STICKING THE (LUNAR) LANDING

// By Hannah Davis

“Reach for the moon and you’ll land among the stars” is turning out to be more than just an expression for Benjamin Tackett (AAE’15, MS AAE’21).

A spacecraft systems engineer at Firefly Aerospace, his post-graduation trajectory found him playing a part in the momentous January launch of Blue Ghost, a semiautonomous unmanned lunar lander.

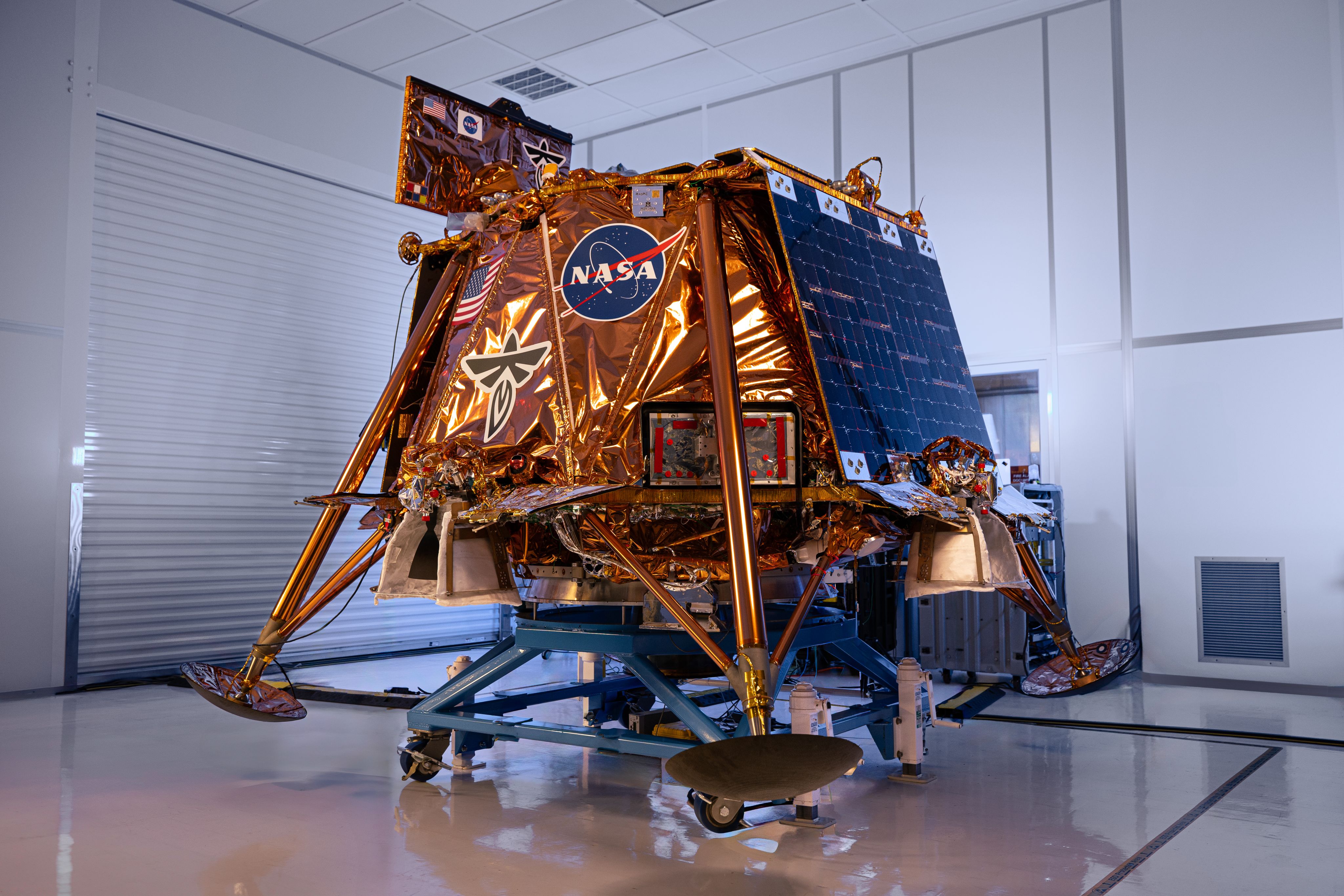

A part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) initiative, Blue Ghost was designed to transport cargo anywhere on the lunar surface. It was launched aboard a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Kennedy Space Center in Florida and spent 45 days traveling to the moon. Performing the first fully successful commercial moon landing, Blue Ghost delivered 10 science and technology instruments known as payloads.

I ALWAYS WANTED TO DO SOMETHING CUTTING EDGE WITH TECHNOLOGY.

For Tackett—who is originally from Saint Charles, Illinois—contributing to Blue Ghost’s mission was the culmination of a lifelong drive to be involved in innovation. His senior design project, a collaboration with Buzz Aldrin to design a conceptual humans-to-Mars colonization mission, ultimately got Tackett “hooked on space.”

That project served as his springboard to secure a summer fellowship at the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, where he worked on entry, descent, and landing technologies. His interest in all things aerospace grew, and he obtained his master’s in aeronautics and astronautics from Purdue, focused heavily on hypersonic mission design and aerodynamics and subsystems engineering.

“At Purdue, I really learned how to design and fully run missions that require reentry technologies—basically anything that comes back from space,” he says.

Tackett then spent five years at NASA Langley Research Center in Virginia, working exclusively in flight mechanics and hypersonic mission design, before starting at Firefly. Based in Cedar Park, Texas, Firefly has more than 700 employees with about 100 of them involved or fully dedicated to Blue Ghost’s mission.

As a systems engineer, Tackett frequently collaborates with others in a team setting, and he believes natural self-starters are well suited to roles like his.

“I’m surrounded by people who, after completing one project, quickly say to themselves, ‘Okay, I finished this thing, and now I'm going to find a new thing to tackle and just dive into it,’” he says.

Tackett’s role on the operations side of missions involves managing risks, changes, and requirements while maintaining a big-picture view of the vehicle from as many aspects as possible.

“We make sure that the program is working toward its goals without letting any subsystem collide with another,” he says.

Days can vary, depending on the mission demands.

“One day could be spent reassessing and evaluating our mass load for the program and then collaborating with subsystem engineers to track everything against their specific requirements,” Tackett says. “One day will be very focused on risk review and mitigations, and another one might be focused heavily on changes that are being proposed by the program and how those benefit and impact every other system that goes into a current mission.”

When Blue Ghost successfully landed on March 2, Tackett says he and his coworkers experienced a mix of “joy, astonishment, relief, and a healthy dose of awe. It was an incredibly emotional experience for everyone who had a role—a top life event that’s going to be pretty hard to beat.”

Blue Ghost had completed 346 hours of surface operations by the time the robotic lander sent its final transmissions back to Earth on March 16. Future missions are currently being planned.

Long term, Tackett would like to lead some of the first lunar sample-return missions of the modern era. Wherever his path leads, he says his Purdue education prepared him to conquer professional challenges.

“I CREDIT PURDUE FOR MAKING REALLY GOOD PROBLEM-SOLVERS OUT OF ITS STUDENTS AND ENGINEERS.”