// By Marla Holt

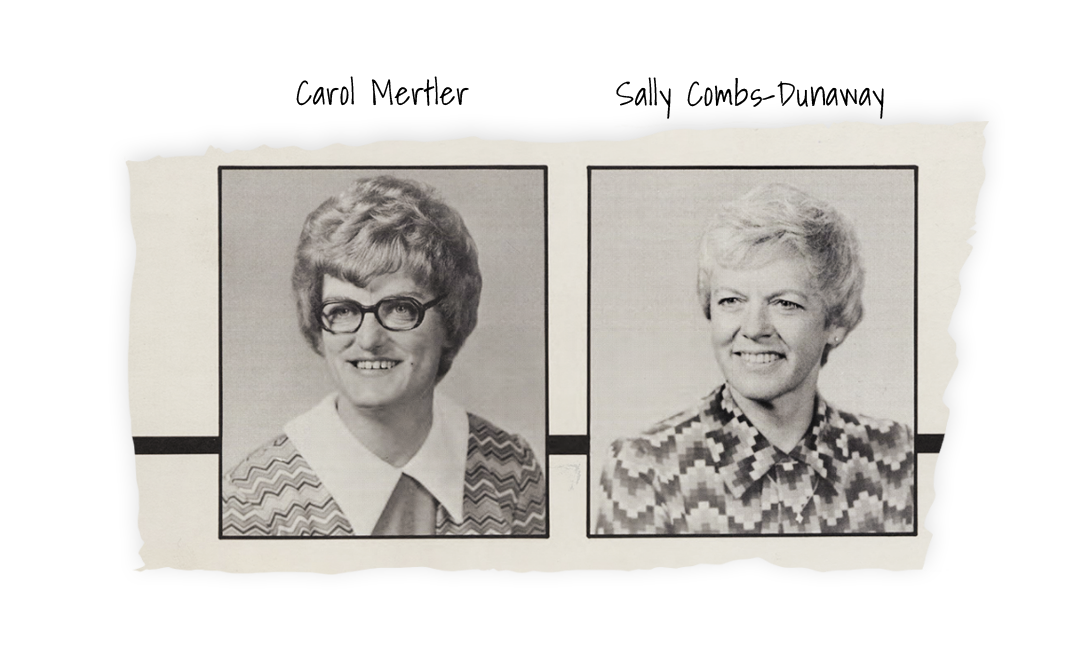

Female Boilermakers reflect on the impact

Title IX—now celebrating its 50th anniversary—had on women’s sports at Purdue.

// By Marla Holt

Female Boilermakers reflect on the impact Title IX—now celebrating its 50th anniversary—had on women’s sports at Purdue.

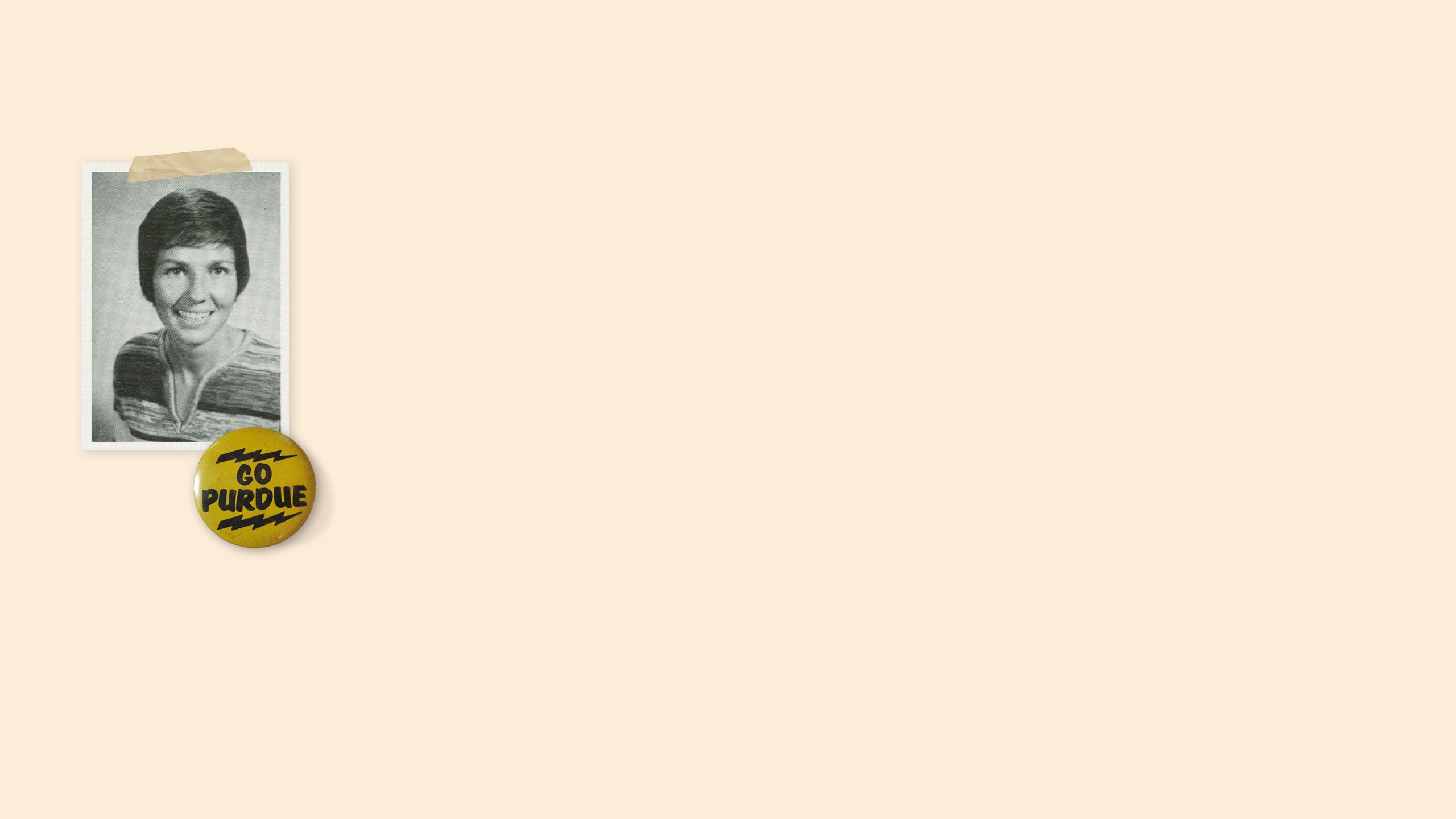

In the spring of 1975, not long after Amy Ruley (HHS’78) arrived at Purdue, she participated in a sit-in with other female students to demand that the university’s athletic department begin supporting women’s athletics.

Three years earlier, Congress had passed the Education Amendments Act, which contained a provision—known as Title IX—that included the following 37 words: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Title IX applied to any programs a school offered, but the most glaring inequity was in athletics.

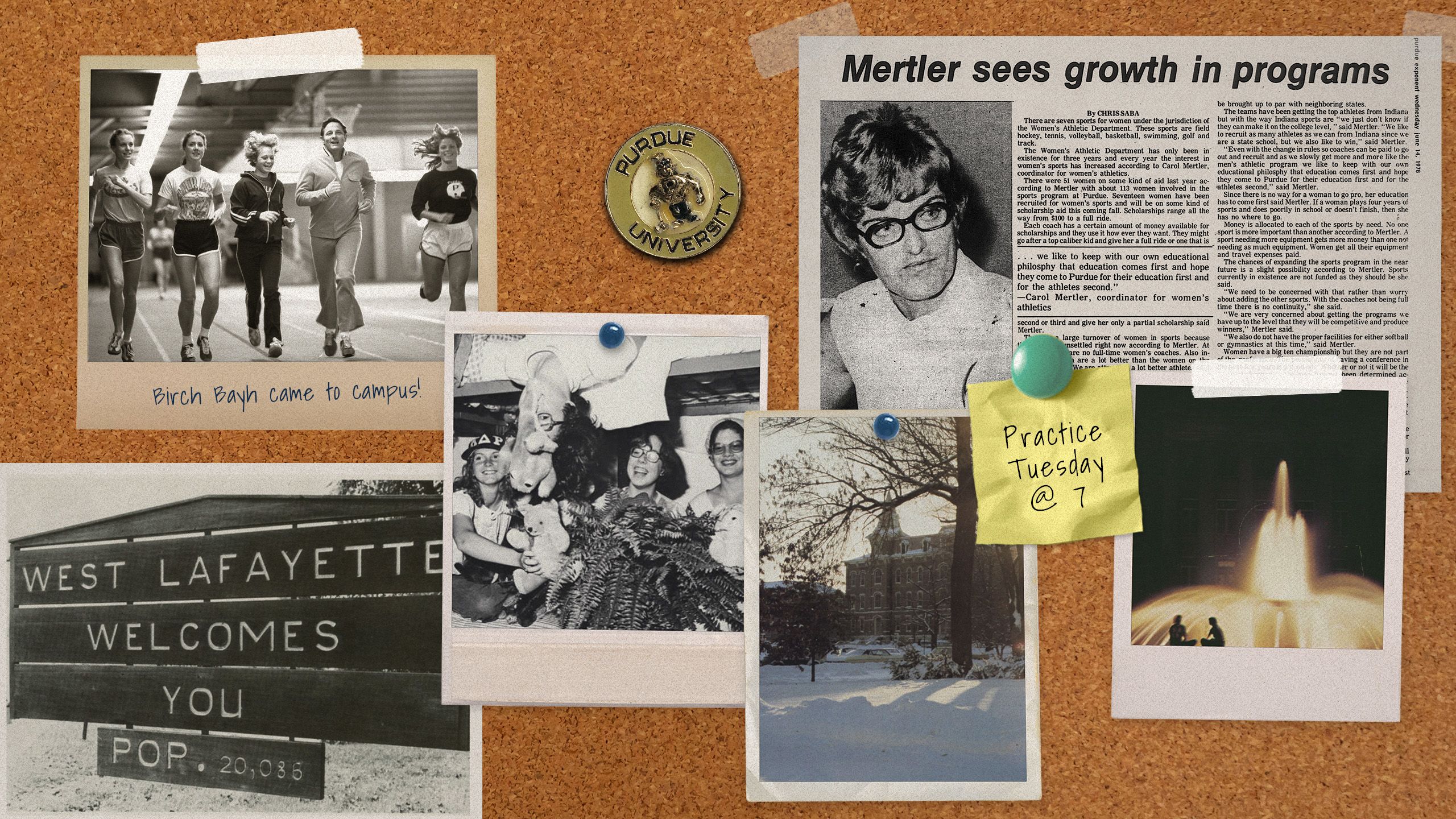

“We felt it was time for Purdue to support women’s athletics in the way it supported the men’s teams,” says Ruley, who recruited friends and family to join the cause. During her first year at Purdue, women were only allowed to play athletics under the direction of the Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Organization, which functioned as a club operated by students, often without coaching.

In the spring of 1975, not long after Amy Ruley (HHS’78) arrived at Purdue, she participated in a sit-in with other female students to demand that the university’s athletic department begin supporting women’s athletics.

Three years earlier, Congress had passed the Education Amendments Act, which contained a provision—known as Title IX—that included the following 37 words: “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving federal financial assistance.”

Title IX applied to any programs a school offered, but the most glaring inequity was in athletics.

“We felt it was time for Purdue to support women’s athletics in the way it supported the men’s teams,” says Ruley, who recruited friends and family to join the cause. During her first year at Purdue, women were only allowed to play athletics under the direction of the Women’s Intercollegiate Sports Organization, which functioned as a club operated by students, often without coaching.

As women became more vocal about the inequities they faced, doors began to open.

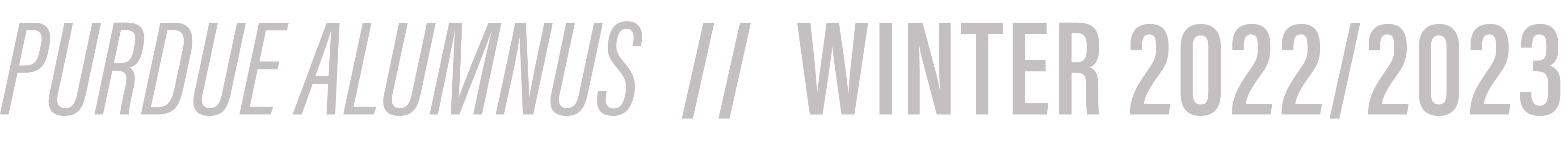

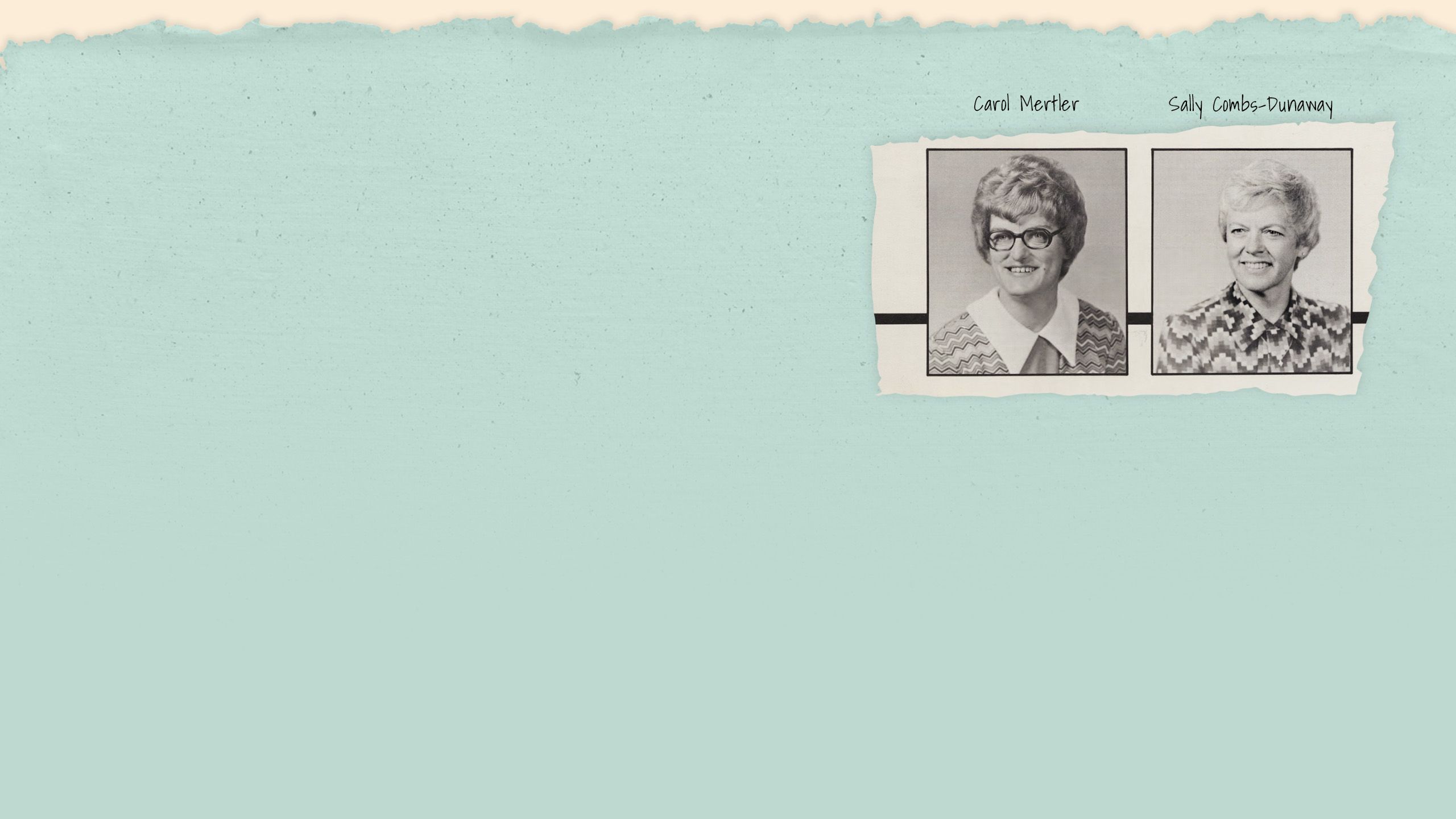

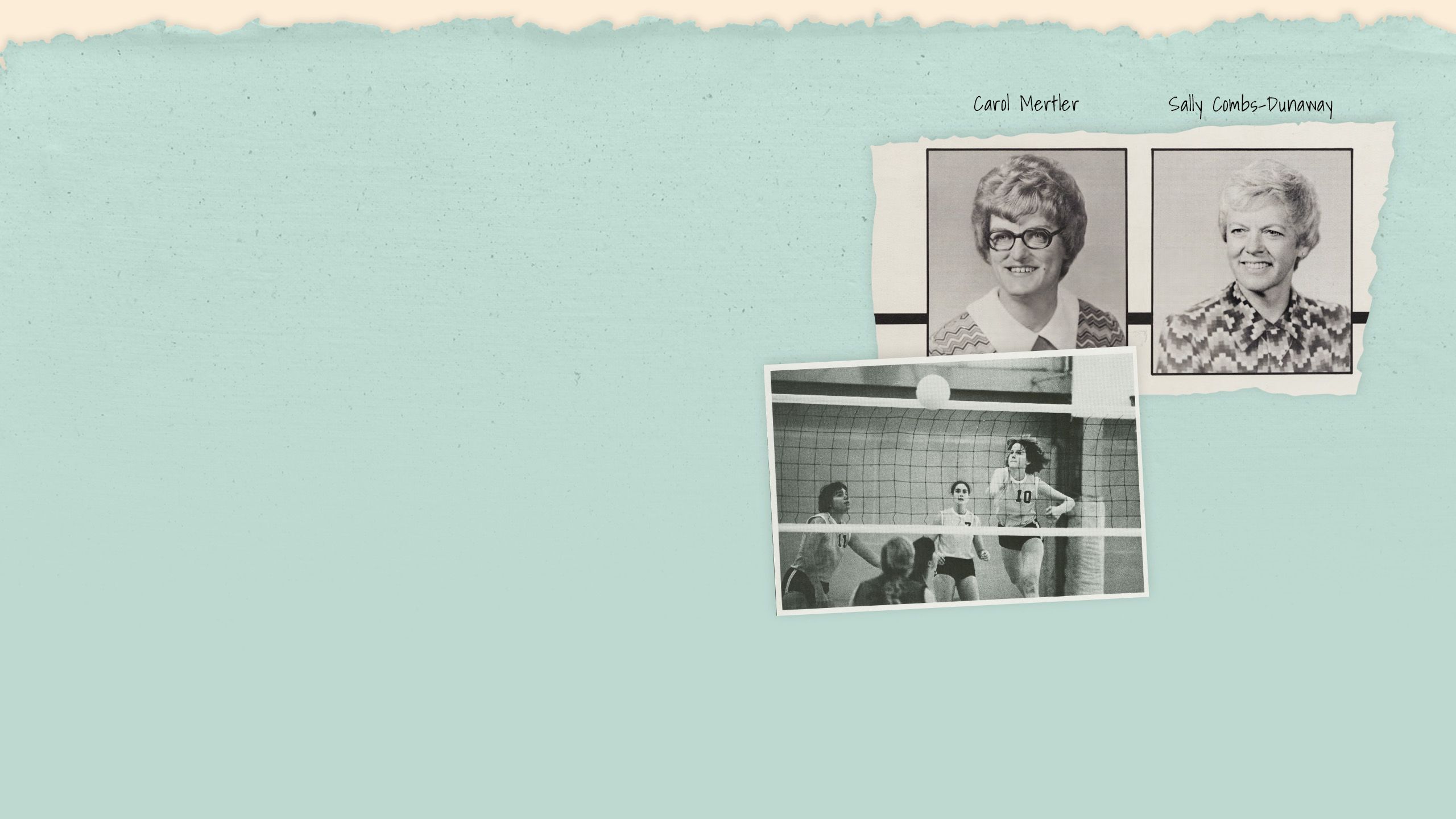

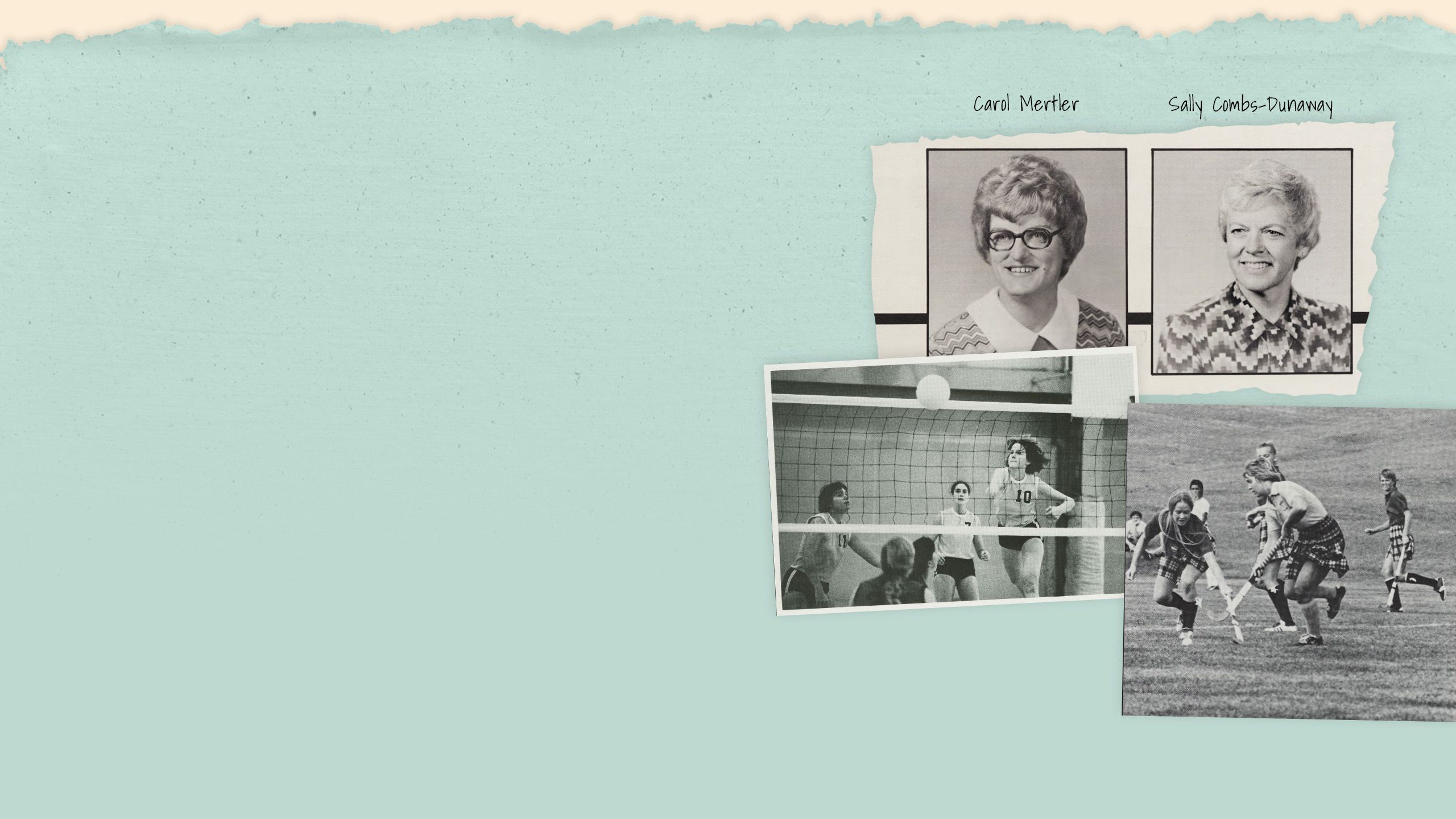

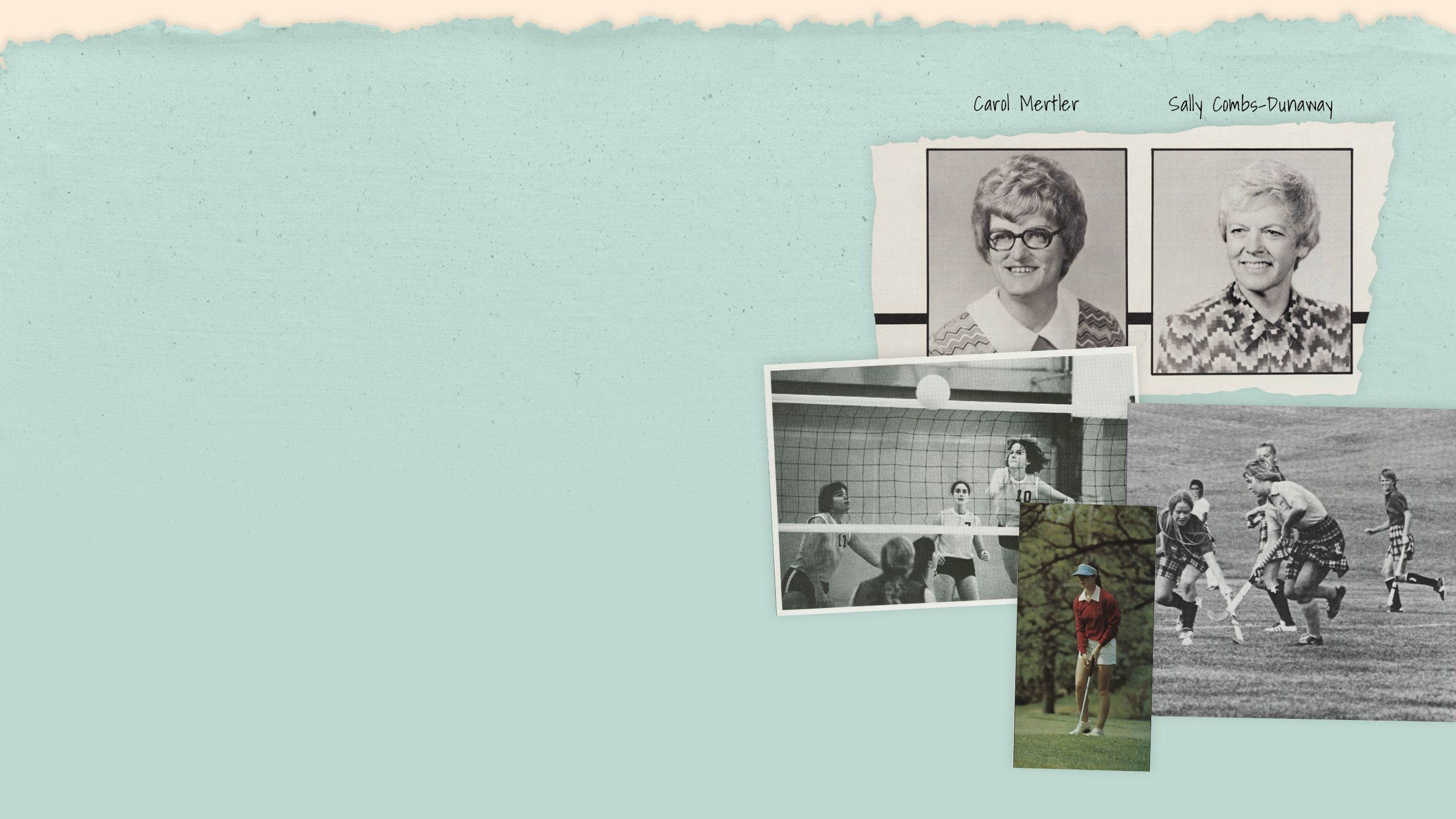

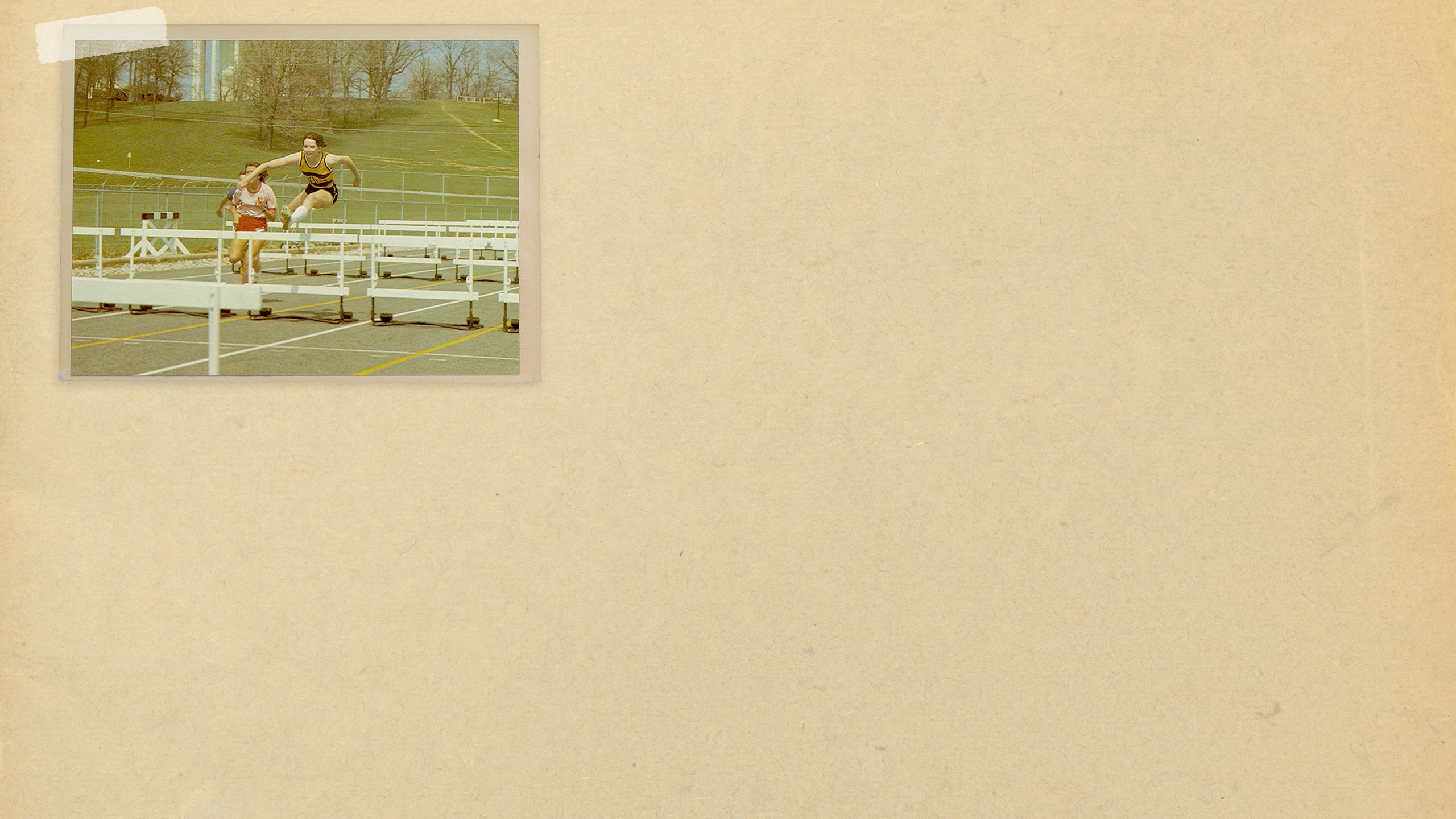

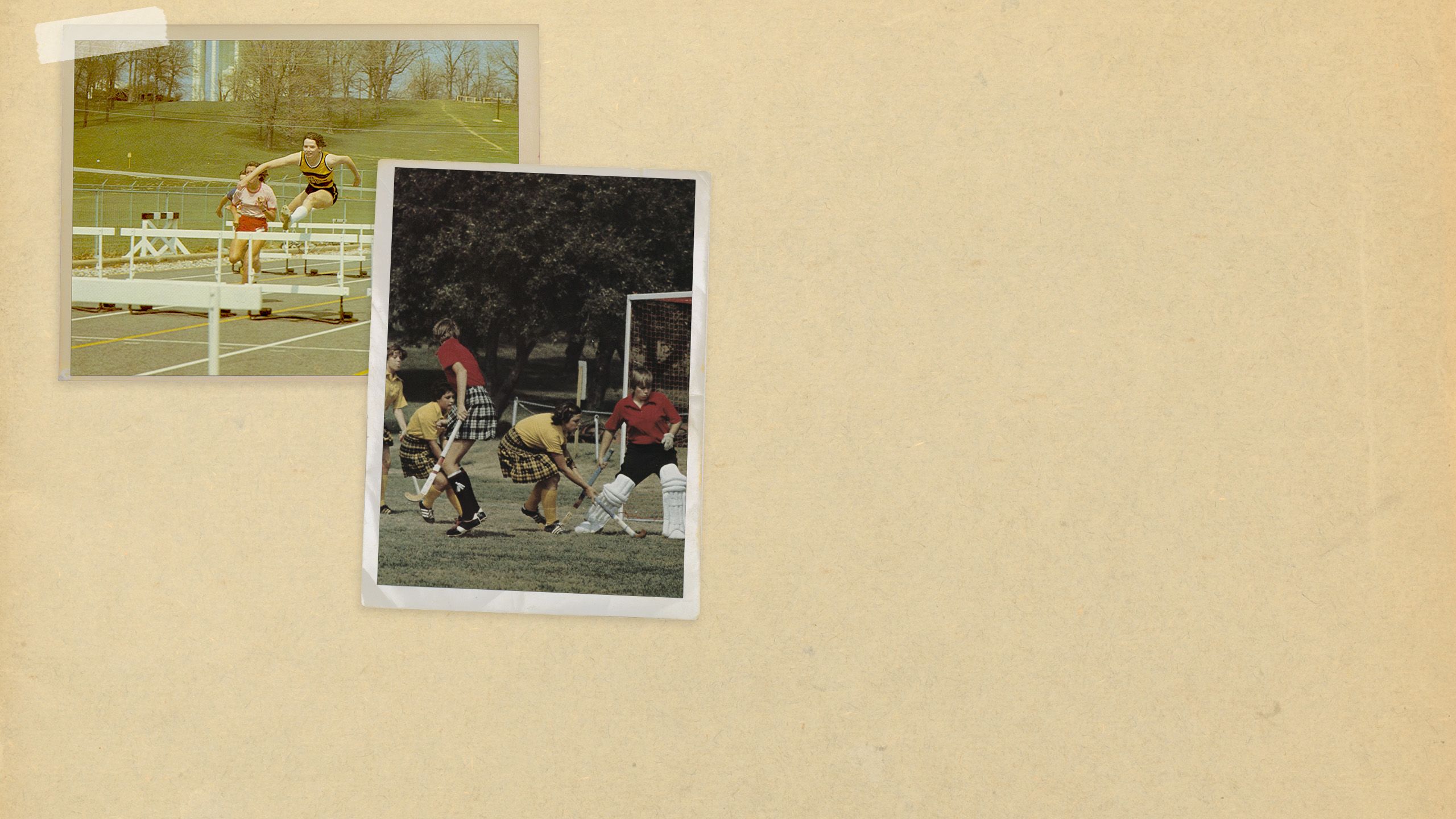

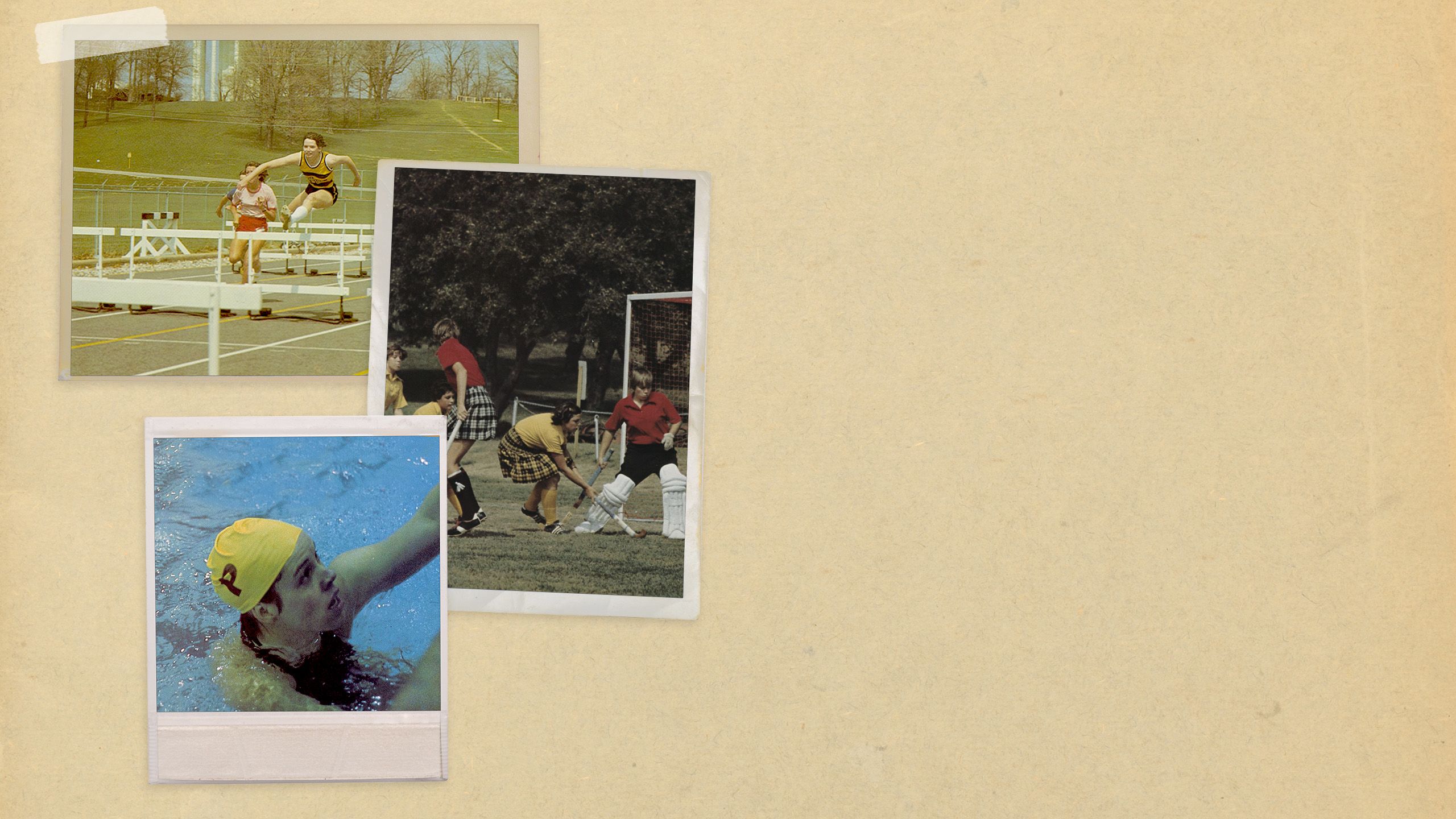

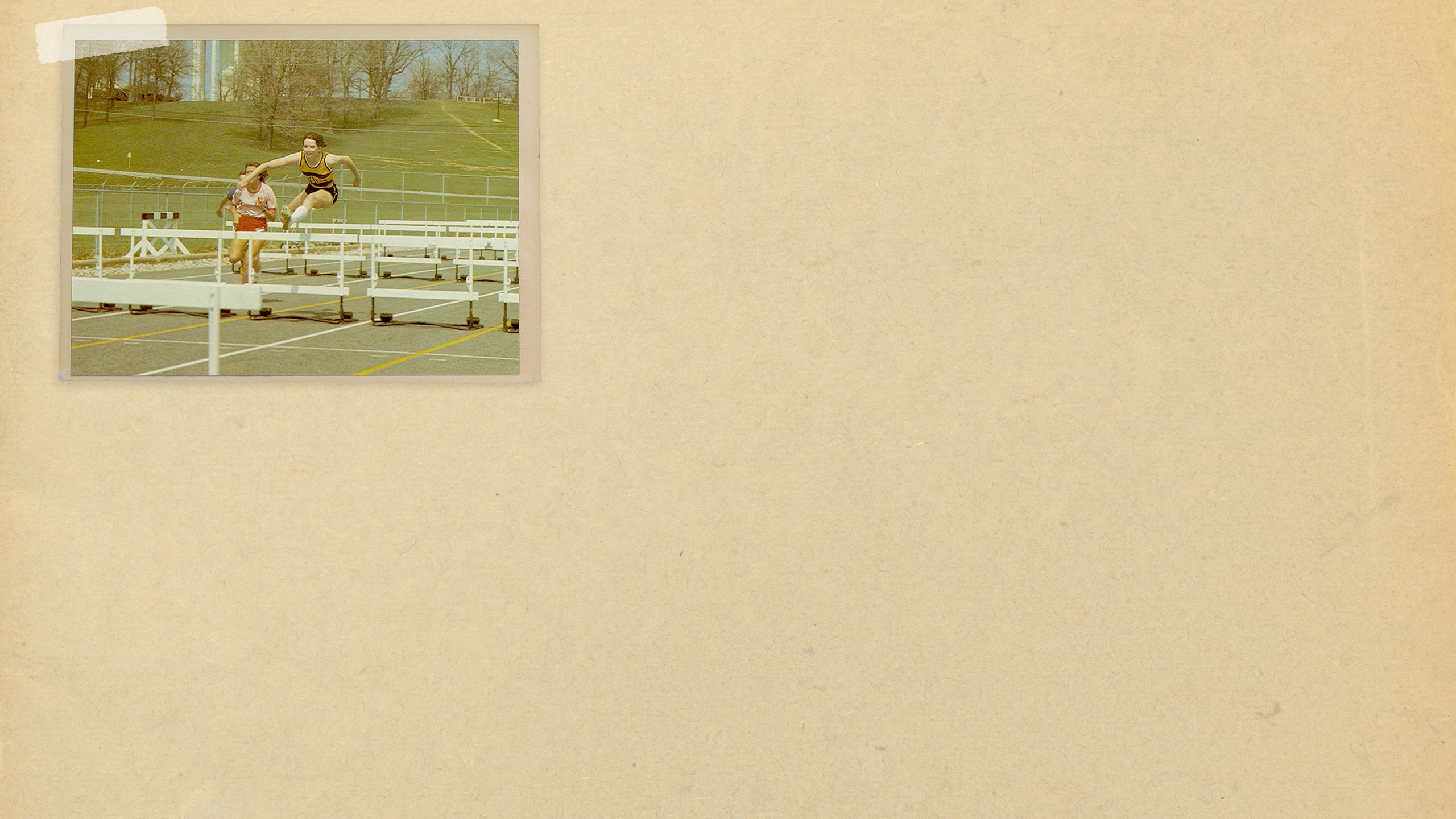

Purdue hired Carol Mertler as assistant athletics director in 1975 to oversee the development of the women’s varsity athletic program and appointed Sally Combs-Dunaway as director of public relations for women’s athletics. By 1976, women’s intercollegiate sports included field hockey, tennis, golf, basketball, volleyball, swimming, and track. Purdue hired Carol Dewey as its first women’s volleyball coach and Ruth Jones as its first women’s basketball coach, with other sports being coached by staff members or graduate students. In 1979, volleyball became Purdue’s first revenue-producing women’s sport. Women’s teams were governed by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women until the early 1980s when the NCAA took over the governance of women’s intercollegiate athletics and its national championship events.

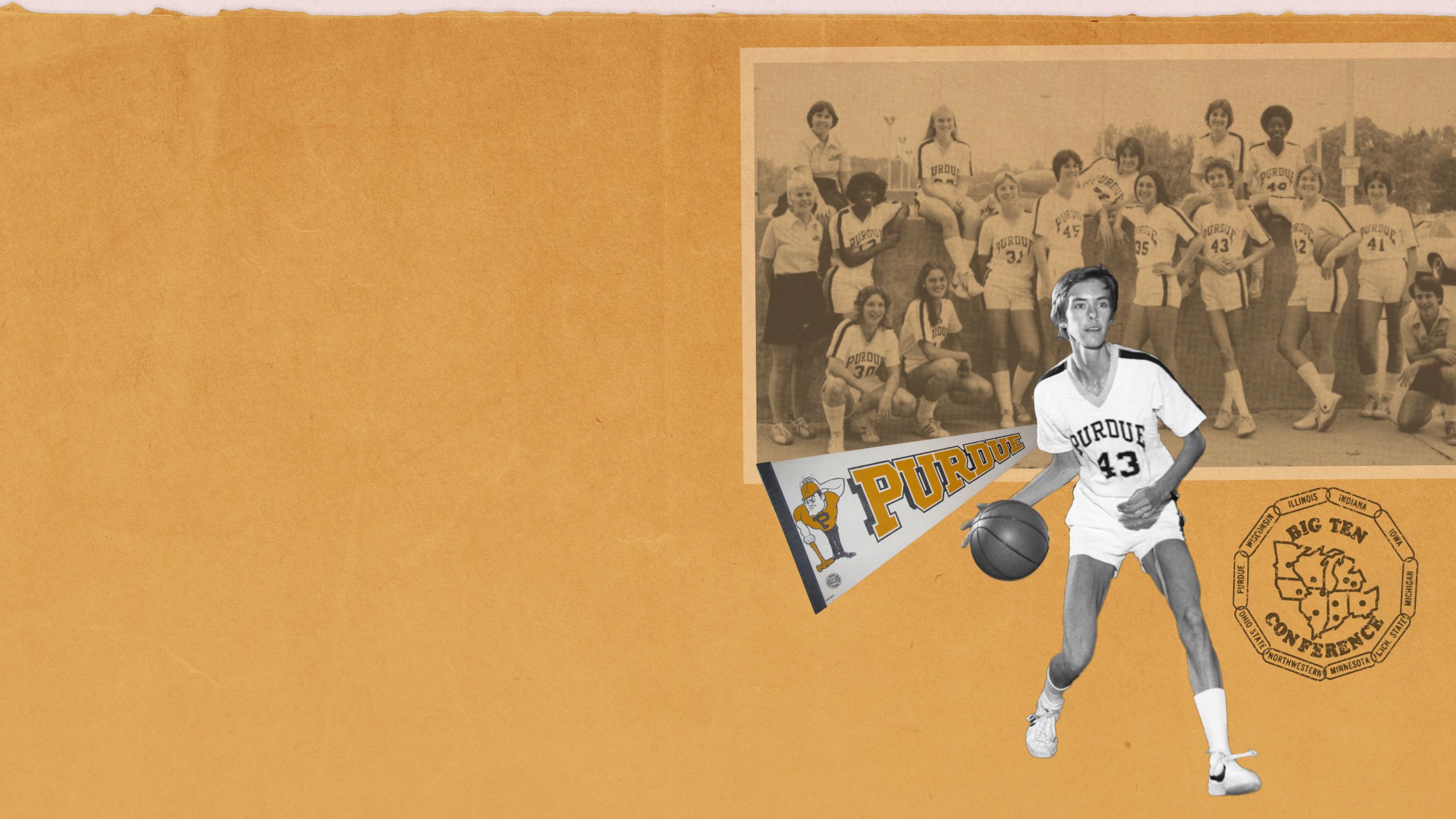

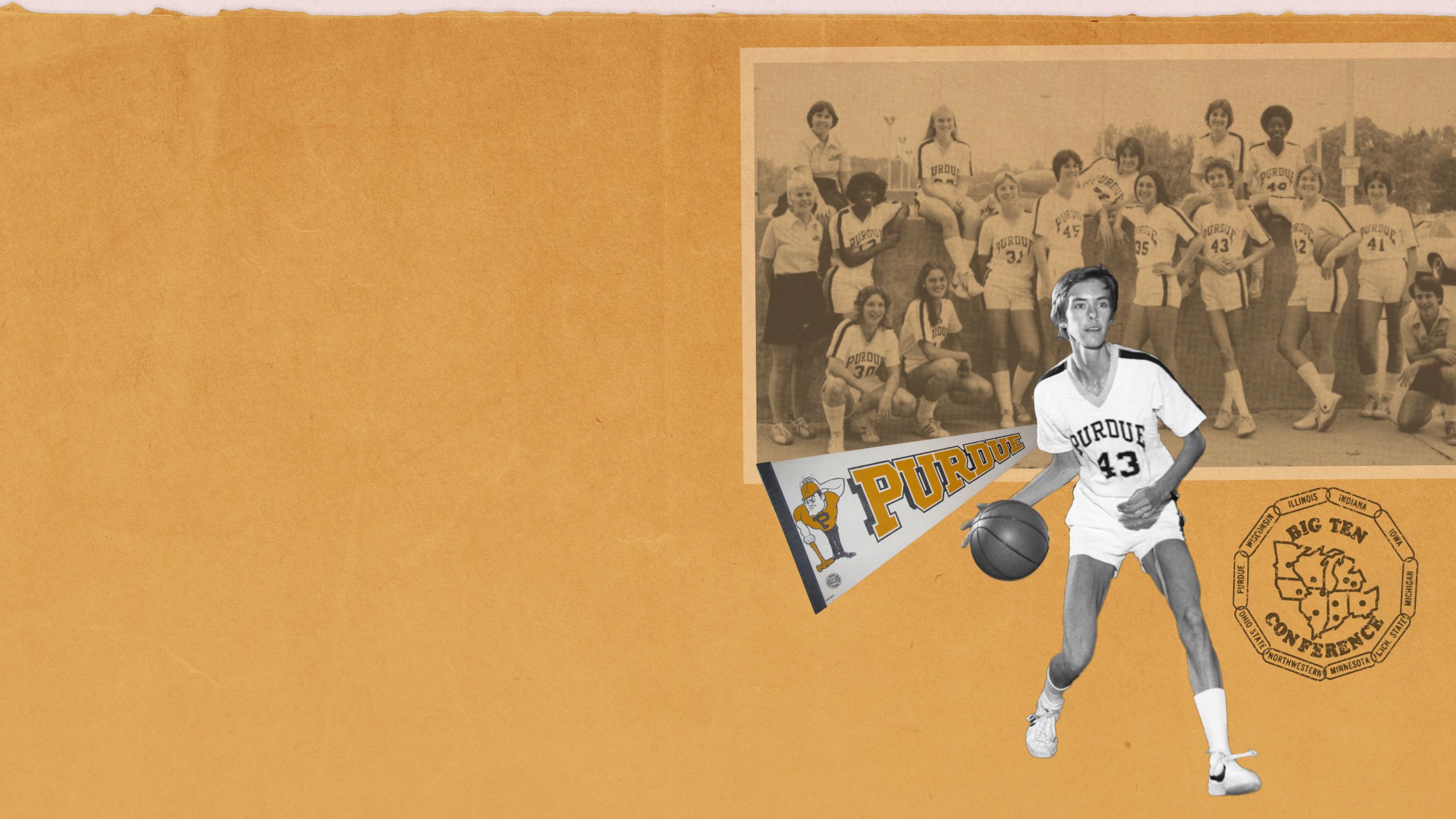

“Once Purdue’s athletics department took over administering women’s sports, we felt like we’d arrived,” says Ruley, who played both basketball and field hockey. “The amount of growth in women’s sports at Purdue in my four years was phenomenal. By my junior year, the women’s basketball team was playing in Mackey Arena; we had our tuition covered; and we were helping to recruit others.”

Ruley earned a bachelor’s degree in health, physical education, and recreation and holds the honor of scoring the first basket in Purdue women’s intercollegiate basketball history. She went on to become head women’s basketball coach at North Dakota State University, a position she held for 36 years.

“Thank God for Title IX. Who knows how long it would have taken for women to achieve equity in athletics without it?”

It wasn’t lost on her that money—or the threat of losing it—talked: The legislation presented a stark economic choice of either offering equal opportunities or losing federal funding, which propelled institutions nationwide to begin supporting women’s athletic endeavors.

As women became more vocal about the inequities they faced, doors began to open.

Purdue hired Carol Mertler as assistant athletics director in 1975 to oversee the development of the women’s varsity athletic program and appointed Sally Combs-Dunaway as director of public relations for women’s athletics. By 1976, women’s intercollegiate sports included field hockey, tennis, golf, basketball, volleyball, swimming, and track. Purdue hired Carol Dewey as its first women’s volleyball coach and Ruth Jones as its first women’s basketball coach, with other sports being coached by staff members or graduate students. In 1979, volleyball became Purdue’s first revenue-producing women’s sport. Women’s teams were governed by the Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women until the early 1980s when the NCAA took over the governance of women’s intercollegiate athletics and its national championship events.

“Once Purdue’s athletics department took over administering women’s sports, we felt like we’d arrived,” says Ruley, who played both basketball and field hockey. “The amount of growth in women’s sports at Purdue in my four years was phenomenal. By my junior year, the women’s basketball team was playing in Mackey Arena; we had our tuition covered; and we were helping to recruit others.”

Ruley earned a bachelor’s degree in health, physical education, and recreation and holds the honor of scoring the first basket in Purdue women’s intercollegiate basketball history. She went on to become head women’s basketball coach at North Dakota State University, a position she held for 36 years.

“Thank God for Title IX. Who knows how long it would have taken for women to achieve equity in athletics without it?”

It wasn’t lost on her that money—or the threat of losing it—talked: The legislation presented a stark economic choice of either offering equal opportunities or losing federal funding, which propelled institutions nationwide to begin supporting women’s athletic endeavors.

Celebrating Title IX’s Impact

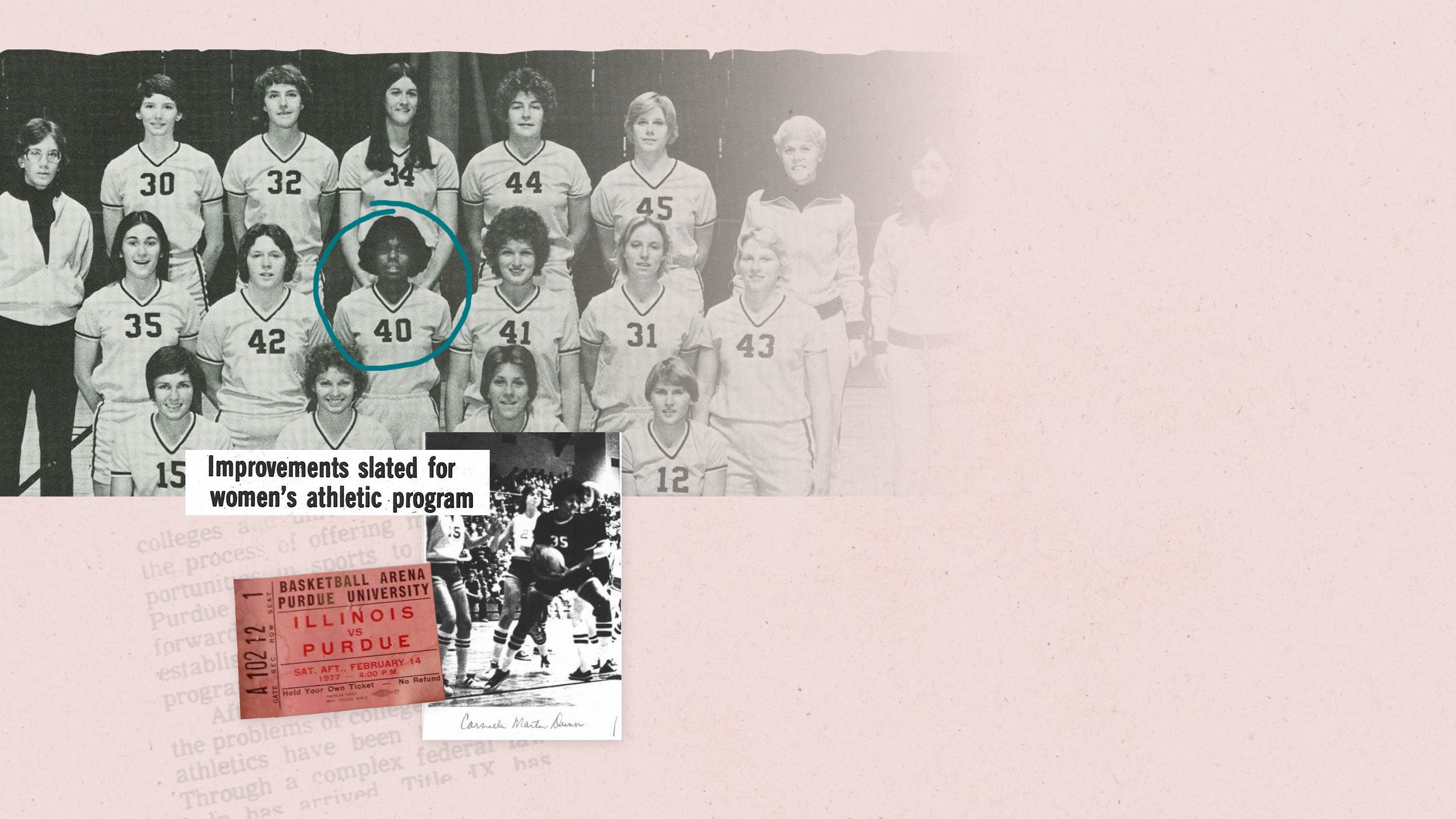

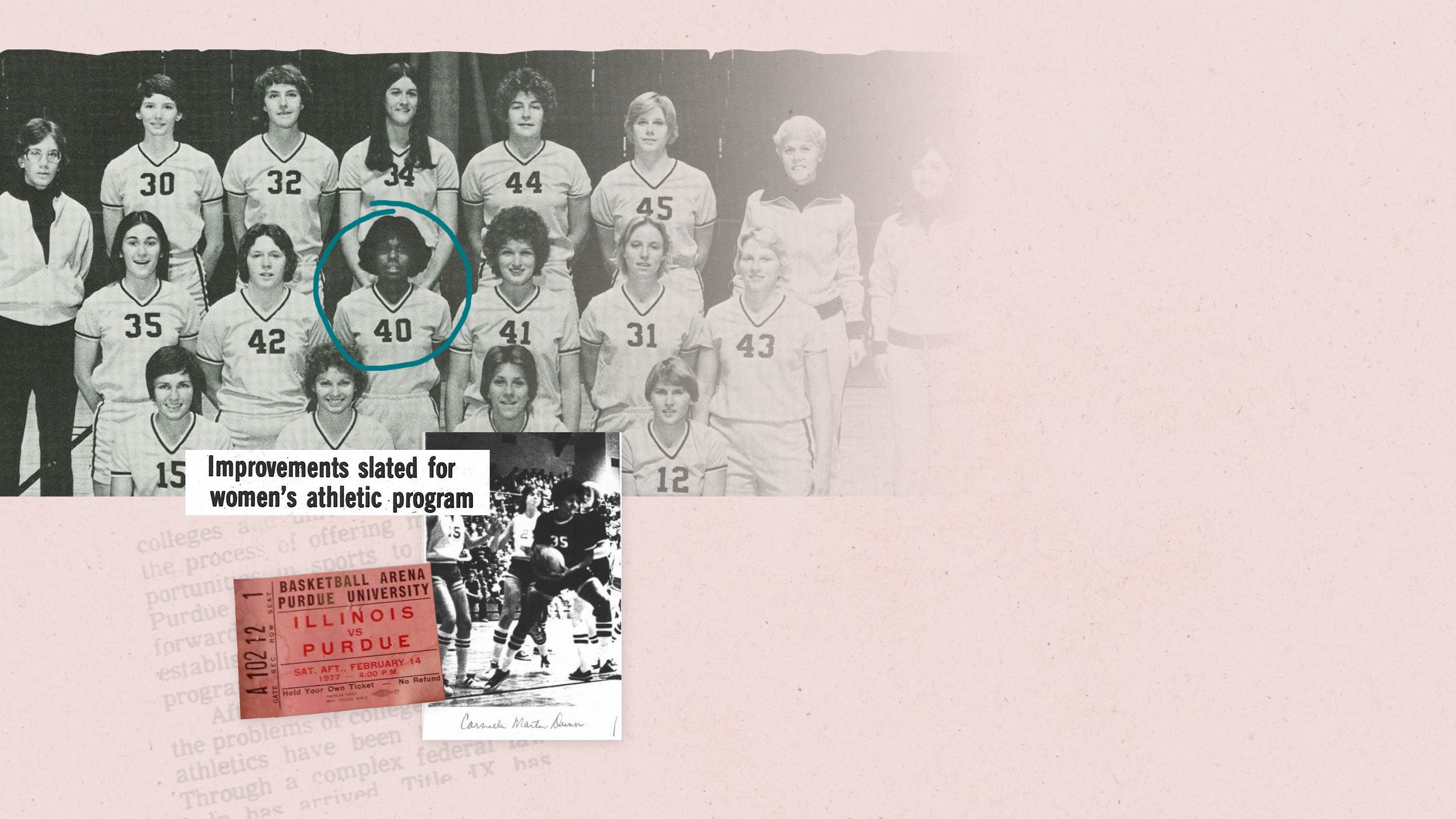

Carmella Martin Dunn (P’82) is familiar with breaking barriers. Before she walked on to Purdue’s women’s basketball team in the fall of 1976 as its first-ever Black player, she’d already made history. During her senior year at East Chicago Roosevelt High School, she got the first tip-off in the inaugural girls’ basketball state tournament at Hinkle Fieldhouse in Indianapolis.

“Even with my experience, nobody really looked at me for sports, so to be a walk-on at Purdue was incredible, and playing ball there was wonderful,” says Dunn, noting that the university wasn’t yet offering women athletic scholarships.

Dunn played through the 1977–78 season, when she gave up basketball to focus on her studies. She continued to be involved in athletics, however, by getting a referee license and refereeing men’s recreational games. Today, Dunn uses the interpersonal skills she learned in athletics at Purdue in her work as a pharmacist.

“Same as on the court, I have a team and have to deal with how each person’s different attitudes and personalities can affect that.”

In 2003, Dunn was one of the first class of women inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame. She insisted that her plaque reflect both her basketball career and her degree in pharmacy. “I want young women to know that you can be both a scholar and an athlete,” she says. “You don’t have to choose between the two.”

Celebrating Title IX’s Impact

Carmella Martin Dunn (P’82) is familiar with breaking barriers. Before she walked on to Purdue’s women’s basketball team in the fall of 1976 as its first-ever Black player, she’d already made history. During her senior year at East Chicago Roosevelt High School, she got the first tip-off in the inaugural girls’ basketball state tournament at Hinkle Fieldhouse in Indianapolis.

“Even with my experience, nobody really looked at me for sports, so to be a walk-on at Purdue was incredible, and playing ball there was wonderful,” says Dunn, noting that the university wasn’t yet offering women athletic scholarships.

Dunn played through the 1977–78 season, when she gave up basketball to focus on her studies. She continued to be involved in athletics, however, by getting a referee license and refereeing men’s recreational games. Today, Dunn uses the interpersonal skills she learned in athletics at Purdue in her work as a pharmacist.

“Same as on the court, I have a team and have to deal with how each person’s different attitudes and personalities can affect that.”

In 2003, Dunn was one of the first class of women inducted into the Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame. She insisted that her plaque reflect both her basketball career and her degree in pharmacy. “I want young women to know that you can be both a scholar and an athlete,” she says. “You don’t have to choose between the two.”

In the fall of 1977, as Dunn was starting her last year on the women’s basketball team, Beth Brooke (M’81, HDR’12) was just beginning her career as one of Purdue’s first class of female athletes to receive scholarship support.

“The program was in its infancy,” Brooke says. “We had to walk from our practice facility and locker rooms in Lambert Fieldhouse to play in Mackey Arena. It was apparent we weren’t the guys, but nonetheless, we had a great relationship with the men’s team and felt very supported. Our trappings weren’t the same, but so what? We were grateful to have a program.”

The budding women’s basketball program competed against other Big Ten universities as well as smaller universities like Western Kentucky and Central Michigan. “We were building a program, so we weren’t very good,” Ruley says. “Ruth Jones, our coach at the time, taught us to quit apologizing and to work at getting better.”

Brooke recalls that Jones worked the team hard. “She was wicked smart and a great role model,” Brooke says. “From day one, Purdue has run a first-class program.”

Brooke, who earned a bachelor’s degree in industrial management and computer science, says her athletic experience gave her a leg up in her chosen career fields of accounting and auditing, which in the early 1980s were male-dominated, conservative industries. “Sports taught me everything I needed to know to succeed in business,” she says.

Brooke recently retired as a global vice chair of Ernst & Young (EY), at which she was also the global sponsor of diversity and inclusion. She founded EY’s Women Athletes Business Network in 2013 with the goal of preparing young women to make an impact outside their sport. “Sports teach us discipline and focus and that losing is just feedback,” she says. “We learn to work harder, adjust, and change to get a better outcome.”

In 2017, the NCAA recognized Brooke’s efforts with its Theodore Roosevelt Award in honor of her work in modeling the ideals and purposes of collegiate athletics.

In the fall of 1977, as Dunn was starting her last year on the women’s basketball team, Beth Brooke (M’81, HDR’12) was just beginning her career as one of Purdue’s first class of female athletes to receive scholarship support.

“The program was in its infancy,” Brooke says. “We had to walk from our practice facility and locker rooms in Lambert Fieldhouse to play in Mackey Arena. It was apparent we weren’t the guys, but nonetheless, we had a great relationship with the men’s team and felt very supported. Our trappings weren’t the same, but so what? We were grateful to have a program.”

The budding women’s basketball program competed against other Big Ten universities as well as smaller universities like Western Kentucky and Central Michigan. “We were building a program, so we weren’t very good,” Ruley says. “Ruth Jones, our coach at the time, taught us to quit apologizing and to work at getting better.”

Brooke recalls that Jones worked the team hard. “She was wicked smart and a great role model,” Brooke says. “From day one, Purdue has run a first-class program.”

Brooke, who earned a bachelor’s degree in industrial management and computer science, says her athletic experience gave her a leg up in her chosen career fields of accounting and auditing, which in the early 1980s were male-dominated, conservative industries. “Sports taught me everything I needed to know to succeed in business,” she says.

Brooke recently retired as a global vice chair of Ernst & Young (EY), at which she was also the global sponsor of diversity and inclusion. She founded EY’s Women Athletes Business Network in 2013 with the goal of preparing young women to make an impact outside their sport. “Sports teach us discipline and focus and that losing is just feedback,” she says. “We learn to work harder, adjust, and change to get a better outcome.”

In 2017, the NCAA recognized Brooke’s efforts with its Theodore Roosevelt Award in honor of her work in modeling the ideals and purposes of collegiate athletics.

Nuances of Equity

The scope of Title IX is far-reaching, playing a role in academics, athletics, and the handling of sexual violence at federally funded educational institutions. It was coauthored by former U.S. senator Birch Bayh (A’51, HDR A’65) of Indiana, who played baseball at Purdue and competed as a Golden Gloves boxer. He died in 2019, having lived to see the impact of Title IX on higher education, once calling it the single greatest achievement of his political career.

Though Title IX doesn’t mention athletics or sports, the impact the legislation had on girls’ and women’s sports has been immense in the 50 years since its passing. When Title IX first became law, the differences among men’s and women’s sports was vast; today, the gap is much narrower. At Purdue, both men and women compete in 10 varsity sports each. There are currently more than 240 women competing in at least one varsity sport at Purdue, with more than 200,000 women competing on NCAA teams nationwide. Purdue has improved opportunities, funding, and facilities to help give female athletes a similar experience to their male counterparts.

“Once Purdue made the decision in 1974 to move the administration of women’s sports under the athletics department, the university fully committed to supporting us,” Ruley says.

“We went from trying out in our own clothing to getting practice gear, practice time, coaching, and more. Once we started receiving scholarships, we thought we had died and gone to heaven.”

Everyone Gained

Title IX didn’t just help women, says Nancy Cross (MS HHS’78), who coached women’s field hockey as a graduate student and became Purdue’s senior associate athletics director for development and sports and the senior woman administrator before retiring in June. Parity across all genders in athletics continues to be Purdue’s goal, she says.

“Title IX raised the level of resources for all intercollegiate athletics, regardless of gender,” Cross says. “Once we took the gender discussion off the table and made decisions about what was best for all of our student-athletes, there was a shift to embracing the spirit of Title IX.” She credits the hiring of Morgan Burke (M’73, MS M’75) as athletic director in 1993 with leading that shift. “He taught us that every decision needs to reflect what’s fair to every athlete, regardless of whether they play golf or football.”

Cross, now the director of campaigns for the Purdue for Life Foundation, also notes that Purdue supports an equitable allocation of resources in athletics. Financial support that goes to the John Purdue Club helps cover the tuition, room and board, books, and academic-support costs of Purdue’s more than 500 student-athletes.

“The women’s programs started in the 1970s, so their alumni base is much smaller than the men’s, with programs dating back more than 100 years,” Cross says. “By not allowing restricted donations, we have leveled the playing field with regard to resource allocation.”

Nuances of Equity

The scope of Title IX is far-reaching, playing a role in academics, athletics, and the handling of sexual violence at federally funded educational institutions. It was coauthored by former U.S. senator Birch Bayh (A’51, HDR A’65) of Indiana, who played baseball at Purdue and competed as a Golden Gloves boxer. He died in 2019, having lived to see the impact of Title IX on higher education, once calling it the single greatest achievement of his political career.

Though Title IX doesn’t mention athletics or sports, the impact the legislation had on girls’ and women’s sports has been immense in the 50 years since its passing. When Title IX first became law, the differences among men’s and women’s sports was vast; today, the gap is much narrower. At Purdue, both men and women compete in 10 varsity sports each. There are currently more than 240 women competing in at least one varsity sport at Purdue, with more than 200,000 women competing on NCAA teams nationwide. Purdue has improved opportunities, funding, and facilities to help give female athletes a similar experience to their male counterparts.

“Once Purdue made the decision in 1974 to move the administration of women’s sports under the athletics department, the university fully committed to supporting us,” Ruley says.

“We went from trying out in our own clothing to getting practice gear, practice time, coaching, and more. Once we started receiving scholarships, we thought we had died and gone to heaven.”

Everyone Gained

Title IX didn’t just help women, says Nancy Cross (MS HHS’78), who coached women’s field hockey as a graduate student and became Purdue’s senior associate athletics director for development and sports and the senior woman administrator before retiring in June. Parity across all genders in athletics continues to be Purdue’s goal, she says.

“Title IX raised the level of resources for all intercollegiate athletics, regardless of gender,” Cross says. “Once we took the gender discussion off the table and made decisions about what was best for all of our student-athletes, there was a shift to embracing the spirit of Title IX.” She credits the hiring of Morgan Burke (M’73, MS M’75) as athletic director in 1993 with leading that shift. “He taught us that every decision needs to reflect what’s fair to every athlete, regardless of whether they play golf or football.”

Cross, now the director of campaigns for the Purdue for Life Foundation, also notes that Purdue supports an equitable allocation of resources in athletics. Financial support that goes to the John Purdue Club helps cover the tuition, room and board, books, and academic-support costs of Purdue’s more than 500 student-athletes.

“The women’s programs started in the 1970s, so their alumni base is much smaller than the men’s, with programs dating back more than 100 years,” Cross says. “By not allowing restricted donations, we have leveled the playing field with regard to resource allocation.”

Continued Push for Equity

Cheryl Cooky—professor of American studies and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies—teaches courses that examine forms of gender-based inequality in sports, giving Purdue students the opportunity to study Title IX’s impact and gain an applied understanding of the legislation in the athletics realm.

Cooky’s research examines how gender shapes cultural meaning, experiences, and societal structures in the context of sports. She has worked with the Women’s Sports Foundation in developing evidence-based policies that address the specific needs of girls in sports. She is the coauthor of the foundation’s report on gender equity, titled Chasing Equity: The Triumphs, Challenges and Opportunities in Sports for Girls and Women.

“In its 50 years, Title IX has shifted the cultural expectations around what women can do in the athletic sphere, and that impact is certainly worthy of celebration,” Cooky says. “But there remain inequities that we still need to address to achieve full equality.” She notes, for example, the NCAA’s 2021 reported underinvestment in its women’s basketball tournament; discrepancies in media coverage of men’s and women’s sports; and the prevalence of men coaching women’s intercollegiate teams.

“It’s important for everyone to understand why gender equality matters, why it’s important, what’s at stake, and why we should care,” Cooky says.

“The impact of Title IX has been enormous, but our work is not complete. Hopefully in another 50 years, we can say, ‘Now we’re done.’”

Continued Push for Equity

Cheryl Cooky—professor of American studies and women’s, gender, and sexuality studies—teaches courses that examine forms of gender-based inequality in sports, giving Purdue students the opportunity to study Title IX’s impact and gain an applied understanding of the legislation in the athletics realm.

Cooky’s research examines how gender shapes cultural meaning, experiences, and societal structures in the context of sports. She has worked with the Women’s Sports Foundation in developing evidence-based policies that address the specific needs of girls in sports. She is the coauthor of the foundation’s report on gender equity, titled Chasing Equity: The Triumphs, Challenges and Opportunities in Sports for Girls and Women.

“In its 50 years, Title IX has shifted the cultural expectations around what women can do in the athletic sphere, and that impact is certainly worthy of celebration,” Cooky says. “But there remain inequities that we still need to address to achieve full equality.” She notes, for example, the NCAA’s 2021 reported underinvestment in its women’s basketball tournament; discrepancies in media coverage of men’s and women’s sports; and the prevalence of men coaching women’s intercollegiate teams.

“It’s important for everyone to understand why gender equality matters, why it’s important, what’s at stake, and why we should care,” Cooky says.

“The impact of Title IX has been enormous, but our work is not complete. Hopefully in another 50 years, we can say, ‘Now we’re done.’”

FOSTER PERSISTENCE!

Help support women’s athletics at Purdue.

Read more stories from this issue of Purdue Alumnus magazine.

View a text-only version of this story.