ROLE OF A

LIFETIME

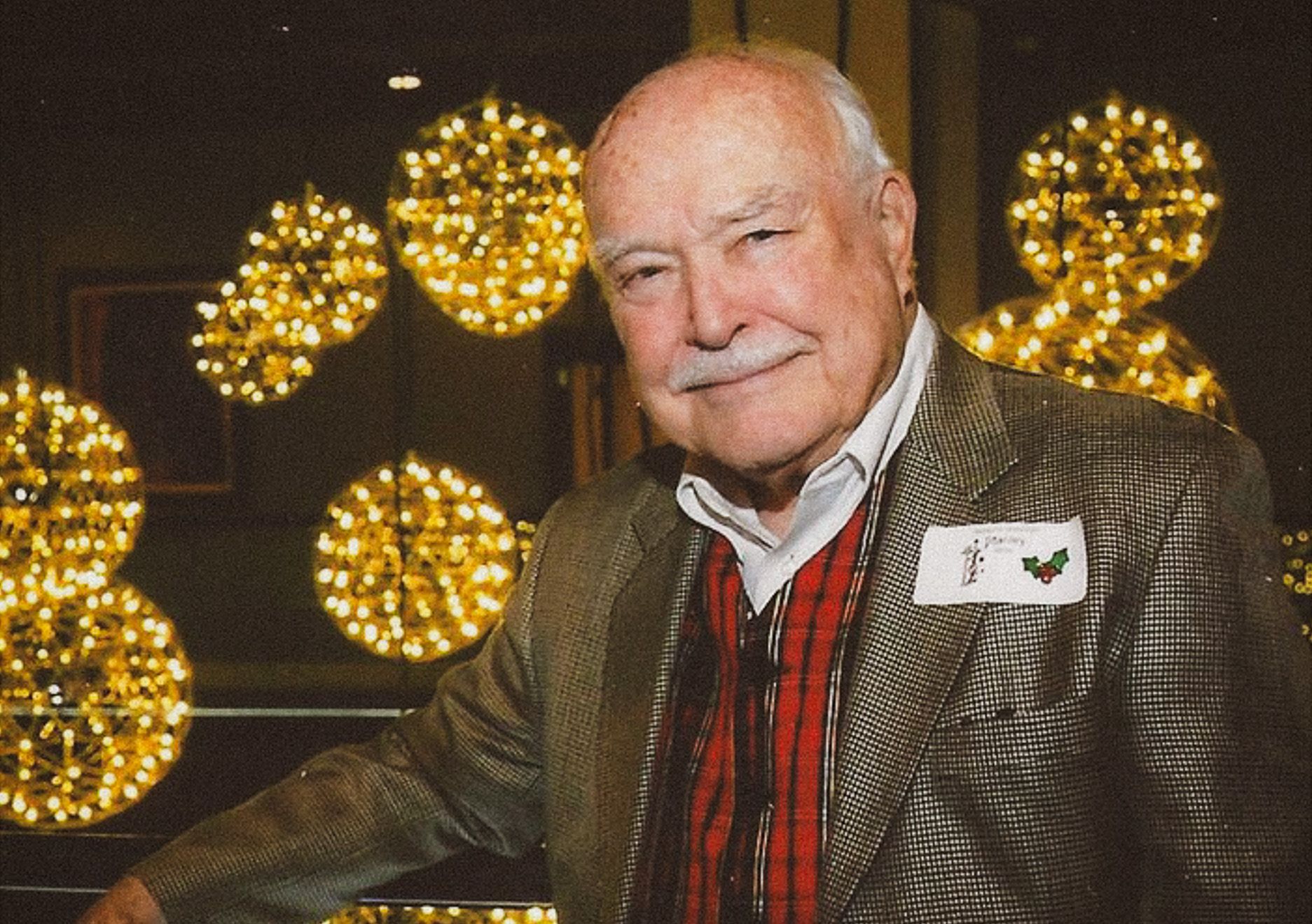

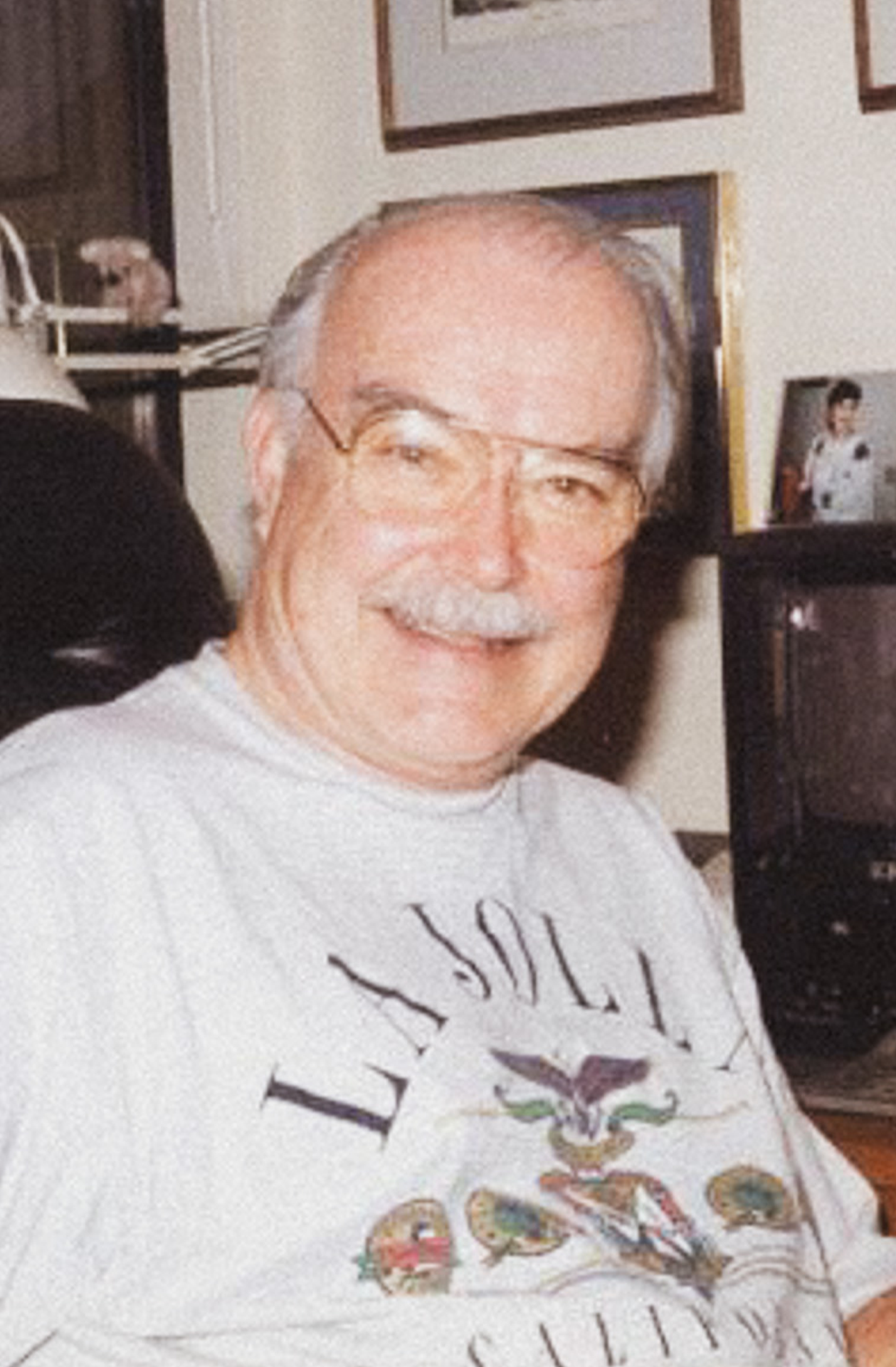

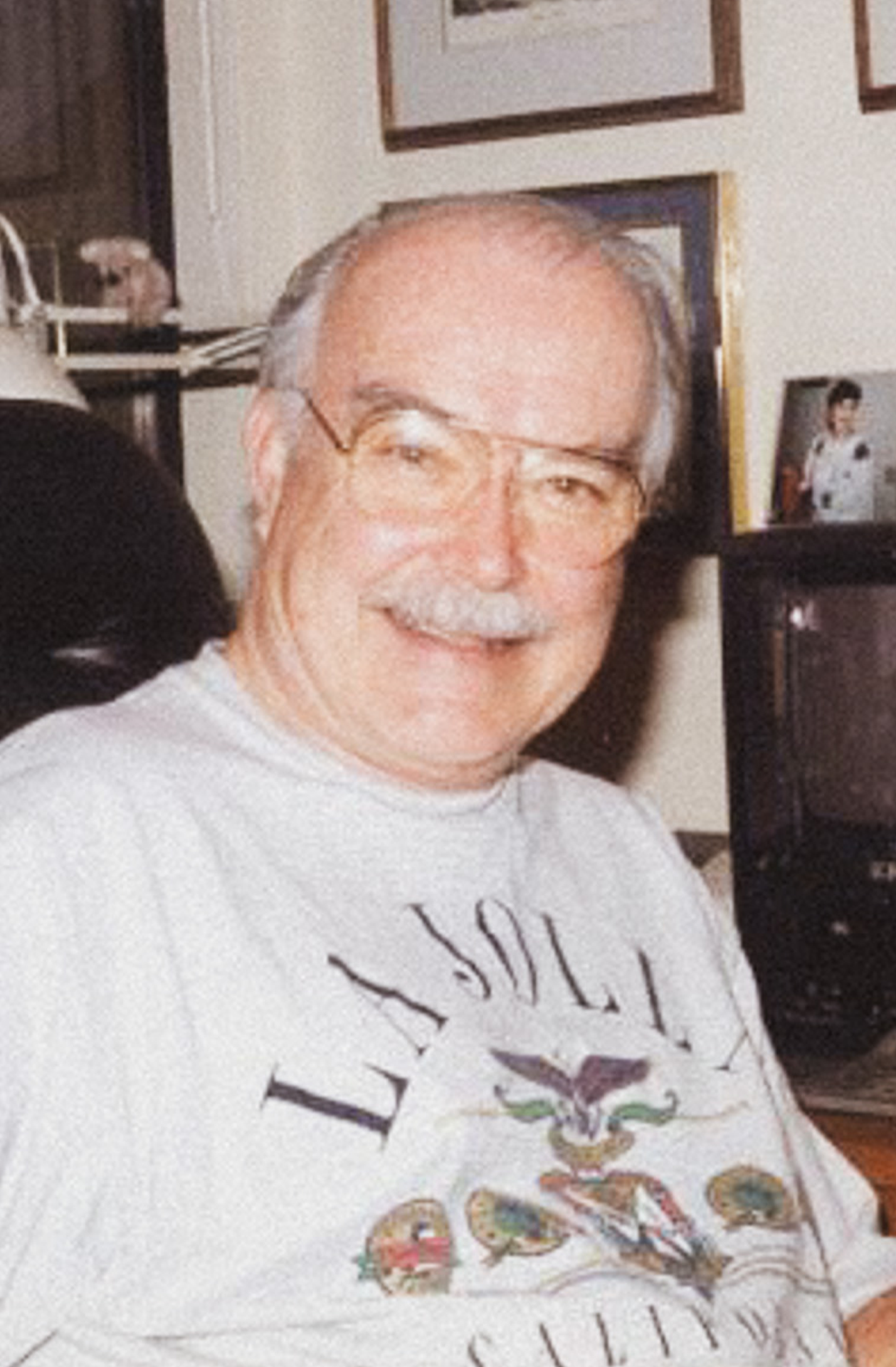

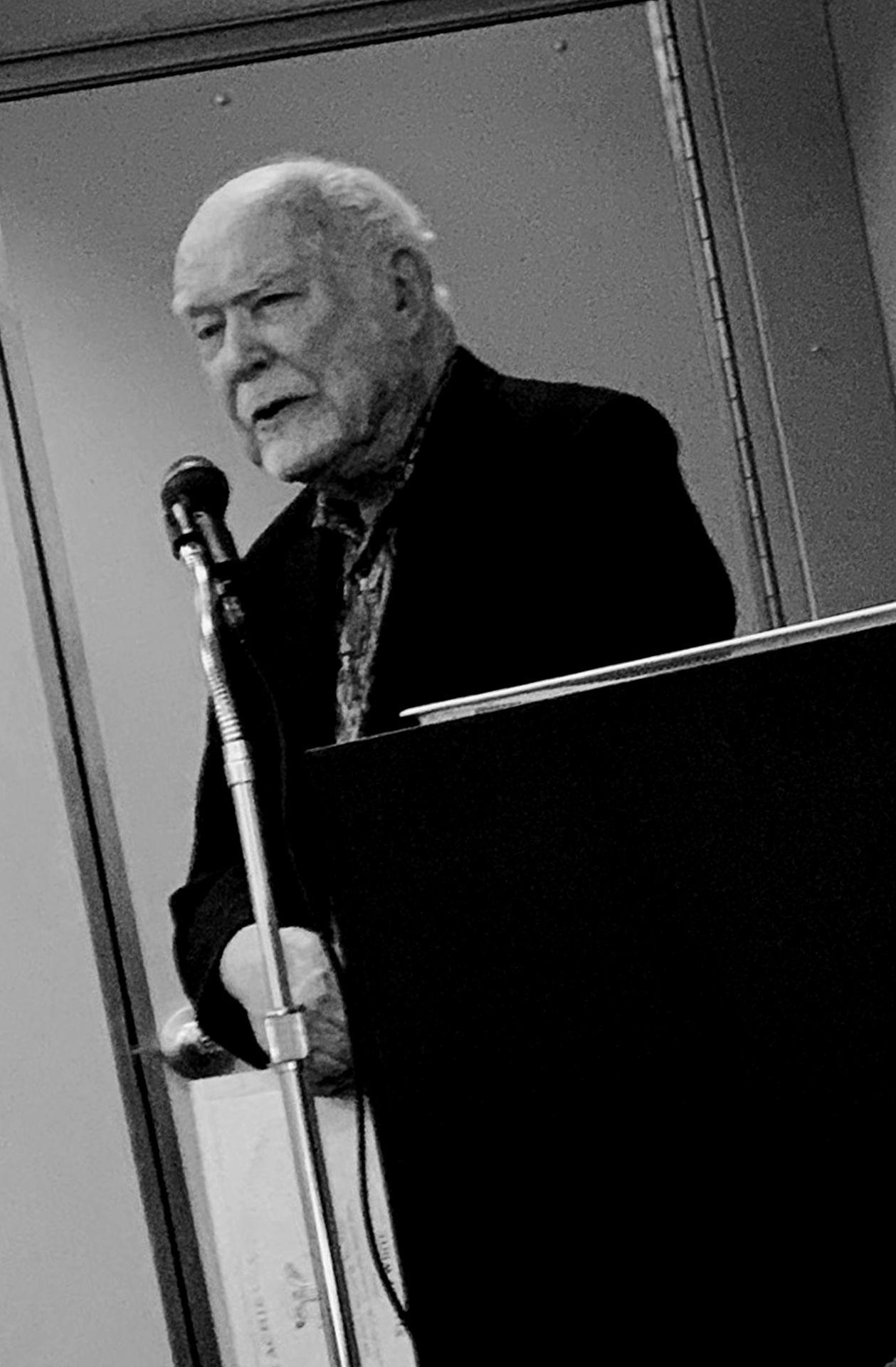

When you’re a Purdue graduate and you have lived to be 91 years old, there’s a good chance you’ve enjoyed a rich and fulfilling life. Even by these standards, Stan White stands out.

Scholar, soldier, engineer. Inventor, author, professor. Company man and family man. Community and professional leader, amateur pilot, newscaster and radio host, lay minister, singer, and international lecturer.

White (ECE’57, MS ECE’59, PhD ECE’65) has filled each of these roles at different stages of his life. In fact, he often filled multiple roles at once. Yet in true Boilermaker fashion, White somehow found time to play one more part—that of volunteer, taking care of others.

No matter where life took him, White always made sure to give back. And he gave back a lot.

“If there’s one thing I want to be remembered for, it’s helping others.”

White was formally recognized for his decades of service in April 2023, when he received the President’s Call to Service Award for outstanding public service. Also referred to as the President’s Lifetime Achievement Award, the honor is awarded by the president of the United States to people who have completed more than 4,000 hours of community service. It represents the highest level of the President’s Volunteer Service Award and is given to relatively few individuals.

“I grew up during the Depression and World War II, and that was a period of deprivation and hardship for everyone,” White says. “I learned that you need to help one another—that’s just what life is. I’m thrilled and honored to receive the award, knowing I’m a member of the ranks with a very small group of people I admire so much. If there’s one thing I want to be remembered for, it’s helping others.”

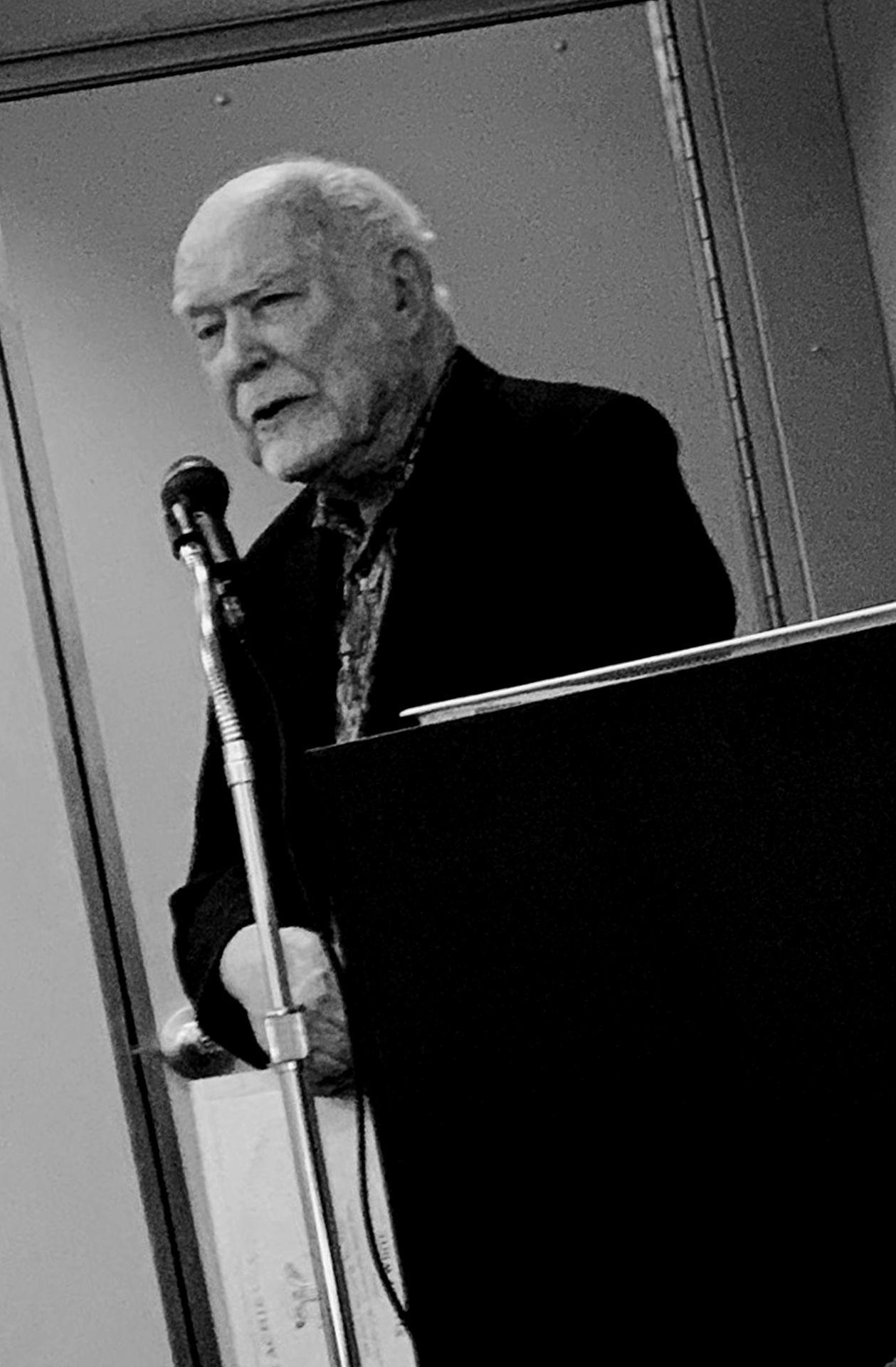

JEDICKS PATH

Stan White discusses the principles that guide his approach to life.

White received the President’s Call to Service Award for a very specific reason: He logged more than 4,000 documented hours as a clinical on-the-floor volunteer in intensive care units at the Providence Mission Hospital in Mission Viejo, California. But he also spent countless undocumented hours volunteering over the years, often supporting veterans, the homebound, and the ill.

White’s desire to support veterans stems from his time in the U.S. Air Force during the Korean War, an experience that disrupted White’s college education but served as a catalyst for his later career. His drive to volunteer in medical settings comes from a deep personal connection with patients and their care.

“I want to lift people up and bring them along.”

White and his wife, Edda, had four children. All of them died by the age of 44, one from acute lymphocytic leukemia and three from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. In 1986, White was stricken with adult-onset hydrocephalus—also known as normal-pressure hydrocephalus (NPH)—an incurable but treatable disorder that can often go undiagnosed.

White wandered from neurologist to neurologist for 20 years before he stumbled across a hydrocephalus conference in Gothenburg, Sweden. After reading abstracts on the disorder and connecting with the UCLA neurosurgery department, White volunteered to participate in a research program, learned about his options, and underwent ventriculoatrial shunt surgery in 2007. He has had no NPH problems since.

“Now, I’m old but healthy,” he says.

White enjoys counseling NPH patients because he has “been there and done that,” understands their problems, and can offer advice and genuine friendship.

“Personally, I have been very blessed by all the opportunities I’ve had and how things have aligned for me, but I know firsthand what it’s like to face those tough personal challenges,” White says. “People sometimes need help remembering that life can bring you so many wonderful, wonderful things. I want to lift people up and bring them along, and I dive right in. Plenty, in every sense, is meant to be shared.”

The origins of White’s dynamic life trajectory can be traced, at least in part, to his intrepid parents.

White’s father worked as an engineer around the world, including on the construction of the Panama Canal, and moonlighted as a fiction writer. He served during both WWI and WWII, ultimately dying during the later conflict. White’s mother enjoyed a decade of child stardom in vaudeville before settling down to raise a family and work as an editor and proofreader.

“My father was a great engineer, and he taught me so much—father to son and friend to friend,” White says. “One thing I learned from my parents was to live an interesting life and do the work you really want to do.”

“When you’re excited about something, you pour your whole self into it.”

Having inherited his father’s affinity for engineering, White later worked with classified missile technology during his own time in the military. He also made important connections in the industry. Further inspired by the Soviet Union’s launch of the Sputnik satellite in 1957, White focused his graduate education on aerospace engineering.

“That was a very good time to be an engineer with a military background,” White says. “There was opportunity everywhere I went, and I wanted to be a sponge for as much stuff as I could sop up. I was more interested in challenge and excitement than salary, so I found myself doing very interesting work with people who were just as excited as I was. When you’re excited about something, you pour your whole self into it.”

White’s career as an engineer and inventor spanned more than 50 years. He began at North American Aviation, which later became Rockwell International. Upon retirement from Rockwell, he founded his own consultancy, SPACECorp, and Rockwell became his most important client.

White also served as a consultant for NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the U.S. Department of Defense, and the National Science Foundation, among several other prominent aerospace organizations. His work as an inventor led to more than 100 patents, many of which are still classified.

Additionally, White enjoyed a 32-year career as a professor in the University of California system. In retirement, he continued his life as an educator by giving lectures in Europe and Asia.

“Looking back, I feel like I always had a guardian angel looking out for me,” White says. “There just always seemed to be another door opening. But as the saying goes, luck is when opportunity meets preparedness—and I was always trying to be the most prepared person possible. I just kept getting assignments, kept chugging away, kept learning. Suddenly, you’re the expert, and another opportunity arises.”

Hear Stan White’s career and life advice—for engineers and anyone interested in finding joy and helping others.

Purdue honored White as a Distinguished Engineering Alumnus in 1988 and as an Outstanding Electrical Engineer in 1992. He was also elected as an American Association for the Advancement of Science fellow and awarded with the Leonardo da Vinci Medallion, among many other honors.

White says that his Purdue education, combined with influential mentors he encountered throughout his career, helped lay the foundation for his success.

“Wherever the most interesting things were going on, it seemed like it was primarily Purdue people in the room,” White says. “There were people from MIT and Stanford and Caltech that were high performers, but Purdue was dominant. That was striking. Beginning with my dad, I became accustomed to turning to mentors. I found mentors everywhere, people who believed in me and urged me to push myself—and there were mentors galore at Purdue.”

“I don’t think I could have gotten a better education in my field than the one I got at Purdue.”

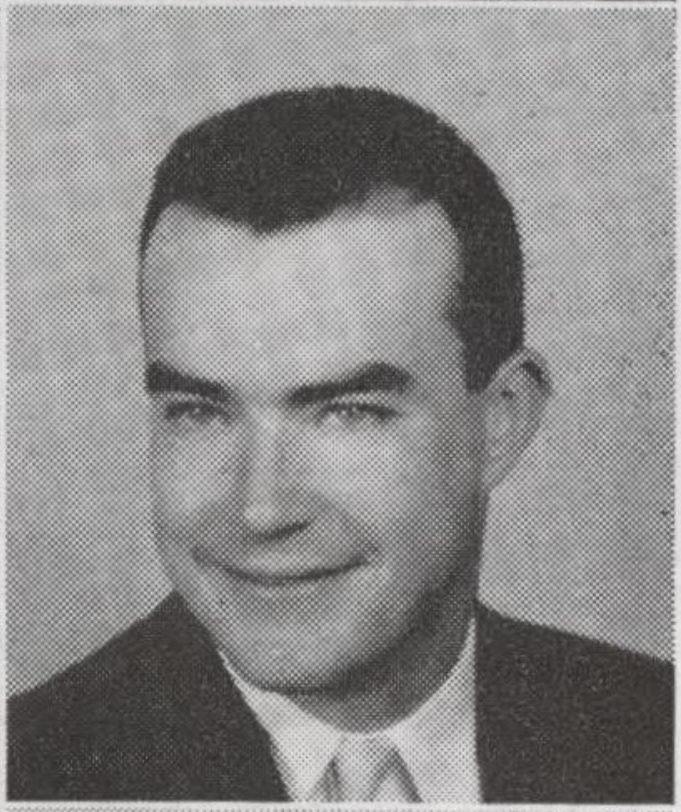

Stan White in 1957 for the Debris yearbook

Stan White in 1957 for the Debris yearbook

Stan White in 1957 for the Debris yearbook