// By George Spencer

Friendship, justice, and learning. That’s the motto of Sigma Chi, Purdue University’s first fraternity.

In Purdue’s early days, ideals such as these bound its young students both socially and spiritually—giving them a shared sense of hope for the future at a school that was literally and figuratively at the edge of a frontier.

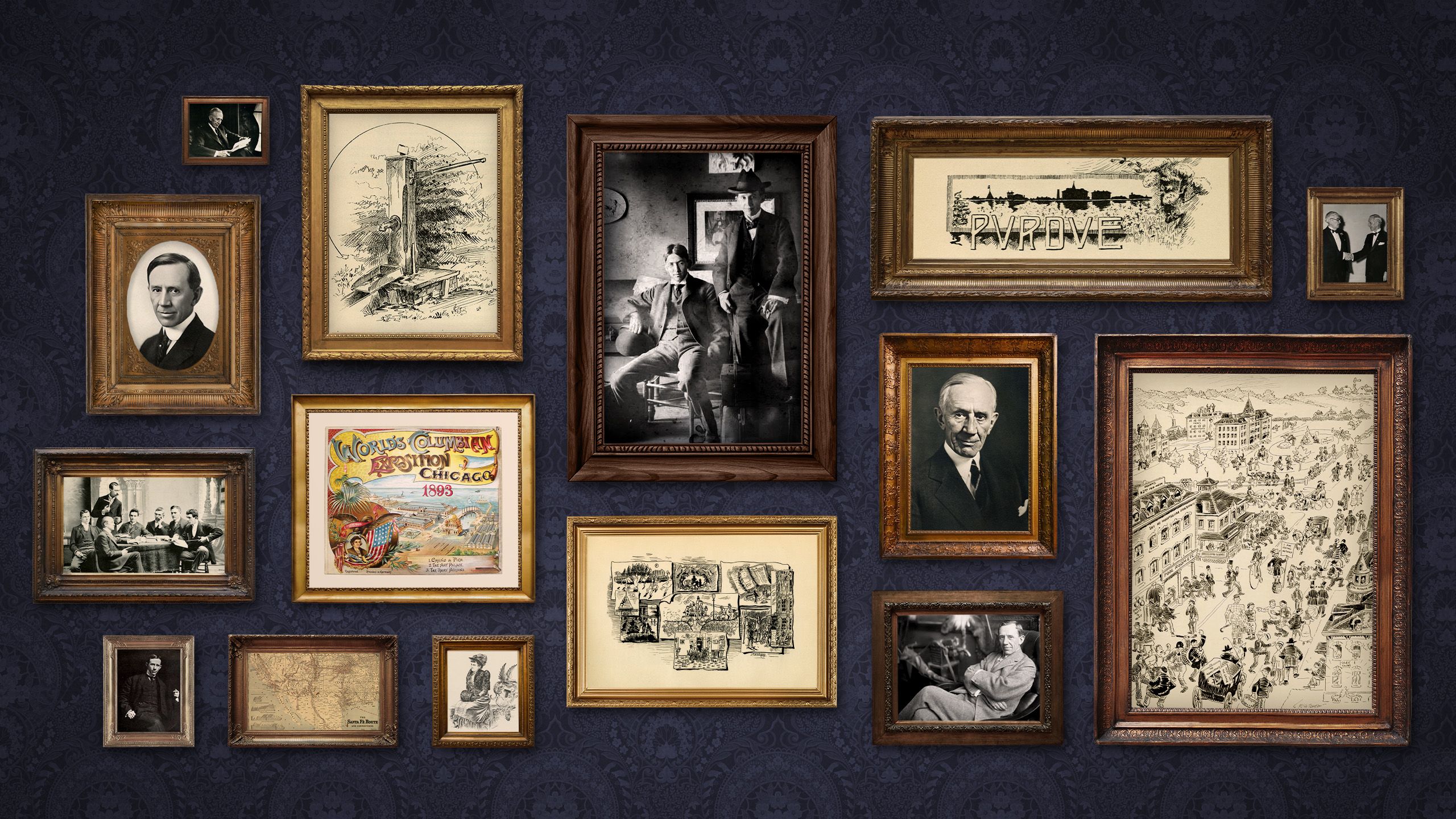

Among the students who attended Purdue in the late 1800s were inventor David Ross; writers George Ade and Booth Tarkington; cartoonist John T. McCutcheon; and politician Chase Osborn.

Some were Sigma Chi brothers. All were remarkable trailblazers who went on to enjoy mind-boggling careers.

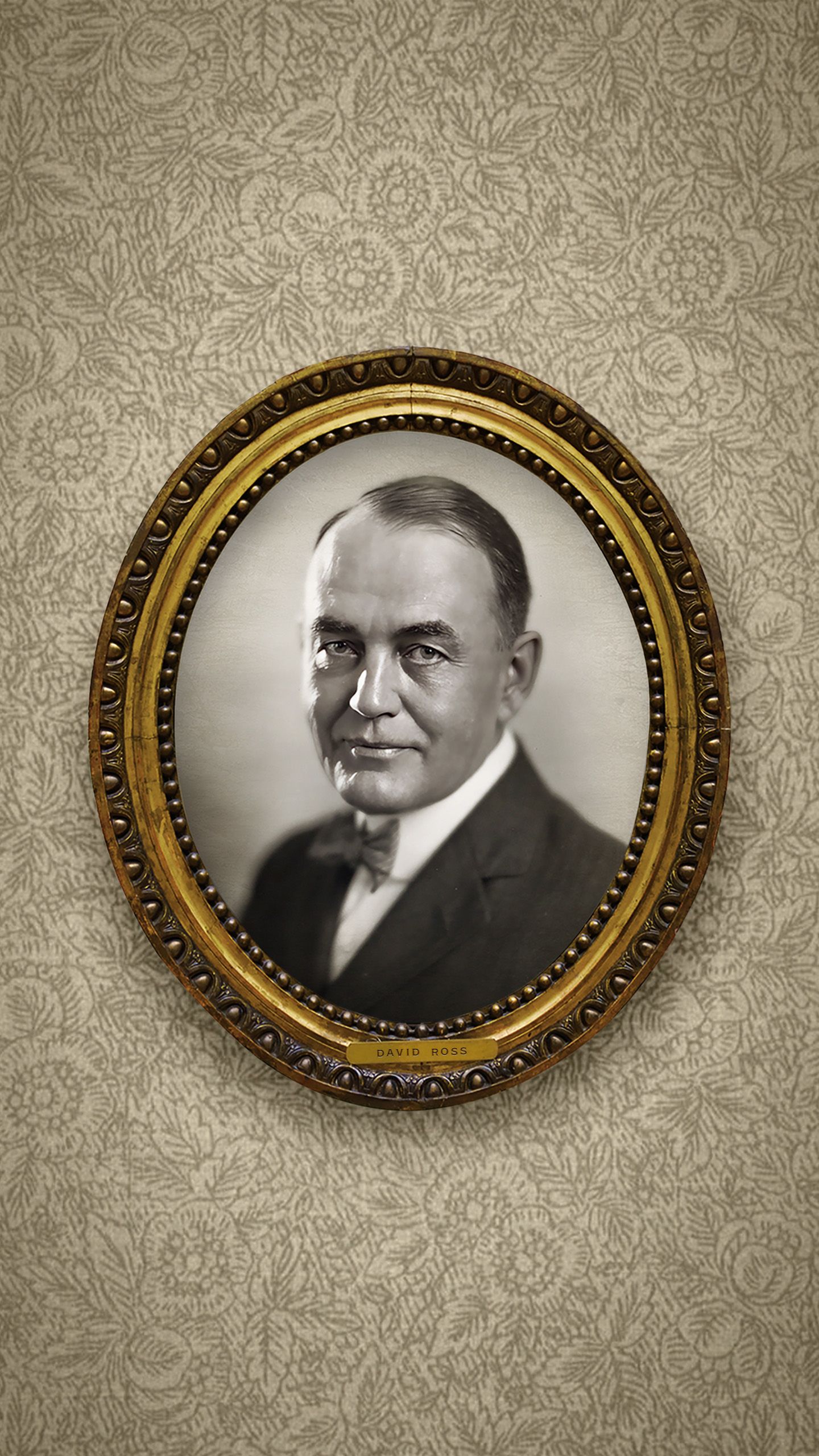

Ross (ME’1893), a storekeeper’s son, may rank as the alumnus who had more influence on Purdue than any other. But growing up, his parents wondered what would become of him. On a Wabash River steamboat ride, they feared their boy had fallen overboard, only to find him in the engine room, mesmerized by churning pistons.

Though Ross did poorly in his machine-design classes at Purdue, his world-class achievements as an inventor and entrepreneur led one Hoosier governor to dub him Indiana’s No. 1 Citizen. Curious about how early autos worked, he studied their flaws. The result? He received 32 game-changing car- and truck-related patents for steering gears, axles, and differentials—the system that transfers power from engines to wheels.

Like famed inventor Thomas Edison, it seemed this wizard of Lafayette could invent anything. Ross also won patents for dozens of products that ranged from an improved dirigible airship frame and reflective traffic devices to a three-piece canoe and a round barn designed to withstand high winds.

During his lifetime, the longtime Purdue Board of Trustees member gave gifts worth millions to the university, often anonymously, including support for the Purdue Airport and the Purdue Research Foundation.

A bachelor, Ross joked, “Some men keep race horses or women. I’d rather help support a university.”

One day in the early 1920s, Ross invited Ade for a walk on a 65-acre farm near campus. When they came to a rise overlooking a huge natural depression, Ross shared his dream of building a stadium in the hollow.

“Interesting,” Ade replied. “I was in the old stadium in Athens in 1896, and this does look to be about the same size.”

Ross already had an option on the land, and the two men agreed to finance its purchase, help pay for construction, and name it Ross-Ade Stadium. They agreed that since Ross had done most of the planning, his name would come first. But Ade was worried. “Lemonade, orangeade, and now Ross-Ade!” he exclaimed. “What are people going to say?”

Ross (ME’1893), a storekeeper’s son, may rank as the alumnus who had more influence on Purdue than any other. But growing up, his parents wondered what would become of him. On a Wabash River steamboat ride, they feared their boy had fallen overboard, only to find him in the engine room, mesmerized by churning pistons.

Though Ross did poorly in his machine-design classes at Purdue, his world-class achievements as an inventor and entrepreneur led one Hoosier governor to dub him Indiana’s No. 1 Citizen. Curious about how early autos worked, he studied their flaws. The result? He received 32 game-changing car- and truck-related patents for steering gears, axles, and differentials—the system that transfers power from engines to wheels.

Like famed inventor Thomas Edison, it seemed this wizard of Lafayette could invent anything. Ross also won patents for dozens of products that ranged from an improved dirigible airship frame and reflective traffic devices to a three-piece canoe and a round barn designed to withstand high winds.

During his lifetime, the longtime Purdue Board of Trustees member gave gifts worth millions to the university, often anonymously, including support for the Purdue Airport and the Purdue Research Foundation.

A bachelor, Ross joked, “Some men keep race horses or women. I’d rather help support a university.”

One day in the early 1920s, Ross invited Ade for a walk on a 65-acre farm near campus. When they came to a rise overlooking a huge natural depression, Ross shared his dream of building a stadium in the hollow.

“Interesting,” Ade replied. “I was in the old stadium in Athens in 1896, and this does look to be about the same size.”

Ross already had an option on the land, and the two men agreed to finance its purchase, help pay for construction, and name it Ross-Ade Stadium. They agreed that since Ross had done most of the planning, his name would come first. But Ade was worried. “Lemonade, orangeade, and now Ross-Ade!” he exclaimed. “What are people going to say?”

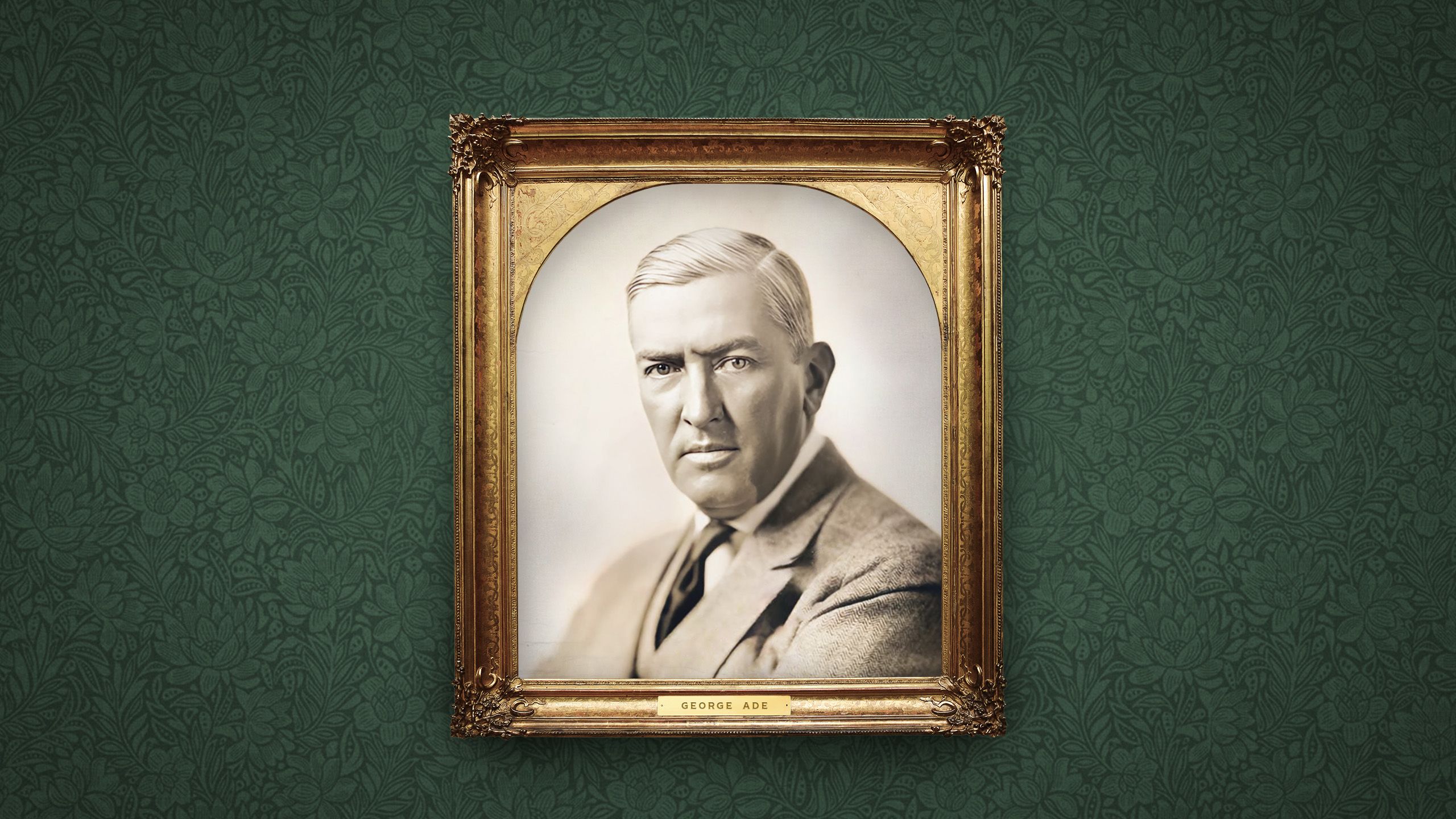

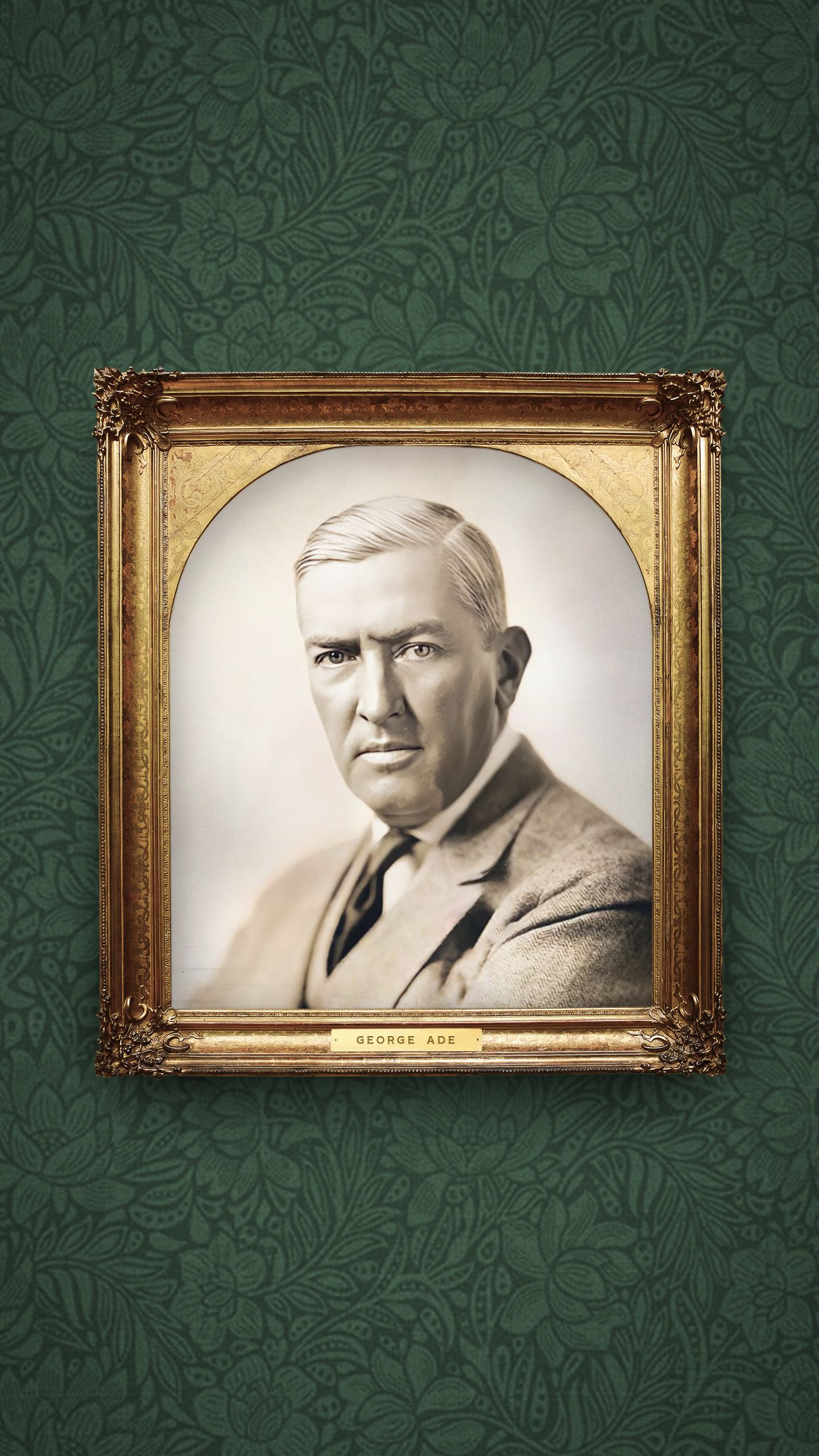

Like Ross, playwright Ade (S’1887, HDR LA’1926) struggled at Purdue. The tall, thin son of a Kentland, Indiana, bank cashier, he told friends he graduated at the top of his class—alphabetically. He let nothing deter him from seeing shows at Lafayette’s Grand Opera House. Ade was “unable to resist the theatre, just as a mouse is weak in the presence of cheese,” a biographer wrote.

Ade attended law school but quit after a few weeks, opting instead for the livelier occupation of newspaper reporter in Lafayette and then Chicago. The bright lights of the big city lured him from an early age—one of his first memories is of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 illuminating the night sky above his father’s farm.

Stardom greeted the cub reporter when the passenger ship Tioga exploded in the Chicago River. Ade was the only reporter in the newsroom. His spellbinding account inspired editors to assign him to top stories like heavyweight prizefights and labor strikes.

Ade could do it all. Promoted to columnist, he penned Aesop-like fables about oddball country characters who used real-life slang. A smash with readers, his stories were nationally syndicated and collected in book form.

Then Broadway called. Ade’s first play, 1902’s The Sultan of Sulu did boffo biz. The story was based on the exploits of an intrepid college friend.

Two years later, he based The College Widow not on Purdue but on nearby Wabash College because he considered Wabash more “provincial.” The football-themed comedy was a hit and continued to fill seats even after his next two plays premiered, a feat that made Ade the first playwright in history to have three shows on Broadway at the same time.

When his theatrical fame faded, Ade wrote screenplays for silent movies, including Back Home and Broke and Woman Proof.

He had a “pen tipped in gold,” according to author Lee Coyle. “To Ade, life was an opalescent bubble of laughter to be loved for its lightness and brightness, but seldom to be taken seriously,” Coyle wrote.

Throughout his life, Ade generously supported Purdue. In addition to the football stadium, he helped fund the construction of the Memorial Gymnasium and Purdue Memorial Union. He was a member of the Board of Trustees and long-standing benefactor of Sigma Chi, even serving as the fraternity’s national president.

Like Ross, playwright Ade (S’1887, HDR LA’1926) struggled at Purdue. The tall, thin son of a Kentland, Indiana, bank cashier, he told friends he graduated at the top of his class—alphabetically. He let nothing deter him from seeing shows at Lafayette’s Grand Opera House. Ade was “unable to resist the theatre, just as a mouse is weak in the presence of cheese,” a biographer wrote.

Ade attended law school but quit after a few weeks, opting instead for the livelier occupation of newspaper reporter in Lafayette and then Chicago. The bright lights of the big city lured him from an early age—one of his first memories is of the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 illuminating the night sky above his father’s farm.

Stardom greeted the cub reporter when the passenger ship Tioga exploded in the Chicago River. Ade was the only reporter in the newsroom. His spellbinding account inspired editors to assign him to top stories like heavyweight prizefights and labor strikes.

Ade could do it all. Promoted to columnist, he penned Aesop-like fables about oddball country characters who used real-life slang. A smash with readers, his stories were nationally syndicated and collected in book form.

Then Broadway called. Ade’s first play, 1902’s The Sultan of Sulu did boffo biz. The story was based on the exploits of an intrepid college friend.

Two years later, he based The College Widow not on Purdue but on nearby Wabash College because he considered Wabash more “provincial.” The football-themed comedy was a hit and continued to fill seats even after his next two plays premiered, a feat that made Ade the first playwright in history to have three shows on Broadway at the same time.

When his theatrical fame faded, Ade wrote screenplays for silent movies, including Back Home and Broke and Woman Proof.

He had a “pen tipped in gold,” according to author Lee Coyle. “To Ade, life was an opalescent bubble of laughter to be loved for its lightness and brightness, but seldom to be taken seriously,” Coyle wrote.

Throughout his life, Ade generously supported Purdue. In addition to the football stadium, he helped fund the construction of the Memorial Gymnasium and Purdue Memorial Union. He was a member of the Board of Trustees and long-standing benefactor of Sigma Chi, even serving as the fraternity’s national president.

Ade’s fraternity brother McCutcheon (S’1889, HDR LA’1926) may have influenced the playwright’s decision to move to Chicago early in his career. A gangly, bony man, McCutcheon worked for the Chicago Daily News as a cartoonist and illustrator, and Ade joined him at the paper as a fledgling reporter.

There, the two became a dynamic journalistic duo.

McCutcheon, who was celebrated for his gentle humor and gift at capturing personalities, hit the streets with Ade. They covered everything from political rallies and crime to the World’s Columbian Exposition—Chicago’s 1893 world’s fair. With both men pressed for cash, they rented a third-floor room in a boardinghouse for $5 a week. To get by, they pawned their rings and watches to buy food.

“Tagging along with George, he chronicled and I illustrated almost every phase of Chicago’s life and activities,” McCutcheon recalled. “There was joy and zest and adventure in everything we did.”

An opportunity to illustrate a booklet on the Santa Fe Railroad system changed McCutcheon’s life. After journeying by stagecoach and train to California, he caught the adventure bug. He and Ade often traveled together, beginning with a European tour for the newspaper in 1895.

McCutcheon soon became a globe-trotting war correspondent and combat reporter. He switched papers in 1903, and his work appeared above the fold of the front page of the Chicago Tribune for the next 43 years, an honor that earned him a Pulitzer Prize and the nickname “Dean of American Cartoonists.”

During the Spanish-American War, McCutcheon went into battle with General MacArthur in the Philippines. One of only three journalists to witness the sinking of the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, he called the experience the greatest single event of his life.

Among McCutcheon’s many adventures, he explored the jungles of New Guinea, toured the Gobi Desert, flew on the Graf Zeppelin, hunted big game in Africa with Theodore Roosevelt, met Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, and rode on horseback in Iran.

In World War I, McCutcheon was captured by the Germans in Belgium. As a “quasi-prisoner,” he was taken aloft in a fighter and, from an altitude of 3,000 feet, witnessed an artillery duel on the battle lines. “Every moment, men were being torn to pieces,” he wrote.

That was not McCutcheon’s first flight. A 15-minute jaunt in 1910 had him perilously perched on the lower wing of a biplane owned by the Wright brothers.

McCutcheon became one of the nation’s highest-paid illustrators. On his death, the Tribune eulogized him by saying that “his special excellence lay in a combination of a highly developed sense of irony, a delight in the ridiculous, a small boy’s curiosity, a big boy’s delight in excitement and adventure, and an all-pervading warmth of personality.”

Ade’s fraternity brother McCutcheon (S’1889, HDR LA’1926) may have influenced the playwright’s decision to move to Chicago early in his career. A gangly, bony man, McCutcheon worked for the Chicago Daily News as a cartoonist and illustrator, and Ade joined him at the paper as a fledgling reporter.

There, the two became a dynamic journalistic duo.

McCutcheon, who was celebrated for his gentle humor and gift at capturing personalities, hit the streets with Ade. They covered everything from political rallies and crime to the World’s Columbian Exposition—Chicago’s 1893 world’s fair. With both men pressed for cash, they rented a third-floor room in a boardinghouse for $5 a week. To get by, they pawned their rings and watches to buy food.

“Tagging along with George, he chronicled and I illustrated almost every phase of Chicago’s life and activities,” McCutcheon recalled. “There was joy and zest and adventure in everything we did.”

An opportunity to illustrate a booklet on the Santa Fe Railroad system changed McCutcheon’s life. After journeying by stagecoach and train to California, he caught the adventure bug. He and Ade often traveled together, beginning with a European tour for the newspaper in 1895.

McCutcheon soon became a globe-trotting war correspondent and combat reporter. He switched papers in 1903, and his work appeared above the fold of the front page of the Chicago Tribune for the next 43 years, an honor that earned him a Pulitzer Prize and the nickname “Dean of American Cartoonists.”

During the Spanish-American War, McCutcheon went into battle with General MacArthur in the Philippines. One of only three journalists to witness the sinking of the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay, he called the experience the greatest single event of his life.

Among McCutcheon’s many adventures, he explored the jungles of New Guinea, toured the Gobi Desert, flew on the Graf Zeppelin, hunted big game in Africa with Theodore Roosevelt, met Mexican revolutionary leader Pancho Villa, and rode on horseback in Iran.

In World War I, McCutcheon was captured by the Germans in Belgium. As a “quasi-prisoner,” he was taken aloft in a fighter and, from an altitude of 3,000 feet, witnessed an artillery duel on the battle lines. “Every moment, men were being torn to pieces,” he wrote.

That was not McCutcheon’s first flight. A 15-minute jaunt in 1910 had him perilously perched on the lower wing of a biplane owned by the Wright brothers.

McCutcheon became one of the nation’s highest-paid illustrators. On his death, the Tribune eulogized him by saying that “his special excellence lay in a combination of a highly developed sense of irony, a delight in the ridiculous, a small boy’s curiosity, a big boy’s delight in excitement and adventure, and an all-pervading warmth of personality.”

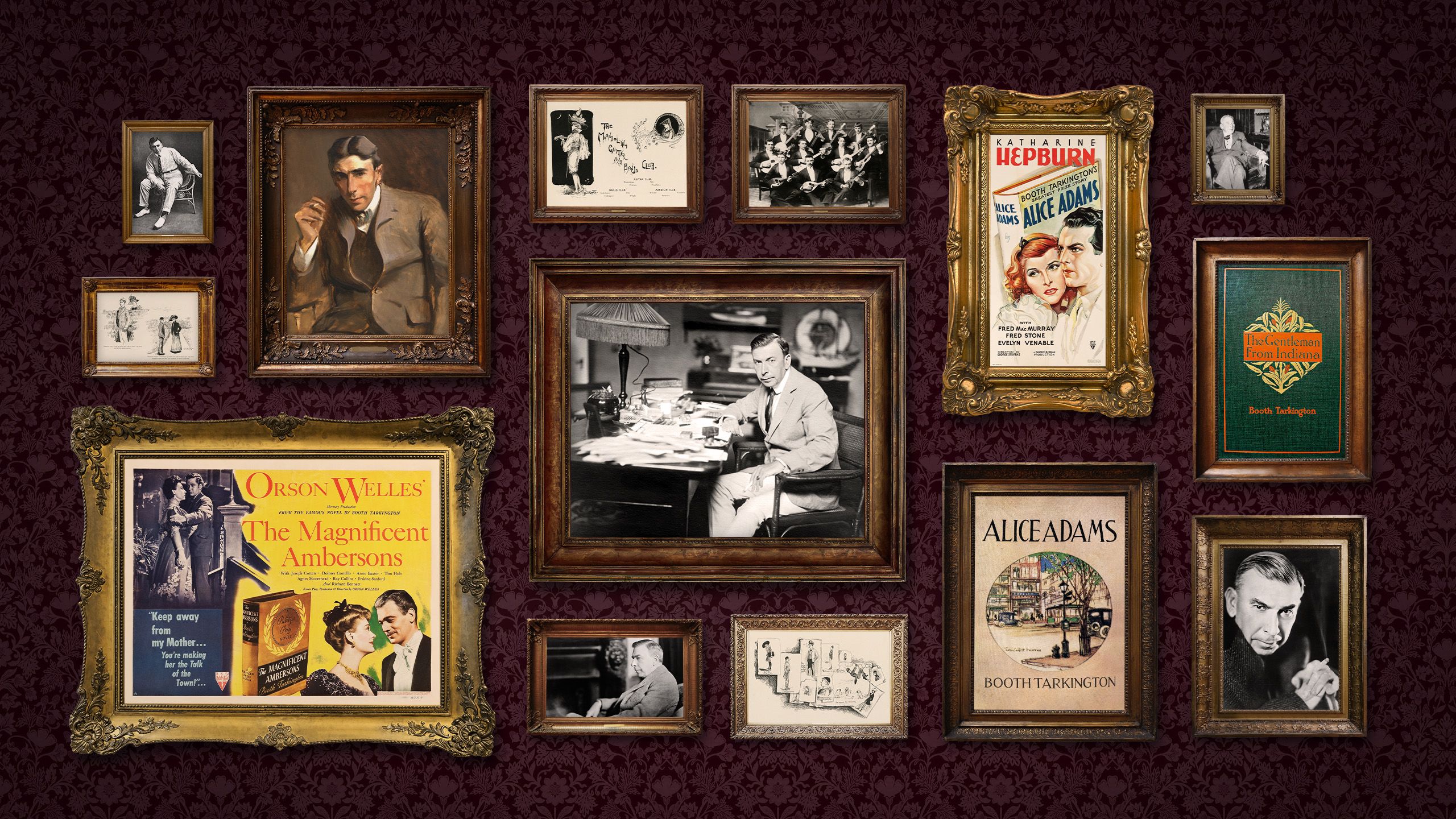

At Purdue, McCutcheon started as a student of mechanical engineering, a field which he later said was full of the “most malignant form of mathematics.” But his real gift during those years may have been in developing connections. He worked on the first Debris yearbook in 1889, and that’s where he met another contributor—the fledgling freshman artist Tarkington (HDR’40), a lanky youth whose nose was as prominent as Napoleon’s.

McCutcheon and Ade befriended the chain-smoking Tarkington, who they dubbed “Tark.”

Unlike McCutcheon, whose father worked hard as a cattle-driver and deputy sheriff of Tippecanoe County, Tarkington came from money. An Indianapolis native and the son of a judge, he prepped at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. After attending Purdue from 1890 to ’91, Tarkington transferred to Princeton. He later dropped out of Princeton and traded art for writing.

In early adulthood, the free-spirited Tarkington had an odd habit that amused friends. He would sometimes rise from bed in the middle of the night, put a fur coat on over his pajamas, and leave his home in search of curious folks to talk to—and possibly use as material in his fiction.

Tarkington found fame with the 1899 novel The Gentleman from Indiana, the first of his huge bestsellers. It remained so well known that the honorific title became synonymous with his name.

Tarkington wrote 40 novels, mostly about small-town midwestern life, as well as 20 plays. He twice won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction—in 1918 for The Magnificent Ambersons and in 1921 for Alice Adams. The Magnificent Ambersons was later developed into a 1942 movie directed by Orson Welles, and Alice Adams was turned into a 1935 movie starring Katharine Hepburn.

Critics compared Tarkington’s youthful prankster characters, like Penrod and Little Orvie, to Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer.

“What I’ve tried to do is show the truth about people’s insides, but I never want to be considered a realist,” he said.

At Purdue, McCutcheon started as a student of mechanical engineering, a field which he later said was full of the “most malignant form of mathematics.” But his real gift during those years may have been in developing connections. He worked on the first Debris yearbook in 1889, and that’s where he met another contributor—the fledgling freshman artist Tarkington (HDR’40), a lanky youth whose nose was as prominent as Napoleon’s.

McCutcheon and Ade befriended the chain-smoking Tarkington, who they dubbed “Tark.”

Unlike McCutcheon, whose father worked hard as a cattle-driver and deputy sheriff of Tippecanoe County, Tarkington came from money. An Indianapolis native and the son of a judge, he prepped at Phillips Exeter Academy in New Hampshire. After attending Purdue from 1890 to ’91, Tarkington transferred to Princeton. He later dropped out of Princeton and traded art for writing.

In early adulthood, the free-spirited Tarkington had an odd habit that amused friends. He would sometimes rise from bed in the middle of the night, put a fur coat on over his pajamas, and leave his home in search of curious folks to talk to—and possibly use as material in his fiction.

Tarkington found fame with the 1899 novel The Gentleman from Indiana, the first of his huge bestsellers. It remained so well known that the honorific title became synonymous with his name.

Tarkington wrote 40 novels, mostly about small-town midwestern life, as well as 20 plays. He twice won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction—in 1918 for The Magnificent Ambersons and in 1921 for Alice Adams. The Magnificent Ambersons was later developed into a 1942 movie directed by Orson Welles, and Alice Adams was turned into a 1935 movie starring Katharine Hepburn.

Critics compared Tarkington’s youthful prankster characters, like Penrod and Little Orvie, to Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer.

“What I’ve tried to do is show the truth about people’s insides, but I never want to be considered a realist,” he said.

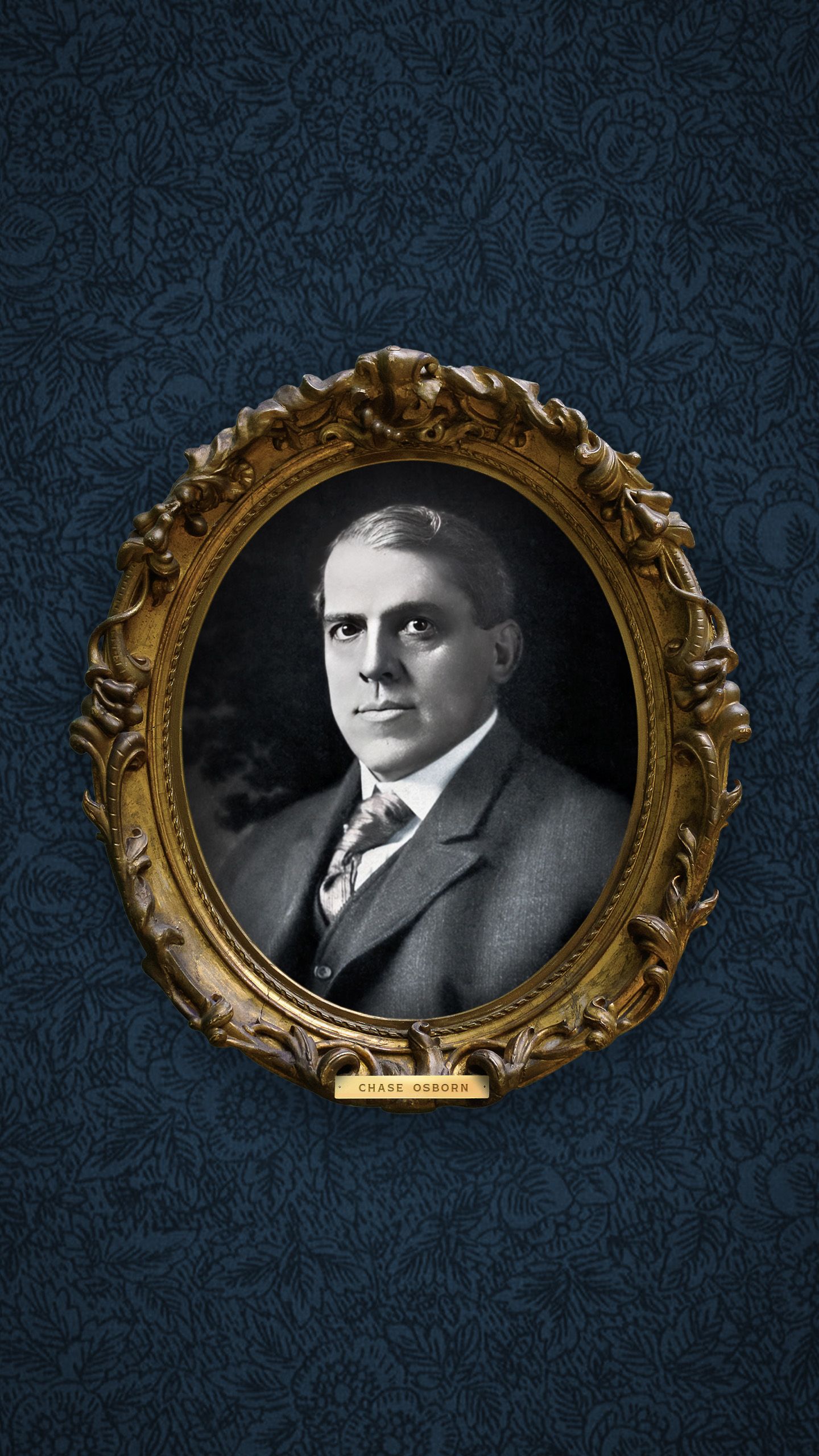

Of all the men from this storied group, Osborn may have led the most astonishing life. He entered Purdue at age 14 as a member of its first class but left the university at 17 and never graduated. “Mingled happiness and bitterness” marked his three years on campus.

After brawling with a bully during a church service, he walked from Lafayette to Chicago, sleeping in haystacks along the way. Arriving penniless, he slept in the railroad station and earned enough money to eat by carrying bags. Later, his fortunes improved—he found work as a potato peeler in a basement.

Born in a log cabin in Huntington County, Indiana, in 1860, Osborn earned the nickname “the Iron Hunter” due to his success at finding iron ore in the northern Great Lakes region. He became wealthy from timber deals and, at one point, owned Ontario’s Moose Mountain iron range.

“Six feet tall, hard as nails, and straight as an arrow, he thought nothing of hiking 10 to 50 miles a day carrying a pack of 25 to 100 pounds,” wrote an admirer. “At night, he slept in the open on a few balsam boughs.”

A true Horatio Alger, Osborn became Michigan’s governor in 1911 after serving as railroad commissioner—a position that allowed him to travel throughout the state on a special seat in a locomotive’s cowcatcher. He also published a crusading Upper Peninsula newspaper. Armed with a rifle to protect himself, he used the newspaper to denounce the “iron pirates” outlaw gang that terrorized the region.

“There was more hell raised when Chase was governor than at any time before or since,” said one statehouse observer.

Osborn signed workers’ compensation legislation, got the National Guard out of politics, and supported giving voting rights to women. Osborn’s many gifts to Purdue included 5,000 acres of Michigan timberland.

In his later years, Osborn explored the world—much as McCutcheon did—and lived part of the time in a log cabin on a farm in Georgia, where he wrote books such as Madagascar: Land of the Man-Eating Tree—though he admitted in its pages that no such thing existed.

Proud of his eccentricities, Osborn claimed during his elder years to be the only man in the world who rose at 3 a.m. and shaved in the dark while standing on one leg, a feat he said improved his coordination. When he died at age 89, an obituary reported that his motto was “The longer I live, the harder I find it to hate anyone. It makes me unhappy to hate anyone. It doesn’t pay.”

Spoken like a true Sigma Chi brother.

Of all the men from this storied group, Osborn may have led the most astonishing life. He entered Purdue at age 14 as a member of its first class but left the university at 17 and never graduated. “Mingled happiness and bitterness” marked his three years on campus.

After brawling with a bully during a church service, he walked from Lafayette to Chicago, sleeping in haystacks along the way. Arriving penniless, he slept in the railroad station and earned enough money to eat by carrying bags. Later, his fortunes improved—he found work as a potato peeler in a basement.

Born in a log cabin in Huntington County, Indiana, in 1860, Osborn earned the nickname “the Iron Hunter” due to his success at finding iron ore in the northern Great Lakes region. He became wealthy from timber deals and, at one point, owned Ontario’s Moose Mountain iron range.

“Six feet tall, hard as nails, and straight as an arrow, he thought nothing of hiking 10 to 50 miles a day carrying a pack of 25 to 100 pounds,” wrote an admirer. “At night, he slept in the open on a few balsam boughs.”

A true Horatio Alger, Osborn became Michigan’s governor in 1911 after serving as railroad commissioner—a position that allowed him to travel throughout the state on a special seat in a locomotive’s cowcatcher. He also published a crusading Upper Peninsula newspaper. Armed with a rifle to protect himself, he used the newspaper to denounce the “iron pirates” outlaw gang that terrorized the region.

“There was more hell raised when Chase was governor than at any time before or since,” said one statehouse observer.

Osborn signed workers’ compensation legislation, got the National Guard out of politics, and supported giving voting rights to women. Osborn’s many gifts to Purdue included 5,000 acres of Michigan timberland.

In his later years, Osborn explored the world—much as McCutcheon did—and lived part of the time in a log cabin on a farm in Georgia, where he wrote books such as Madagascar: Land of the Man-Eating Tree—though he admitted in its pages that no such thing existed.

Proud of his eccentricities, Osborn claimed during his elder years to be the only man in the world who rose at 3 a.m. and shaved in the dark while standing on one leg, a feat he said improved his coordination. When he died at age 89, an obituary reported that his motto was “The longer I live, the harder I find it to hate anyone. It makes me unhappy to hate anyone. It doesn’t pay.”

Spoken like a true Sigma Chi brother.