Answering the Call

// By Aaron Martin (LA’94)

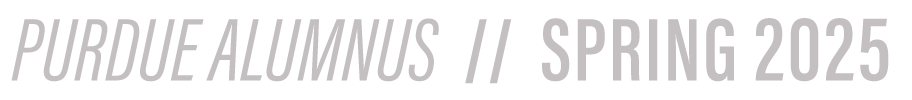

// Illustrations by Matt Chinworth

Grief does not follow a set course. It can linger, reshape, and sometimes mobilize a collective response.

For many Americans who witnessed the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, sorrow was met with purpose—with resolve, service, and unity.

Tens of thousands enlisted in the military in the wake of the attacks. Many others joined the emergency services as police officers and firefighters, and millions more donated to charitable organizations supporting relief and recovery efforts. American flags were flown on porches from coast to coast.

Grief does not follow a set course. It can linger, reshape, and sometimes mobilize a collective response.

For many Americans who witnessed the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, sorrow was met with purpose—with resolve, service, and unity.

Tens of thousands enlisted in the military in the wake of the attacks. Many others joined the emergency services as police officers and firefighters, and millions more donated to charitable organizations supporting relief and recovery efforts. American flags were flown on porches from coast to coast.

Amid this swell of patriotism and caring, Liz White knew she could answer the call in her own way—and make an immediate impact.

For White (EDU’74), a psychologist and crisis counselor, the initial shock of 9/11 quickly became an urgent mission—a deep desire to help mend the psychological and emotional damage that was left behind. A volunteer for the American Red Cross, she found herself working at Ground Zero within days of the attacks.

In the four months following 9/11, White spent seven weeks as an on-site psychologist. In the decades since, she has volunteered at disaster sites around the country while maintaining a private practice in Virginia. She will retire in December 2025.

“September 11 happened not three weeks after I joined the Red Cross, and I remember thinking, I’ve got to go there—that this would be a defining moment in my life,” says White, who was presented with the President’s Volunteer Service Award by President Barack Obama for amassing more than 14,000 hours of volunteer service.

“There is certainly a psychological cost to what I do, yet I am very grateful to have served,” White says. “I’ve learned a lot about grief in my career, and that took on a whole new level of meaning when I joined the Red Cross and began volunteering at Ground Zero. The sadness was just so overwhelming. But it was also one of those times when people—strangers—came together effortlessly to begin the work of recovery. There was a profound feeling of offering ourselves to this critical moment of history, and it was a uniting event—very powerful.”

Amid this swell of patriotism and caring, Liz White knew she could answer the call in her own way—and make an immediate impact.

For White (EDU’74), a psychologist and crisis counselor, the initial shock of 9/11 quickly became an urgent mission—a deep desire to help mend the psychological and emotional damage that was left behind. A volunteer for the American Red Cross, she found herself working at Ground Zero within days of the attacks.

In the four months following 9/11, White spent seven weeks as an on-site psychologist. In the decades since, she has volunteered at disaster sites around the country while maintaining a private practice in Virginia. She will retire in December 2025.

“September 11 happened not three weeks after I joined the Red Cross, and I remember thinking, I’ve got to go there—that this would be a defining moment in my life,” says White, who was presented with the President’s Volunteer Service Award by President Barack Obama for amassing more than 14,000 hours of volunteer service.

“There is certainly a psychological cost to what I do, yet I am very grateful to have served,” White says. “I’ve learned a lot about grief in my career, and that took on a whole new level of meaning when I joined the Red Cross and began volunteering at Ground Zero. The sadness was just so overwhelming. But it was also one of those times when people—strangers—came together effortlessly to begin the work of recovery. There was a profound feeling of offering ourselves to this critical moment of history, and it was a uniting event—very powerful.”

White spent 25 years as a social worker and trauma specialist—including more than 10 years leading a team of eight psychologists in her own private practice—before she decided to go part time and volunteer her services to a major relief organization. She had enjoyed reading the biography of Red Cross founder Clara Barton as a child and wound up joining the organization.

The Red Cross stationed White in Philadelphia, less than 100 miles from New York City.

“I always wanted to take the more difficult cases in my private practice—people who had death or tragic losses in their lives—because I believe we should never feel like we’re alone in those moments,” White says. “After years of private practice, having dealt with a number of those critical cases, I figured out that I wanted to be where loss occurred in the greater world. I just felt like I had more to give.”

Exactly 14 days after the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers, White and a team of Red Cross colleagues took a train from Philadelphia into the heart of New York City.

White has vivid memories of the first time she saw Ground Zero.

I walked in down a perimeter street, and it was very dark because the electricity was out, but I remember seeing the glow of the big lights—they had brought in stadium lights so everyone could see—and it was just a huge pile at that point.

I was stunned and mortified by the devastation. It was a horrendous site to walk—it was a war zone, with dust and debris everywhere—and I remember how all the workers did their jobs in total silence. There weren’t words to say at that time—it was beyond words. Everybody knew we were on sacred ground.

In the weeks to come, White’s primary duty was to provide emotional support along with another psychologist and occasionally a pastor. They counseled first responders and emergency personnel involved in search and recovery, construction workers tasked with debris removal, witnesses to the attack, bystanders—anyone who needed help.

“Every once in a while, someone would find a helmet in the debris, and everything would just stop—what can you say to that person?” White says. “Many of the people there weren’t trained for that kind of work, and they would get this stare of sadness and disbelief—it was totally foreign to them, and it was just too much. But everyone found a way to keep doing their jobs, diligently, which is remarkable. They just focused as best they could, which is what I did—I didn’t give myself the time to cry about it until two weeks later, on a break back in Philadelphia.”

As efforts continued at Ground Zero, holiday season came and went, and mental and physical exhaustion set in for many of the on-site personnel. During this time, it was often small acts of kindness that got them through.

For White, one such example was when a longtime friend who teaches first grade had her students send personal notes and drawings to the workers.

“We were so isolated and immersed in what we were doing—there was obviously no holiday spirit—so any joy came in little moments,” White says. “One thing I remember being touched by was when the workers got cards and drawings from those kids and put them under their helmets or hid them under their hats. Those little drawings, as simple as they were, gave them faith or the feeling that the world cared. Because in the space of Ground Zero, there was no sense of the togetherness felt by the nation or the world. We needed that reminder.”

Although it might have seemed like an odd decision to many, White volunteered for the night shift throughout her time at Ground Zero. She came to prefer working nights, and that experience provided one of her enduring memories.

“There was something about the glow of the lights in the night that I will never forget,” she says. “You really got the feeling of a higher power—the goodness that overpowers evil.”

White spent 25 years as a social worker and trauma specialist—including more than 10 years leading a team of eight psychologists in her own private practice—before she decided to go part time and volunteer her services to a major relief organization. She had enjoyed reading the biography of Red Cross founder Clara Barton as a child and wound up joining the organization.

The Red Cross stationed White in Philadelphia, less than 100 miles from New York City.

“I always wanted to take the more difficult cases in my private practice—people who had death or tragic losses in their lives—because I believe we should never feel like we’re alone in those moments,” White says. “After years of private practice, having dealt with a number of those critical cases, I figured out that I wanted to be where loss occurred in the greater world. I just felt like I had more to give.”

Exactly 14 days after the terrorist attacks on the Twin Towers, White and a team of Red Cross colleagues took a train from Philadelphia into the heart of New York City.

White has vivid memories of the first time she saw Ground Zero.

I walked in down a perimeter street, and it was very dark because the electricity was out, but I remember seeing the glow of the big lights—they had brought in stadium lights so everyone could see—and it was just a huge pile at that point.

I was stunned and mortified by the devastation. It was a horrendous site to walk—it was a war zone, with dust and debris everywhere—and I remember how all the workers did their jobs in total silence. There weren’t words to say at that time—it was beyond words. Everybody knew we were on sacred ground.

In the weeks to come, White’s primary duty was to provide emotional support along with another psychologist and occasionally a pastor. They counseled first responders and emergency personnel involved in search and recovery, construction workers tasked with debris removal, witnesses to the attack, bystanders—anyone who needed help.

“Every once in a while, someone would find a helmet in the debris, and everything would just stop—what can you say to that person?” White says. “Many of the people there weren’t trained for that kind of work, and they would get this stare of sadness and disbelief—it was totally foreign to them, and it was just too much. But everyone found a way to keep doing their jobs, diligently, which is remarkable. They just focused as best they could, which is what I did—I didn’t give myself the time to cry about it until two weeks later, on a break back in Philadelphia.”

As efforts continued at Ground Zero, holiday season came and went, and mental and physical exhaustion set in for many of the on-site personnel. During this time, it was often small acts of kindness that got them through.

For White, one such example was when a longtime friend who teaches first grade had her students send personal notes and drawings to the workers.

“We were so isolated and immersed in what we were doing—there was obviously no holiday spirit—so any joy came in little moments,” White says. “One thing I remember being touched by was when the workers got cards and drawings from those kids and put them under their helmets or hid them under their hats. Those little drawings, as simple as they were, gave them faith or the feeling that the world cared. Because in the space of Ground Zero, there was no sense of the togetherness felt by the nation or the world. We needed that reminder.”

Although it might have seemed like an odd decision to many, White volunteered for the night shift throughout her time at Ground Zero. She came to prefer working nights, and that experience provided one of her enduring memories.

“There was something about the glow of the lights in the night that I will never forget,” she says. “You really got the feeling of a higher power—the goodness that overpowers evil.”

Even though she didn’t fully realize it at the time, White’s interest in understanding and treating grief began to crystallize during one particularly tumultuous year early in her life.

It was 1968, White’s junior year in high school. Her family, who had called Kokomo, Indiana, home throughout her early youth, was forced to relocate to a rural farm outside the city due to financial difficulties. It was also a time of societal strife in America—unrest over the conflict in Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy made it seem as if the world was tearing itself apart.

Things only got worse for White after the move. She suffered a broken leg, complicating her adjustment to a new school, and her grandfather died. Most traumatic of all were two tragic horse-riding accidents that she and her mom witnessed on her family’s farm.

“Because there was so much turmoil, it was a time in my life where I felt like death and sadness were just all around me,” White says. “I went silent for a long time because I just didn’t want to talk about all the grief and loss—and I certainly didn’t want to add to my mom’s grief. I didn’t talk about that horrific year for a long time.”

Instead, White retreated into academics, which “seemed like a place you could go to find peace and gain some control.”

With strong family ties to Purdue, including a grandmother who graduated in 1944 and served as a lifelong inspiration, White was always determined to attend the university. A full scholarship made this possible, and she fit in immediately.

“Purdue did a wonderful job of making campus feel like home,” says White, who most recently returned to campus for Homecoming 2024 and the Class of 1974’s 50th reunion. “There was a real feeling of harmony and authenticity, which was meaningful to me.”

By this time, White was interested in exploring psychology as a career—yet she ended up majoring in elementary education. White credits one of her first professors for steering her along this indirect path to her goal.

“That professor was wonderful because she told me that the best way to know people is to understand children first, and the only way Purdue offers those experiences with children is through elementary education,” White says. “I knew I didn’t want to be a teacher—I wanted to be a teacher of life—and that was some of the best advice I’ve ever received. It was a critical change in how I approached my growth.”

Even though she didn’t fully realize it at the time, White’s interest in understanding and treating grief began to crystallize during one particularly tumultuous year early in her life.

It was 1968, White’s junior year in high school. Her family, who had called Kokomo, Indiana, home throughout her early youth, was forced to relocate to a rural farm outside the city due to financial difficulties. It was also a time of societal strife in America—unrest over the conflict in Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, and the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy made it seem as if the world was tearing itself apart.

Things only got worse for White after the move. She suffered a broken leg, complicating her adjustment to a new school, and her grandfather died. Most traumatic of all were two tragic horse-riding accidents that she and her mom witnessed on her family’s farm.

“Because there was so much turmoil, it was a time in my life where I felt like death and sadness were just all around me,” White says. “I went silent for a long time because I just didn’t want to talk about all the grief and loss—and I certainly didn’t want to add to my mom’s grief. I didn’t talk about that horrific year for a long time.”

Instead, White retreated into academics, which “seemed like a place you could go to find peace and gain some control.”

With strong family ties to Purdue, including a grandmother who graduated in 1944 and served as a lifelong inspiration, White was always determined to attend the university. A full scholarship made this possible, and she fit in immediately.

“Purdue did a wonderful job of making campus feel like home,” says White, who most recently returned to campus for Homecoming 2024 and the Class of 1974’s 50th reunion. “There was a real feeling of harmony and authenticity, which was meaningful to me.”

By this time, White was interested in exploring psychology as a career—yet she ended up majoring in elementary education. White credits one of her first professors for steering her along this indirect path to her goal.

“That professor was wonderful because she told me that the best way to know people is to understand children first, and the only way Purdue offers those experiences with children is through elementary education,” White says. “I knew I didn’t want to be a teacher—I wanted to be a teacher of life—and that was some of the best advice I’ve ever received. It was a critical change in how I approached my growth.”

After graduation, White earned a master’s degree in clinical social work from Washington University in St. Louis and then spent more than a decade honing her skills at various mental-health centers. She opened her private practice in 1988 and spent years focusing on that—until she had an epiphany.

“I was at a stage in my life where I was looking for more meaning,” White says. “I knew I was equipped to do more, so I started looking at ways to make that happen.”

It was a pivotal decision, as White was swept from the comfort of her everyday office to the Red Cross to Ground Zero following the attacks on 9/11—her first major disaster and one of the most emotionally devastating catastrophes in American history.

“Everybody sees these disasters unfold on television, and that’s a traumatic experience in itself, but that can never give you a full understanding of the level of devastation these events bring with them,” says White, who earned a doctoral certificate for crisis intervention from the University of South Dakota in 2005.

“In every case, you’re dealing with tremendous tragedy and loss,” she says. “In the cases where there is evacuation, there’s a sense of abandonment—people are often leaving their homes and even their animals behind forever—and a tremendous fear about what’s next. Lives are changed forever.”

As she approaches retirement, White is content knowing that she will never leave her memories and experiences behind.

“I’m just older now, and it’s time, but my heart will always be there with the people who suffer,” she says. “Beginning with 9/11, I’ve learned to live a far, far more meaningful life. I’ve learned a lot about grief and being present and listening. Grief is about love and loss and what you do with it. It’s hard to know what to do with your grief, but I think it’s about keeping yourself close to the meaning of those people who are no longer here—and living in the goodness of them.”

After graduation, White earned a master’s degree in clinical social work from Washington University in St. Louis and then spent more than a decade honing her skills at various mental-health centers. She opened her private practice in 1988 and spent years focusing on that—until she had an epiphany.

“I was at a stage in my life where I was looking for more meaning,” White says. “I knew I was equipped to do more, so I started looking at ways to make that happen.”

It was a pivotal decision, as White was swept from the comfort of her everyday office to the Red Cross to Ground Zero following the attacks on 9/11—her first major disaster and one of the most emotionally devastating catastrophes in American history.

“Everybody sees these disasters unfold on television, and that’s a traumatic experience in itself, but that can never give you a full understanding of the level of devastation these events bring with them,” says White, who earned a doctoral certificate for crisis intervention from the University of South Dakota in 2005.

“In every case, you’re dealing with tremendous tragedy and loss,” she says. “In the cases where there is evacuation, there’s a sense of abandonment—people are often leaving their homes and even their animals behind forever—and a tremendous fear about what’s next. Lives are changed forever.”

As she approaches retirement, White is content knowing that she will never leave her memories and experiences behind.

“I’m just older now, and it’s time, but my heart will always be there with the people who suffer,” she says. “Beginning with 9/11, I’ve learned to live a far, far more meaningful life. I’ve learned a lot about grief and being present and listening. Grief is about love and loss and what you do with it. It’s hard to know what to do with your grief, but I think it’s about keeping yourself close to the meaning of those people who are no longer here—and living in the goodness of them.”