// By Angie Klink (LA’81)

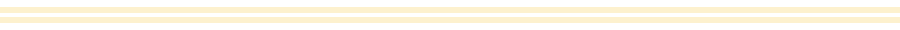

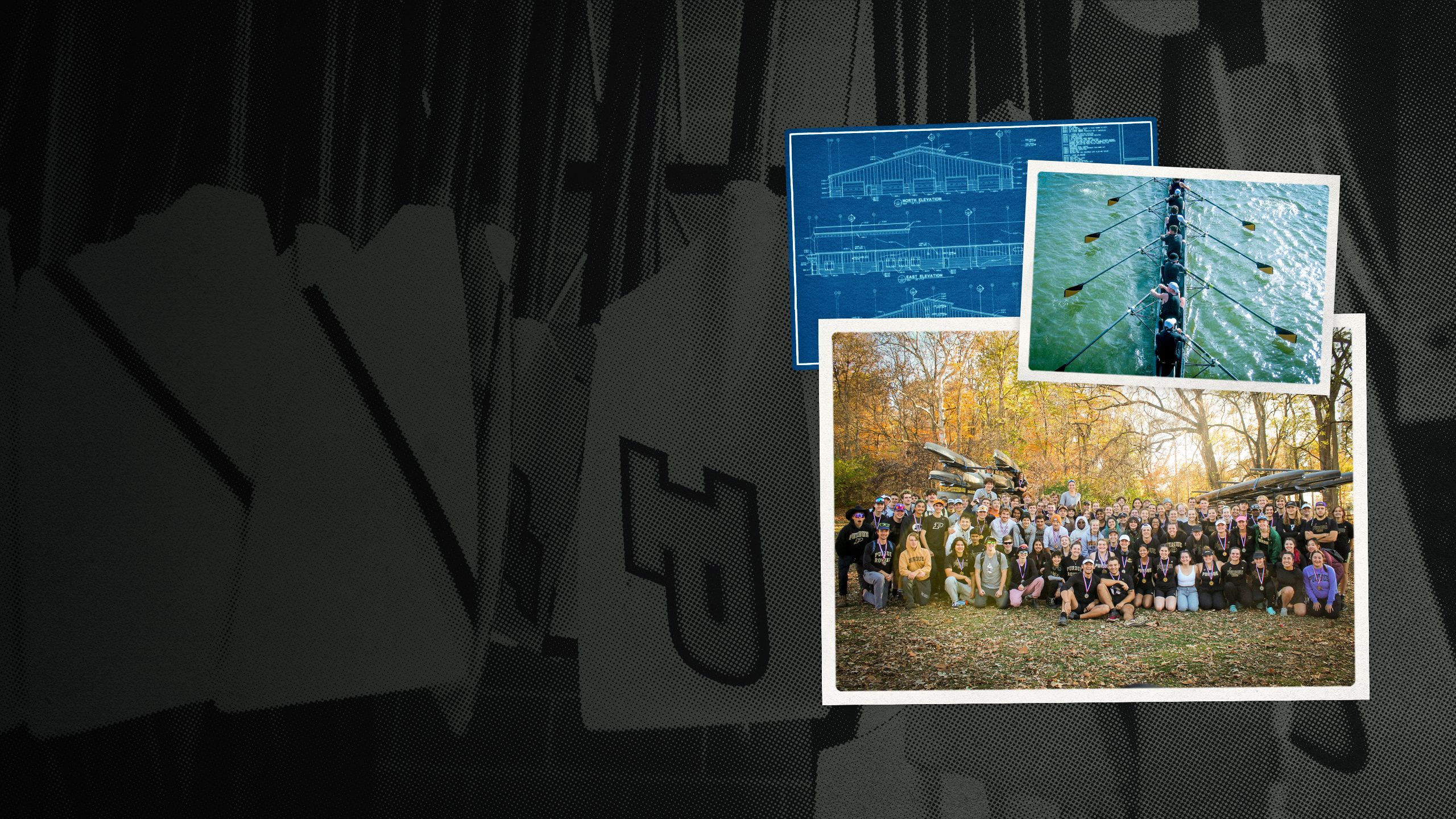

In a shell the color of saffron, eight rowers become one.

Single in mind, muscle, and mastery, each, with feet strapped, grasps an oar, pushes with strong legs, and slides rearward on a gliding seat.

The boat moves forward, a blade in the water.

Oars click, click, click.

A race is five to seven minutes long, covering 2,000 meters. Only the coxswain at the stern sees the finish line—the other members sit backward. The coxswain acts as the eyes of the team, steering around obstacles, maintaining a safe distance between other crews, and navigating turns. The stroke rower provides the rhythm while the coxswain dictates cadence and motivation as the rowers’ legs and lungs burn.

During practices, the Purdue shell gracefully slices the Wabash River under bridges and past homes, businesses, and railroad tracks buffered by pin oaks and sugar maples. A bald eagle flies overhead. This is the romance of rowing. It’s what spectators see as they drive across a Tippecanoe County bridge or stand at the river bank, not fully grasping that rowing is perhaps the most grueling of team sports.

“Rowing at the higher levels looks effortless because there’s no wasted energy, and yet, it’s all the effort you could possibly throw at it,” says Nathan Walker (LA’05), former Purdue Crew head men’s coach and director of rowing programs. “When you’re doing it right, you get blisters and calluses all over your hands. You’re burning from oxygen debt. It’s a brutally difficult sport.”

Walker, a Crew alumnus, succeeded his coach David Kucik who arrived on campus in 1995 and retired in 2021.

“I came from two intercollegiate programs previously and was familiar with how to prepare for intercollegiate competitions,” Kucik says. “Coming to Purdue, I wasn’t sure what I was getting myself into, but I found very quickly that the club athlete is equal to the task that would be put before an intercollegiate athlete. They also strive very well academically.”

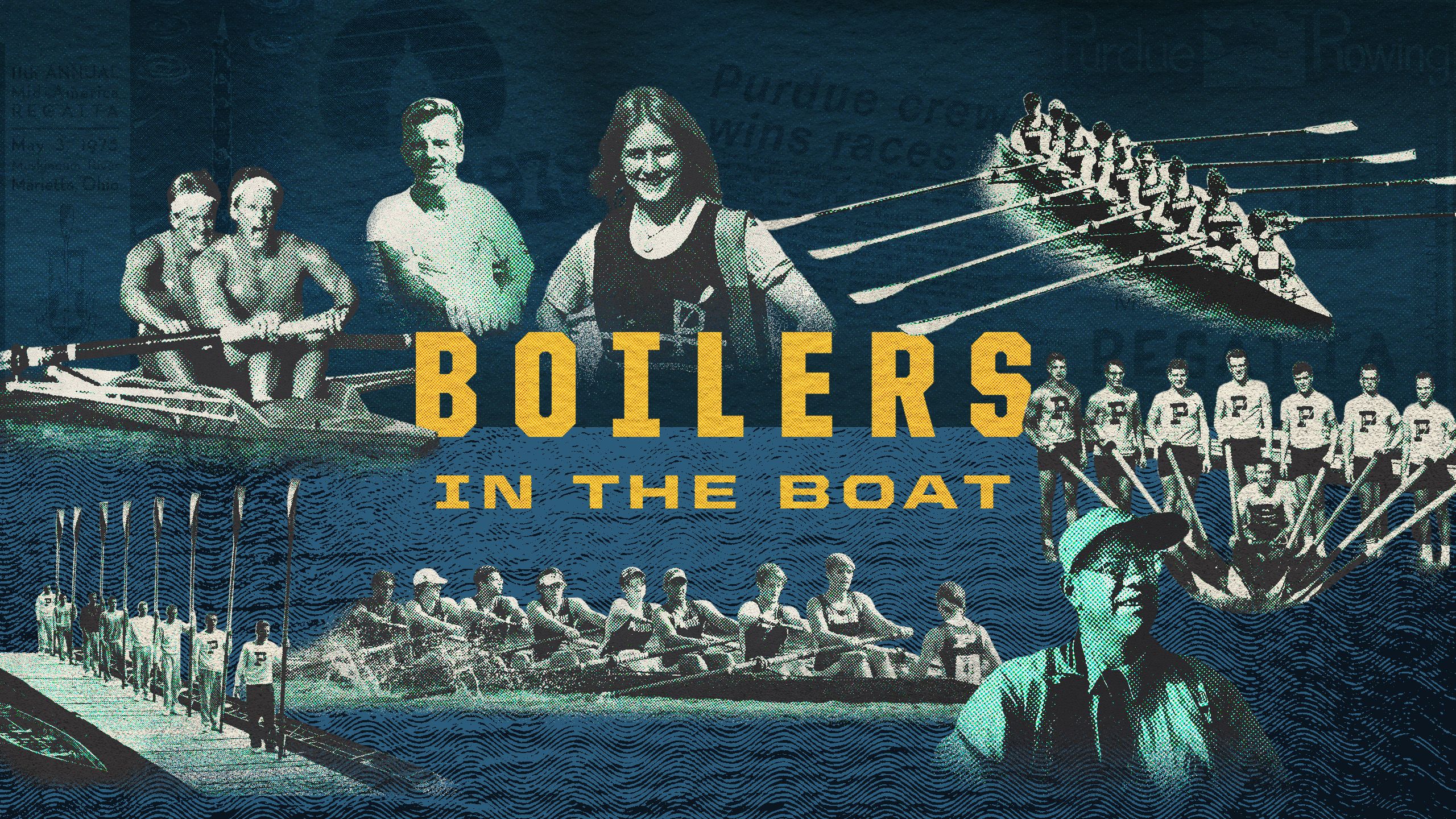

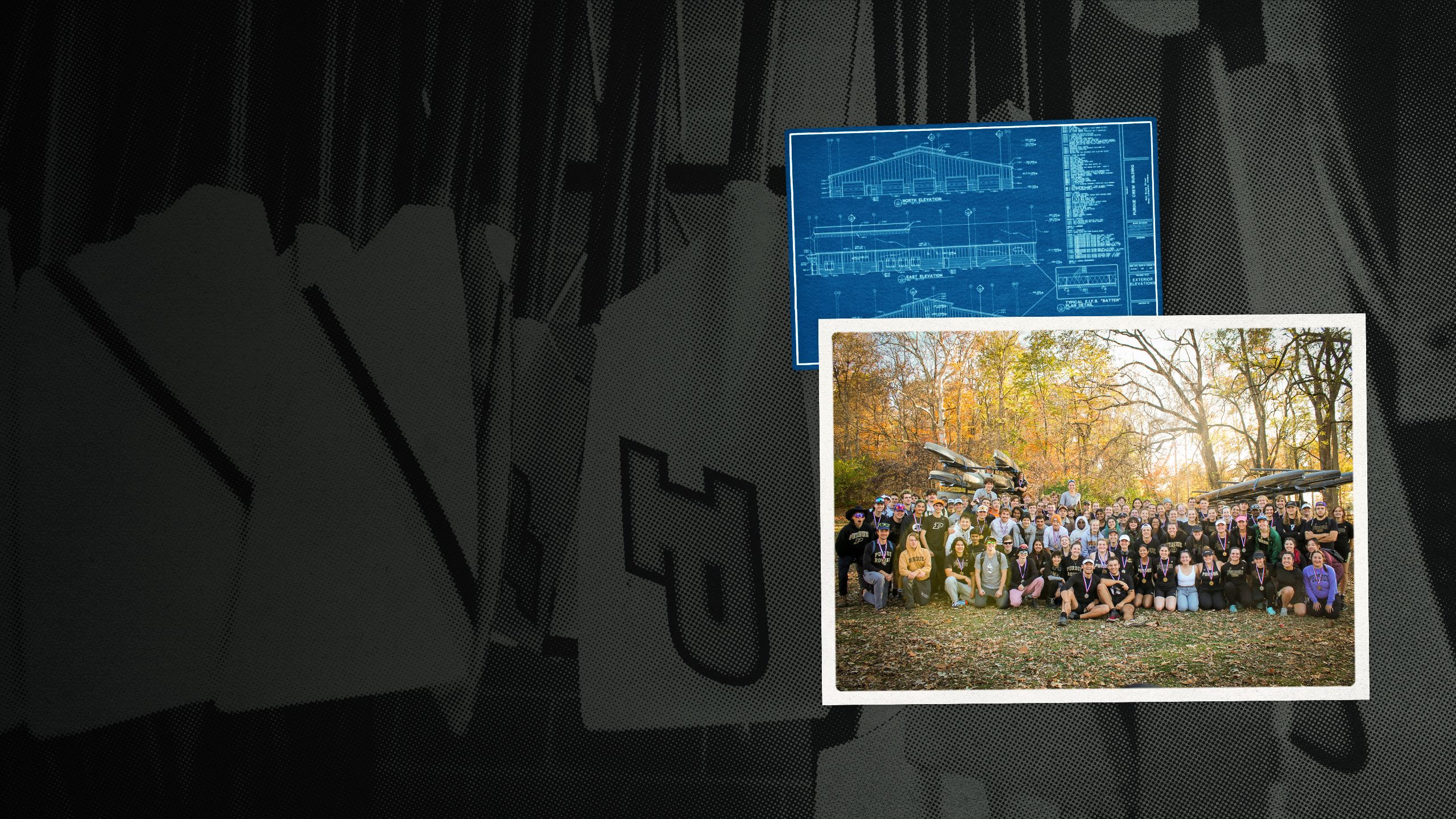

Approximately 140 students row on the men’s and women’s varsity and novice teams in seven to 10 races per year as part of the Southern Intercollegiate Rowing Association. They practice six days a week on the Wabash River—under sun-drenched skies, eerie fog, or pelting sleet. Practice is indoors only when the weather is unsafe, during lightning or high winds.

In the winter, when the Wabash is thick with ice, they head indoors to ergometers or “ergs,” rowing machines with monitors for coaches to gauge prowess and place similarly skilled rowers together to become a symphony of motion inside a shell. Rowers strive to perfect their stroke individually yet synchronize as a team to move the 211-pound boat seamlessly through the water. An eight-person shell is 58 feet long and just wide enough for a rower to sit.

Crew is a club sport “with an asterisk.” Depending upon skills and the number of races, rowers can pay between just under $2,000 to more than $3,500 annually. However, the team now benefits from two full-time coaches paid by Purdue. These paid positions are thanks to the efforts of former coaches and alumni who extolled the value of the student-athlete experience—including the leadership opportunities offered to team members—to university administrators.

To keep the program afloat, students participate in fundraisers and philanthropy, such as Rent-a-Rower, where community members pay students to perform odd jobs, and the annual Row-a-Thon benefiting the team and Lafayette Urban Ministries. There are no scholarships.

“Students bear the brunt of most of the operating costs outside of alumni giving and endowment support that we’ve built over time,” Walker says. “They’re on the water in early March, and it’s cold and unforgiving. Students pay to do that repeatedly while also perhaps holding an officer position and putting in 20 hours a week to make sure the crew can function. The people who are drawn to the sport are incredibly driven, and they push themselves beyond any reasonable amount to succeed. It’s unforgiving in the best way possible, because it’s the most objective, honest measure of where you stand when you get to the race and you’re 10 seconds back.”

A race is five to seven minutes long, covering 2,000 meters. Only the coxswain at the stern sees the finish line—the other members sit backward. The coxswain acts as the eyes of the team, steering around obstacles, maintaining a safe distance between other crews, and navigating turns. The stroke rower provides the rhythm while the coxswain dictates cadence and motivation as the rowers’ legs and lungs burn.

During practices, the Purdue shell gracefully slices the Wabash River under bridges and past homes, businesses, and railroad tracks buffered by pin oaks and sugar maples. A bald eagle flies overhead. This is the romance of rowing. It’s what spectators see as they drive across a Tippecanoe County bridge or stand at the river bank, not fully grasping that rowing is perhaps the most grueling of team sports.

“Rowing at the higher levels looks effortless because there’s no wasted energy, and yet, it’s all the effort you could possibly throw at it,” says Nathan Walker (LA’05), former Purdue Crew head men’s coach and director of rowing programs. “When you’re doing it right, you get blisters and calluses all over your hands. You’re burning from oxygen debt. It’s a brutally difficult sport.”

Walker, a Crew alumnus, succeeded his coach David Kucik who arrived on campus in 1995 and retired in 2021.

“I came from two intercollegiate programs previously and was familiar with how to prepare for intercollegiate competitions,” Kucik says. “Coming to Purdue, I wasn’t sure what I was getting myself into, but I found very quickly that the club athlete is equal to the task that would be put before an intercollegiate athlete. They also strive very well academically.”

Approximately 140 students row on the men’s and women’s varsity and novice teams in seven to 10 races per year as part of the Southern Intercollegiate Rowing Association. They practice six days a week on the Wabash River—under sun-drenched skies, eerie fog, or pelting sleet. Practice is indoors only when the weather is unsafe, during lightning or high winds.

In the winter, when the Wabash is thick with ice, they head indoors to ergometers or “ergs,” rowing machines with monitors for coaches to gauge prowess and place similarly skilled rowers together to become a symphony of motion inside a shell. Rowers strive to perfect their stroke individually yet synchronize as a team to move the 211-pound boat seamlessly through the water. An eight-person shell is 58 feet long and just wide enough for a rower to sit.

Crew is a club sport “with an asterisk.” Depending upon skills and the number of races, rowers can pay between just under $2,000 to more than $3,500 annually. However, the team now benefits from two full-time coaches paid by Purdue. These paid positions are thanks to the efforts of former coaches and alumni who extolled the value of the student-athlete experience—including the leadership opportunities offered to team members—to university administrators.

To keep the program afloat, students participate in fundraisers and philanthropy, such as Rent-a-Rower, where community members pay students to perform odd jobs, and the annual Row-a-Thon benefiting the team and Lafayette Urban Ministries. There are no scholarships.

“Students bear the brunt of most of the operating costs outside of alumni giving and endowment support that we’ve built over time,” Walker says. “They’re on the water in early March, and it’s cold and unforgiving. Students pay to do that repeatedly while also perhaps holding an officer position and putting in 20 hours a week to make sure the crew can function. The people who are drawn to the sport are incredibly driven, and they push themselves beyond any reasonable amount to succeed. It’s unforgiving in the best way possible, because it’s the most objective, honest measure of where you stand when you get to the race and you’re 10 seconds back.”

Purdue crew’s love for the unforgiving took root 75 years ago.

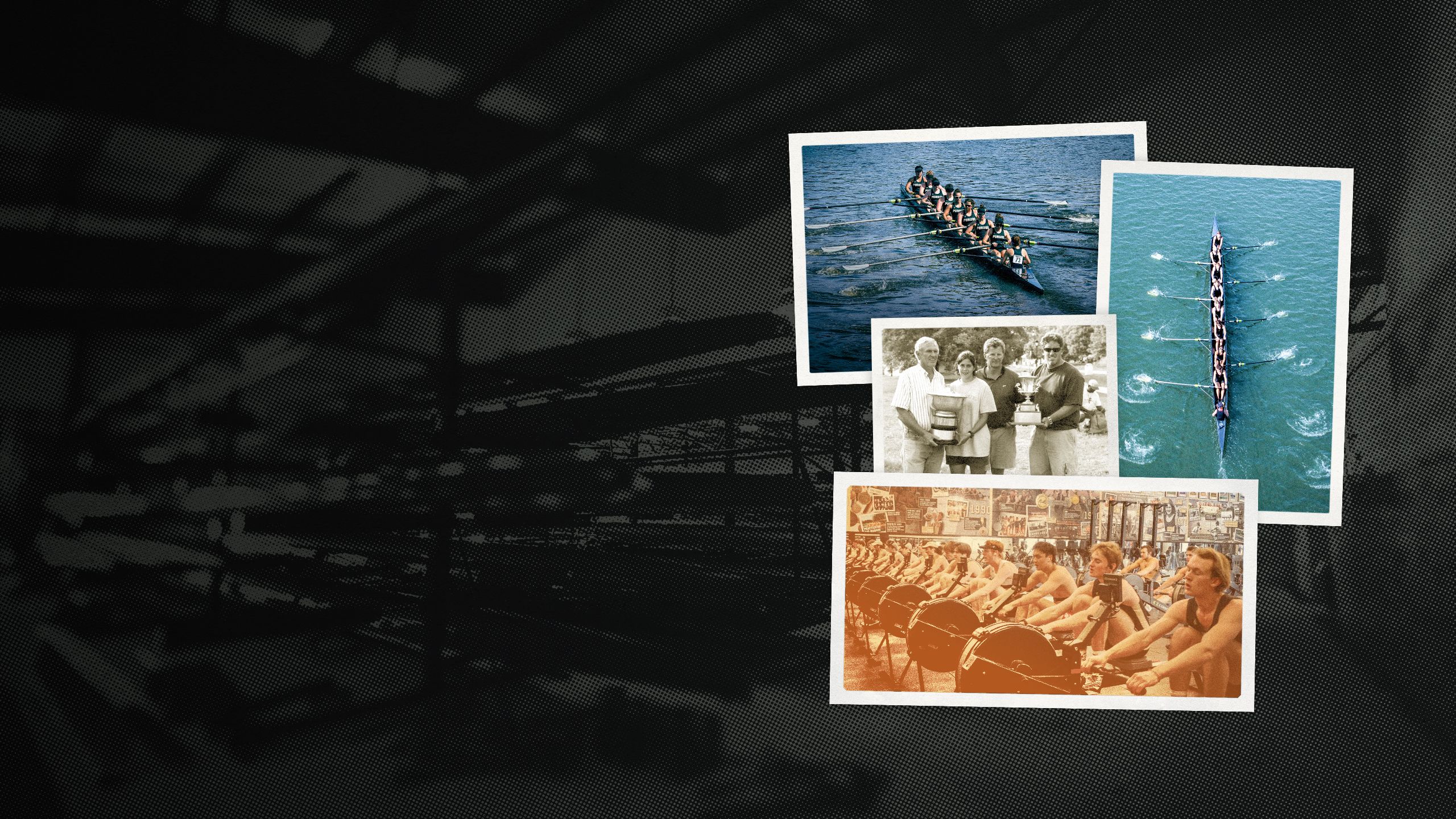

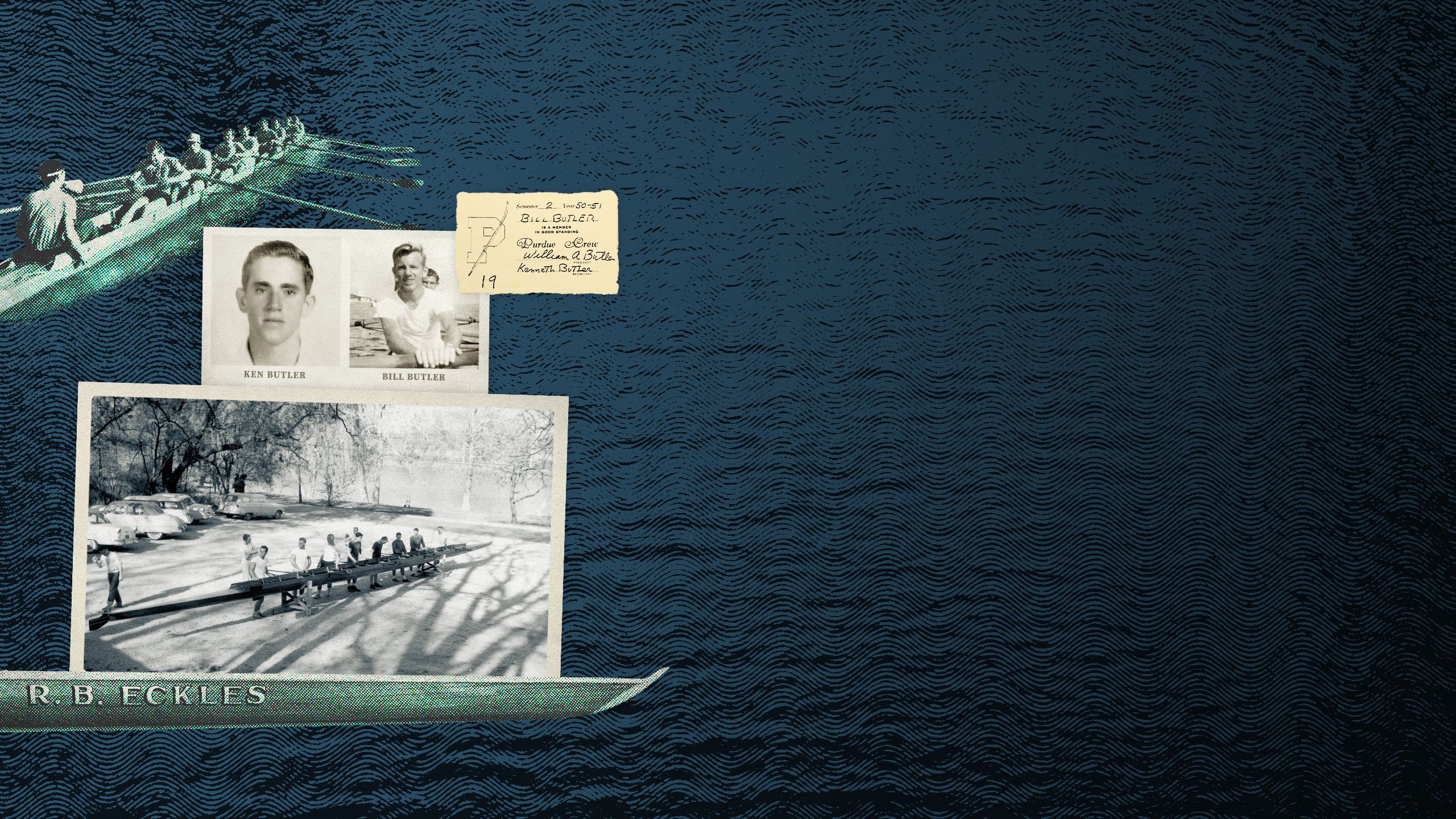

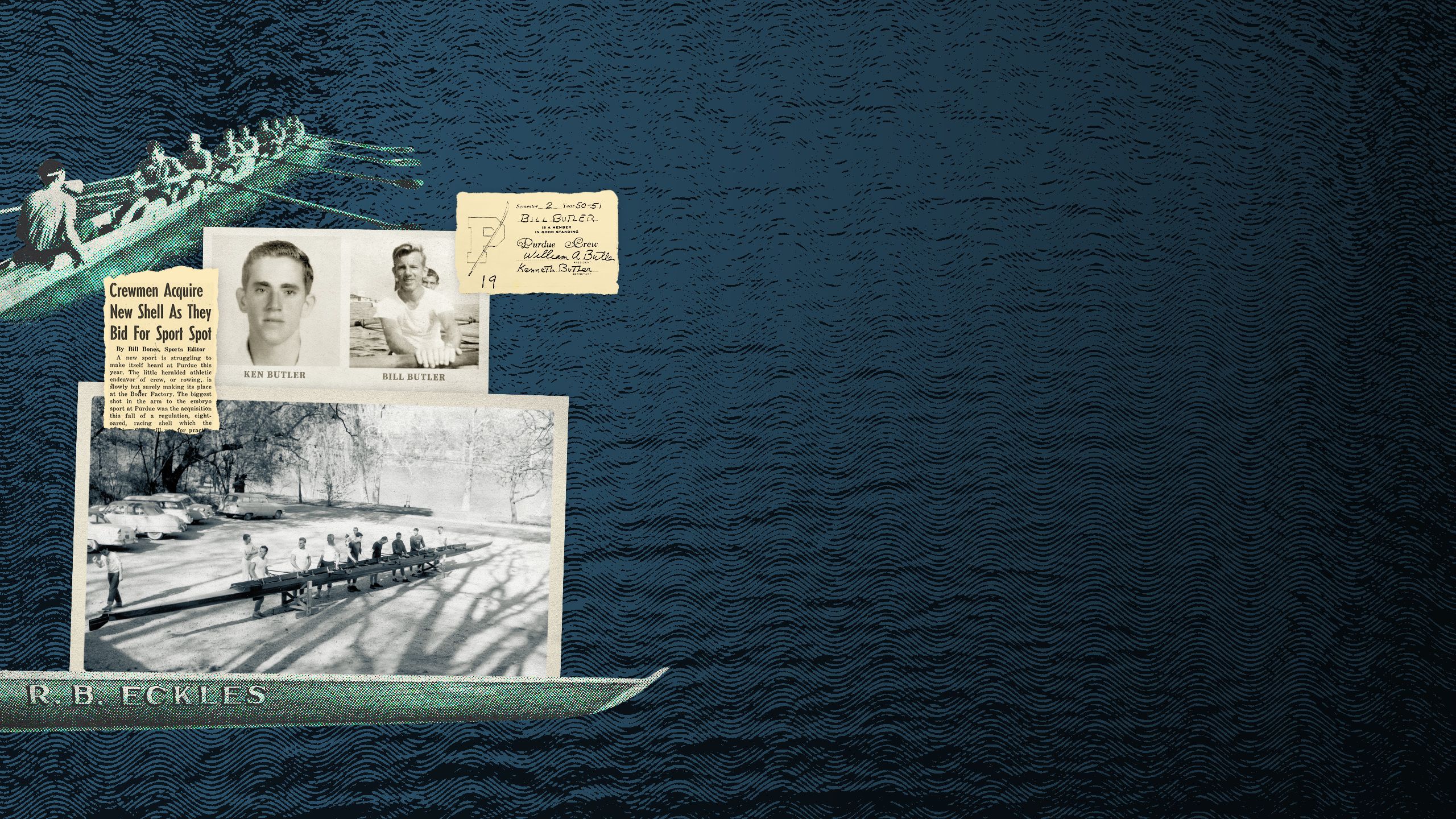

The team was founded by Cuban-born brothers Ken (S’53) and Bill (ECE’51) Butler, rowers who were distant cousins of Winthrop Stone, Purdue’s president from 1900 to 1921.

In the summer of 1949, Ken rowed for the undefeated Havana Biltmore program. That fall, he came to Purdue, joining his brother who was already a student. Ken longed to continue rowing, and the Wabash River beckoned.

In early 1950, Bill, spurred by Ken, placed a series of letters in the Purdue Exponent titled “The Sport of Rowing.” As intended, the letters enticed students’ interest. A meeting was held in the Purdue Memorial Union to organize a rowing team.

When the University of Wisconsin heard that Purdue wanted to start a crew but could not afford a boat, they donated their mothballed, eight-oared, canvas-covered shell. Nearly rotted, it became Purdue Crew’s pride and joy.

M.L. Clevett, head of Purdue’s Intramural Department, facilitated the club’s formation, locating land loaned by the Lincoln Lodge (later renamed Merou Grotto and demolished in 2019) on North River Road for the team to build a dock and boathouse. Over the years, Crew received steadfast support from Purdue’s Recreational Sports Division, now known as Recreation & Wellness.

The seven-member club formulated a constitution, and rowing machines were set up at Lambert Fieldhouse. Norwegian student Hakon Refsum (ME’52) was the first official coach.

Purdue’s inaugural race occurred on June 2, 1951, at the Culver Military Academy with Ken Butler as coxswain.

The Exponent reported, “The race was close at halfway, with Purdue up by a bow length. Disaster struck Purdue when the crews hit rough water caused by a patch of unprotected wind. Rowing errors ensued, described as ‘catching crabs,’ and Culver pulled ahead in the choppy water for the win.”

The following year, Purdue received a used cedar shell from Harvard, procured by history professor Robert B. Eckles, a Harvard graduate and the team’s first faculty advisor. With two boats, the members could arrange their first racing schedule. In his book Purdue Crew—20 Years of Rowing: 1949–1969, former coxswain Bruce Blackwell (M’64) recalled that the good-natured Eckles made the team feel important. Yet, “the school and its body barely knew we were on the river.”

The first crew race between Big Ten schools (and the only Big Ten rowing teams at the time) occurred on May 3, 1952, when Purdue rowed unsuccessfully against Wisconsin in Madison. Seven days later, Purdue inaugurated racing on the Wabash River when it beat Lane Technical High School, sponsored by Chicago’s Lincoln Park Boat Club. According to the Exponent, the race signified “the introduction of the sport in this section of the country.” (Today, because of the unpredictable water levels of the Wabash, Purdue hosts races at Eagle Creek Park in Indianapolis.)

The next year, Purdue won its first trophy in a race hosted on the Wabash against the Detroit Boat Club, the oldest rowing club in the United States. In 1958, the crew purchased its first new shell, then made of wood and called a Pocock after George Yeoman Pocock, leading designer of racing shells in the 20th century. Shells—often named after an advisor, alum, or coach—were later made of fiberglass and are now made of carbon fiber.

In 1959, ROTC signalmen set up a wireless system for an announcer to give the first race broadcast with walkie-talkie commentary through loudspeakers that were mounted on the Boilermaker Special, which was parked at the finish. For the first time, spectators on shore could hear announcements of the race progression.

Purdue crew’s love for the unforgiving took root 75 years ago.

The team was founded by Cuban-born brothers Ken (S’53) and Bill (ECE’51) Butler, rowers who were distant cousins of Winthrop Stone, Purdue’s president from 1900 to 1921.

In the summer of 1949, Ken rowed for the undefeated Havana Biltmore program. That fall, he came to Purdue, joining his brother who was already a student. Ken longed to continue rowing, and the Wabash River beckoned.

In early 1950, Bill, spurred by Ken, placed a series of letters in the Purdue Exponent titled “The Sport of Rowing.” As intended, the letters enticed students’ interest. A meeting was held in the Purdue Memorial Union to organize a rowing team.

When the University of Wisconsin heard that Purdue wanted to start a crew but could not afford a boat, they donated their mothballed, eight-oared, canvas-covered shell. Nearly rotted, it became Purdue Crew’s pride and joy.

M.L. Clevett, head of Purdue’s Intramural Department, facilitated the club’s formation, locating land loaned by the Lincoln Lodge (later renamed Merou Grotto and demolished in 2019) on North River Road for the team to build a dock and boathouse. Over the years, Crew received steadfast support from Purdue’s Recreational Sports Division, now known as Recreation & Wellness.

The seven-member club formulated a constitution, and rowing machines were set up at Lambert Fieldhouse. Norwegian student Hakon Refsum (ME’52) was the first official coach.

Purdue’s inaugural race occurred on June 2, 1951, at the Culver Military Academy with Ken Butler as coxswain.

The Exponent reported, “The race was close at halfway, with Purdue up by a bow length. Disaster struck Purdue when the crews hit rough water caused by a patch of unprotected wind. Rowing errors ensued, described as ‘catching crabs,’ and Culver pulled ahead in the choppy water for the win.”

The following year, Purdue received a used cedar shell from Harvard, procured by history professor Robert B. Eckles, a Harvard graduate and the team’s first faculty advisor. With two boats, the members could arrange their first racing schedule. In his book Purdue Crew—20 Years of Rowing: 1949–1969, former coxswain Bruce Blackwell (M’64) recalled that the good-natured Eckles made the team feel important. Yet, “the school and its body barely knew we were on the river.”

The first crew race between Big Ten schools (and the only Big Ten rowing teams at the time) occurred on May 3, 1952, when Purdue rowed unsuccessfully against Wisconsin in Madison. Seven days later, Purdue inaugurated racing on the Wabash River when it beat Lane Technical High School, sponsored by Chicago’s Lincoln Park Boat Club. According to the Exponent, the race signified “the introduction of the sport in this section of the country.” (Today, because of the unpredictable water levels of the Wabash, Purdue hosts races at Eagle Creek Park in Indianapolis.)

The next year, Purdue won its first trophy in a race hosted on the Wabash against the Detroit Boat Club, the oldest rowing club in the United States. In 1958, the crew purchased its first new shell, then made of wood and called a Pocock after George Yeoman Pocock, leading designer of racing shells in the 20th century. Shells—often named after an advisor, alum, or coach—were later made of fiberglass and are now made of carbon fiber.

In 1959, ROTC signalmen set up a wireless system for an announcer to give the first race broadcast with walkie-talkie commentary through loudspeakers that were mounted on the Boilermaker Special, which was parked at the finish. For the first time, spectators on shore could hear announcements of the race progression.

Fifteen years later, with Title IX, women would begin rowing for Purdue.

In 1974, during a men’s team meeting, several women showed up at the boathouse in cut-off shorts and flannel shirts and announced they wanted to row. There was no formal rowing gear at the time, and women’s athletic wear would not materialize until the next decade. Team captain Kevin Sauer (M’76) told them practice was at 5:30 the next morning.

“They showed up,” Sauer said in 2020. “And they kept showing up. After a few weeks, I knew they were real. What was happening [with women’s sports] around the country was real.”

With a few tweaks to the riggers, the women adapted the shells built for men, and Sauer became the women’s coach.

On September 30, 1980, a tiny classified ad ran in the Exponent that read, “PURDUE WOMEN! Are you looking for relief from studies? Work your tensions away by joining a unique sport! Purdue’s Women’s Rowing Club.” That year, Sue Pleiss (CE’80), club president, was the first woman to win the prestigious Hovde Award.

Fifteen years later, with Title IX, women would begin rowing for Purdue.

In 1974, during a men’s team meeting, several women showed up at the boathouse in cut-off shorts and flannel shirts and announced they wanted to row. There was no formal rowing gear at the time, and women’s athletic wear would not materialize until the next decade. Team captain Kevin Sauer (M’76) told them practice was at 5:30 the next morning.

“They showed up,” Sauer said in 2020. “And they kept showing up. After a few weeks, I knew they were real. What was happening [with women’s sports] around the country was real.”

With a few tweaks to the riggers, the women adapted the shells built for men, and Sauer became the women’s coach.

On September 30, 1980, a tiny classified ad ran in the Exponent that read, “PURDUE WOMEN! Are you looking for relief from studies? Work your tensions away by joining a unique sport! Purdue’s Women’s Rowing Club.” That year, Sue Pleiss (CE’80), club president, was the first woman to win the prestigious Hovde Award.

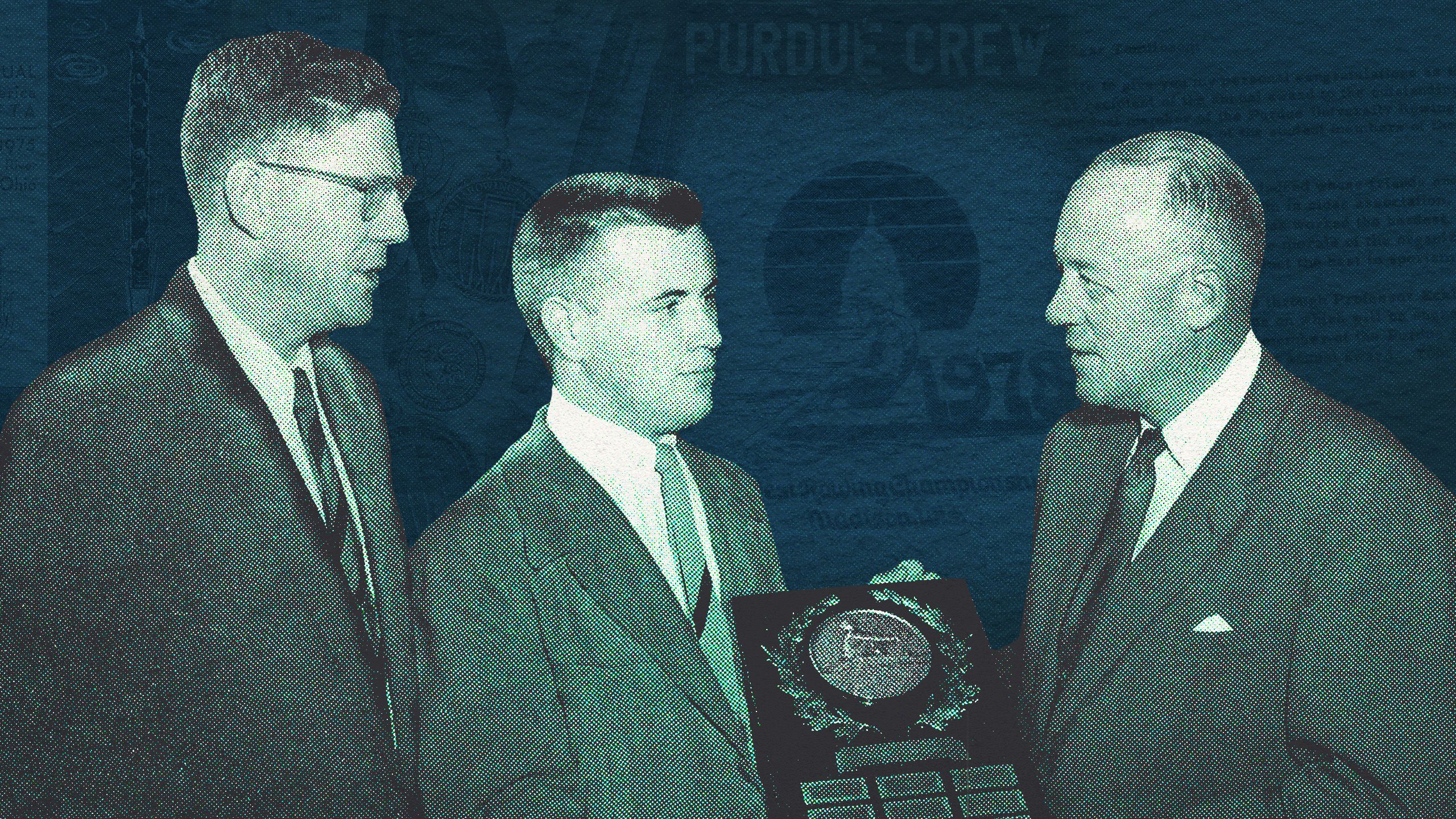

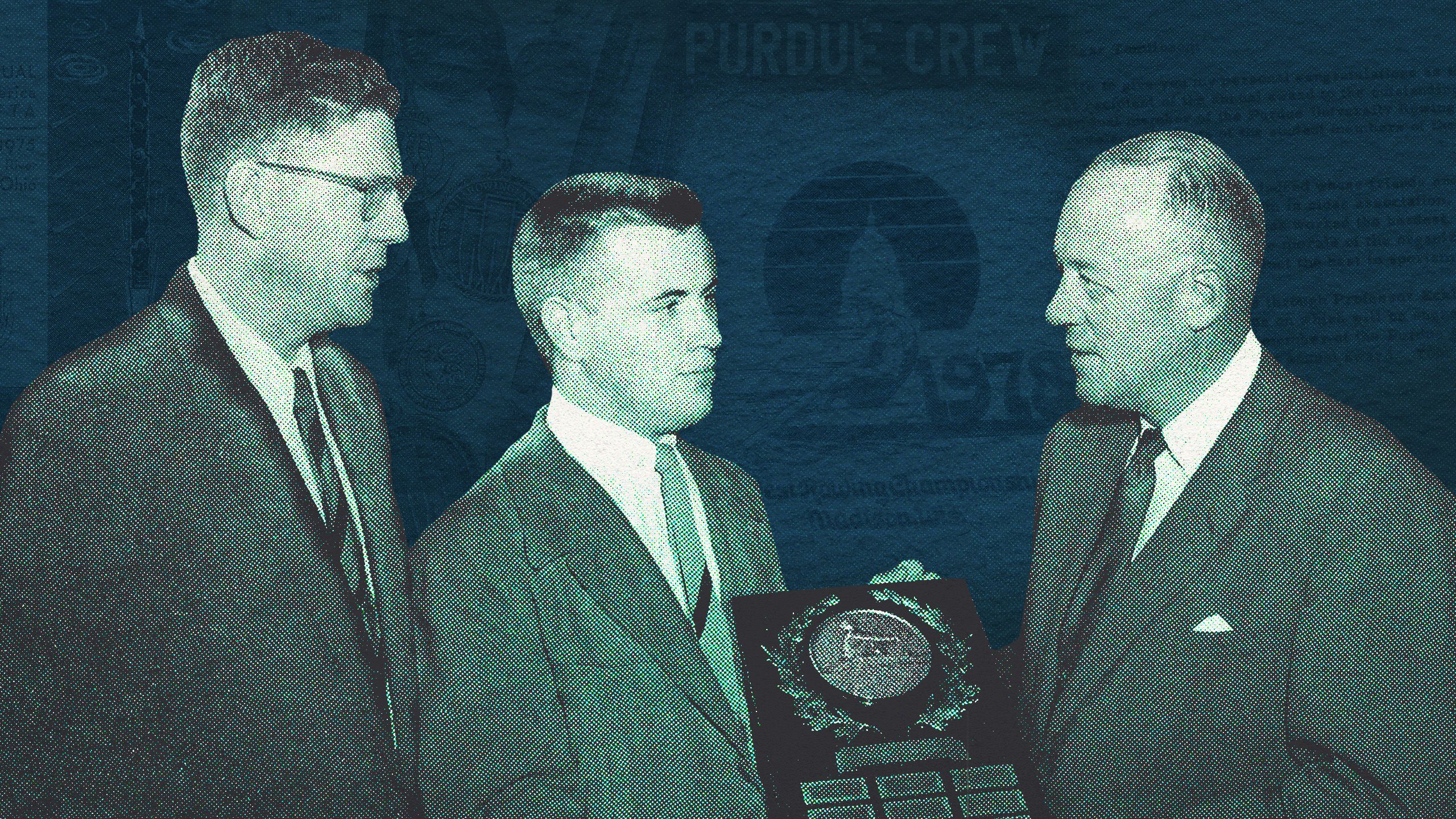

Purdue President Frederick L. Hovde (HDR E’75) initiated an honorary crew award in his name in the spring of 1955. A Rhodes Scholar who played rugby at Oxford University, Hovde never rowed but became acquainted with the sport’s popularity in England and said he wished he had rowed while at Oxford. The Hovde Award is presented annually by the president of the university to a student demonstrating “loyal, conscientious, and dedicated service” to Purdue Crew.

Purdue President Frederick L. Hovde (HDR E’75) initiated an honorary crew award in his name in the spring of 1955. A Rhodes Scholar who played rugby at Oxford University, Hovde never rowed but became acquainted with the sport’s popularity in England and said he wished he had rowed while at Oxford. The Hovde Award is presented annually by the president of the university to a student demonstrating “loyal, conscientious, and dedicated service” to Purdue Crew.

Ellen Shew Holland, who rowed and coached in the 1980s, is the president of the Purdue Rowing Association (PRA), the alumni organization that advocates and leads fundraising efforts for Purdue Crew.

“When I saw the crew, I was drawn to the beauty and the strength,” Shew Holland says. “It was like a ballet.”

Her older brother, Ed Shew (ABE’77), had previously rowed and was her first coach. According to Shew Holland, rowing is a tradition in many Purdue families, perpetuating a legacy of grit, perfection, success, and teamwork on the water.

The importance of teamwork was underscored in 1982, when the women had an opportunity to become a varsity sport—meaning the men’s and women’s teams would have separated and had access to different resources.

“I distinctly remember Coach Sauer holding a team meeting in the boathouse,” Shew Holland recalls. “We had the chance to take advantage of Title IX, which would include funding for a coach and equipment. We all voted that we stay as one group.”

Nearly 40 years after the first women joined Purdue Crew, West Lafayette native Amanda Elmore (S’13) became the first Purdue alumna to win an Olympic gold medal when she stroked for the U.S. women’s eight rowing team in Rio de Janeiro in 2016.

Ellen Shew Holland, who rowed and coached in the 1980s, is the president of the Purdue Rowing Association (PRA), the alumni organization that advocates and leads fundraising efforts for Purdue Crew.

“When I saw the crew, I was drawn to the beauty and the strength,” Shew Holland says. “It was like a ballet.”

Her older brother, Ed Shew (ABE’77), had previously rowed and was her first coach. According to Shew Holland, rowing is a tradition in many Purdue families, perpetuating a legacy of grit, perfection, success, and teamwork on the water.

The importance of teamwork was underscored in 1982, when the women had an opportunity to become a varsity sport—meaning the men’s and women’s teams would have separated and had access to different resources.

“I distinctly remember Coach Sauer holding a team meeting in the boathouse,” Shew Holland recalls. “We had the chance to take advantage of Title IX, which would include funding for a coach and equipment. We all voted that we stay as one group.”

Nearly 40 years after the first women joined Purdue Crew, West Lafayette native Amanda Elmore (S’13) became the first Purdue alumna to win an Olympic gold medal when she stroked for the U.S. women’s eight rowing team in Rio de Janeiro in 2016.

Build it, and they will row.

Sauer and other alumni helped Crew move its headquarters from North River Road to South River Road in 1979.

The boathouse—a pole barn with dirt floors—was located near Fort Ouiatenon, but the team’s workout facilities were still in the basement of Lambert Fieldhouse.

In 2010, after 10 years of planning and fundraising, a new two-story boathouse was built along the Wabash River not far from Tapawingo Park at a cost of $1.6 million. Purdue alumni raised all but $300,000. It is the crew’s first boathouse with heat and running water, but, in a nod to the past, there are no showers.

In the spacious boathouse, students train surrounded by history. Purdue Crew cofounder Bill Butler, who died in June, spearheaded the creation of “Bill’s Dream Wall” in 2019. The mural, depicting seven decades of struggle and success, runs the length of the boathouse. Banners, silver trophies, vintage photos, retired oars, and shells frame the team as they build muscle and endurance.

In the 1990s, Bill created Crew’s first endowment—the Kenneth M. Butler Memorial Fund—to honor his brother who died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1962. The team has set a goal to raise $15 million and become fully endowed so students pay a nominal fee and costs do not prevent anyone from rowing. In 2023, Crew initiated a weeklong summer camp for high schoolers as an annual fundraiser and recruitment tool.

A Crew mantra is “Pulling for each other while pulling with each other.” Rowing thrives on a synergy of effort—a shared purpose that transcends individual achievements.

“If you can feel your legs that last 500 meters, you’re not rowing hard enough,” Shew Holland says. “You’re focused on that stroke, and you’re pounding and pounding. When you’re in sync, it’s called swinging. Lifting the boat, gliding on the water. It’s trust, confidence, and belief in your teammates and in yourself. Together, we can lift the boat.”

Build it, and they will row.

Sauer and other alumni helped Crew move its headquarters from North River Road to South River Road in 1979.

The boathouse—a pole barn with dirt floors—was located near Fort Ouiatenon, but the team’s workout facilities were still in the basement of Lambert Fieldhouse.

In 2010, after 10 years of planning and fundraising, a new two-story boathouse was built along the Wabash River not far from Tapawingo Park at a cost of $1.6 million. Purdue alumni raised all but $300,000. It is the crew’s first boathouse with heat and running water, but, in a nod to the past, there are no showers.

In the spacious boathouse, students train surrounded by history. Purdue Crew cofounder Bill Butler, who died in June, spearheaded the creation of “Bill’s Dream Wall” in 2019. The mural, depicting seven decades of struggle and success, runs the length of the boathouse. Banners, silver trophies, vintage photos, retired oars, and shells frame the team as they build muscle and endurance.

In the 1990s, Bill created Crew’s first endowment—the Kenneth M. Butler Memorial Fund—to honor his brother who died of a cerebral hemorrhage in 1962. The team has set a goal to raise $15 million and become fully endowed so students pay a nominal fee and costs do not prevent anyone from rowing. In 2023, Crew initiated a weeklong summer camp for high schoolers as an annual fundraiser and recruitment tool.

A Crew mantra is “Pulling for each other while pulling with each other.” Rowing thrives on a synergy of effort—a shared purpose that transcends individual achievements.

“If you can feel your legs that last 500 meters, you’re not rowing hard enough,” Shew Holland says. “You’re focused on that stroke, and you’re pounding and pounding. When you’re in sync, it’s called swinging. Lifting the boat, gliding on the water. It’s trust, confidence, and belief in your teammates and in yourself. Together, we can lift the boat.”

PULL FOR THE TEAM

Make a gift to help fund Purdue Crew’s endowment today!

Learn more about Purdue Crew on the team’s website.

Read more stories from this issue of Purdue Alumnus magazine.