care, such as blood draws, vaccinations, and taking pills,” Rawlings says. “Because we’ve trained our animals to be comfortable with medical procedures, when it comes time for actual medical treatments or examinations by our veterinarians, they don’t require sedation as often, which can be dangerous for wild animals.”

Guests are encouraged to howl along as wolves serenade the park.

Guests are encouraged to howl along as wolves serenade the park.

Wolf Park provides opportunities for the public to visit the wolves, including its popular Howl Nights—the wolves are most active at dawn and dusk. The park regularly conducts tours of its grounds. Visiting animal sponsorships allow sponsors to visit, under staff supervision, the enclosures of the animals of their choice.

“A visit to Wolf Park is a chance to see these magnificent animals up close and learn more about them and how you can advocate for wildlife,” Goodmann says. “There are two broad misunderstandings the public has about wolves. The first is that they’re bloodthirsty killers—they’ll kill for fun; they’ll kill livestock; and they’ll kill more than they can eat. The other is they are noble creatures of the forest who are naturally monogamous and only take what they need to live. The truth lies somewhere in the middle.”

“I love wolves, but unless we save the Earth as we know it, the wolves will not matter either. To me, they are a symbol of the wilderness which we must preserve at all costs—along with all the other things we hold dear.”

—Erich Klinghammer

ANIMAL AMBASSADORS

Wolf Park’s socialized animals serve as ambassadors for their wild relatives. Each of the species is historically or currently native to Indiana.

Visit the park’s website to learn how you can sponsor an ambassador and contribute to conservation, education, and animal welfare.

Red foxes have excellent hearing—they can hear rodents digging miles underground.

Red foxes have excellent hearing—they can hear rodents digging miles underground.

Gray wolves have a complex communication system that involves body language, barking, growling, dancing, howling, and scent marking.

Gray wolves have a complex communication system that involves body language, barking, growling, dancing, howling, and scent marking.

Bison are mosaic grazers—otherwise known as picky eaters. They eat mostly grasses and selectively avoid other plants, which influences prairie diversity. (Video has no sound)

Bison are mosaic grazers—otherwise known as picky eaters. They eat mostly grasses and selectively avoid other plants, which influences prairie diversity. (Video has no sound)

Gray wolves are the largest living wild canine species.

Gray wolves are the largest living wild canine species.

Red foxes exhibit a variety of colors, including solid black and solid white.

Red foxes exhibit a variety of colors, including solid black and solid white.

Wolf Park has been home to a small herd of bison since 1982.

Wolf Park has been home to a small herd of bison since 1982.

Read more stories from this issue of Purdue Alumnus magazine.

View a text-only version of this story.